Llisa Draws a Letter

Llisa Demetrios goes behind the scenes to recount how her childhood memories of Ray and Charles come full circle in her new role as chief curator.

A portrait of the author and Eames Institute chief curator, Llisa Demetrios, taken by Charles Eames in July 1972. © Eames Office LLC

One of my favorite memories of being with my grandparents also happens to be on film. In the mid-1970s—when I must have been around ten years old—they set me up on the floor of their living room with pads of colorful paper, pens, pencils, glue, and scissors. Ray and Charles asked me to create whatever I wanted while they filmed me with one of the first Polavision cameras—a new technology sent to them by Edwin Land, the cofounder of Polaroid.

As the filming started, I remember feeling the scratchy wool rug on the backs of my legs and awkwardly shifting positions to avoid contact with it. Nonetheless it was calm and quiet as the sunlight streamed through the eucalyptus trees into their iconic living room—now a jumble of art supplies. Over the next hour I drew, cut, colored, and glued together something not unlike a valentine as my grandparents and a small group of colleagues observed and filmed me, occasionally asking me to move or pause.

The next time we went to Los Angeles, my mother, Lucia, and I gathered in the living room of the house. Charles pulled down a screen at the western end of the space and darkened the room. Near the seating alcove, Ray opened a cabinet door to reveal a film projector inside. “We have a surprise for you, Llisa,” she said. Moments later there I was on the screen crafting the heart I had made there just a few weeks earlier. The experience was almost surreal—watching a memory of myself in the space within the space itself.

All these years later, that memory within a memory isn’t any less special, but it is perhaps more typical of how I have since come to experience my grandparents’ legacy—as layers upon layers that continually unfold, diverge, circle back, and eventually reveal an ever-expanding network of connections.

Stills from a film featuring Llisa Demetrios creating art in the Eames House, part of a series made in 1977 to promote the Polavision camera. © Eames Office LLC

As a kid it really didn’t seem unusual to me that a film my grandparents made would be shown at my school. Like a lot of people, I remember watching The Powers of Ten in my 10th grade science classroom. But unlike a lot of people, I also have a vivid memory of arriving at my grandparents’ studio at 901 Washington in Venice, California, to find Charles balancing a film camera atop a cherry picker thirty feet up in the air while a man and a woman lay on a picnic blanket on the grass below. Ray orbited the scene taking photographs with her 35mm camera, while a team from the office helped produce the technically demanding zoom effect by calibrating the movement of the cherry picker with the zoom of the lens.

Even now, I’m struck by the thought that a normal day for Ray and Charles entailed this kind of wizardry. Seeing the finished project was a revelation, not just because the film gave me a whole new perspective on scale, but because I also gained an insight into the creative process—into all the work that goes on behind the scenes to seamlessly incorporate a few seconds of film into the film. As Charles was fond of saying, “the blood never shows.”

Llisa Demetrios tends to a gallery at the Eames Ranch, surrounded by designs and materials from the collection. / Photograph: Nicholas Calcott

My goal as the chief curator at the Eames Institute of Infinite Curiosity is to help recreate the world that existed outside of the frame. I am driven in this work to inspire others to learn from the way my grandparents approached their life and work so that they possibly might feel that sense of limitless potential that I got to experience firsthand and take it back and apply it in their own world. Ray and Charles didn’t believe in the notion of the gifted few—they believed that you got good at what you liked to do through practice, exploration, understanding, and effort.

When you start to color in the picture around the frame, you begin to feel that they approached life as one long learning opportunity—with each lesson building on the back of the one that came before. A glance at one of the many timelines or exhibitions they created should confirm that they were never intimidated by the prospect of information overload. Every interaction (or, indeed, everything) was an opportunity to learn something new, which would in turn lead to another thing, and another after that.

A photo of Charles Eames and Llisa Demetrios taken by Ray Eames in November 1976. © Eames Office LLC

Quite naturally, this curiosity was extended to me and my siblings as well. Ray and Charles would ask each of us what we were excited about and helped us discover and channel our interests. They ingrained in me that if I wanted to create a project, what was to stop me from doing so? When I was quite young, I built a little wood house for my Vitamin C capsules. Ray responded as though it was as serious and special as something an architect friend of hers might have created. We talked about why I’d designed the spaces as I had and how I might modify it in the future. We grandchildren never felt talked down to. They took us seriously, listened to us, and gave us advice to take into our own creative work. When I, at the age of 12, informed Charles that I wanted to be a sculptor, he told me, “You need to be able to use every tool in your studio as well if not better than the person you hire—or you won’t know if they are doing a good job.”

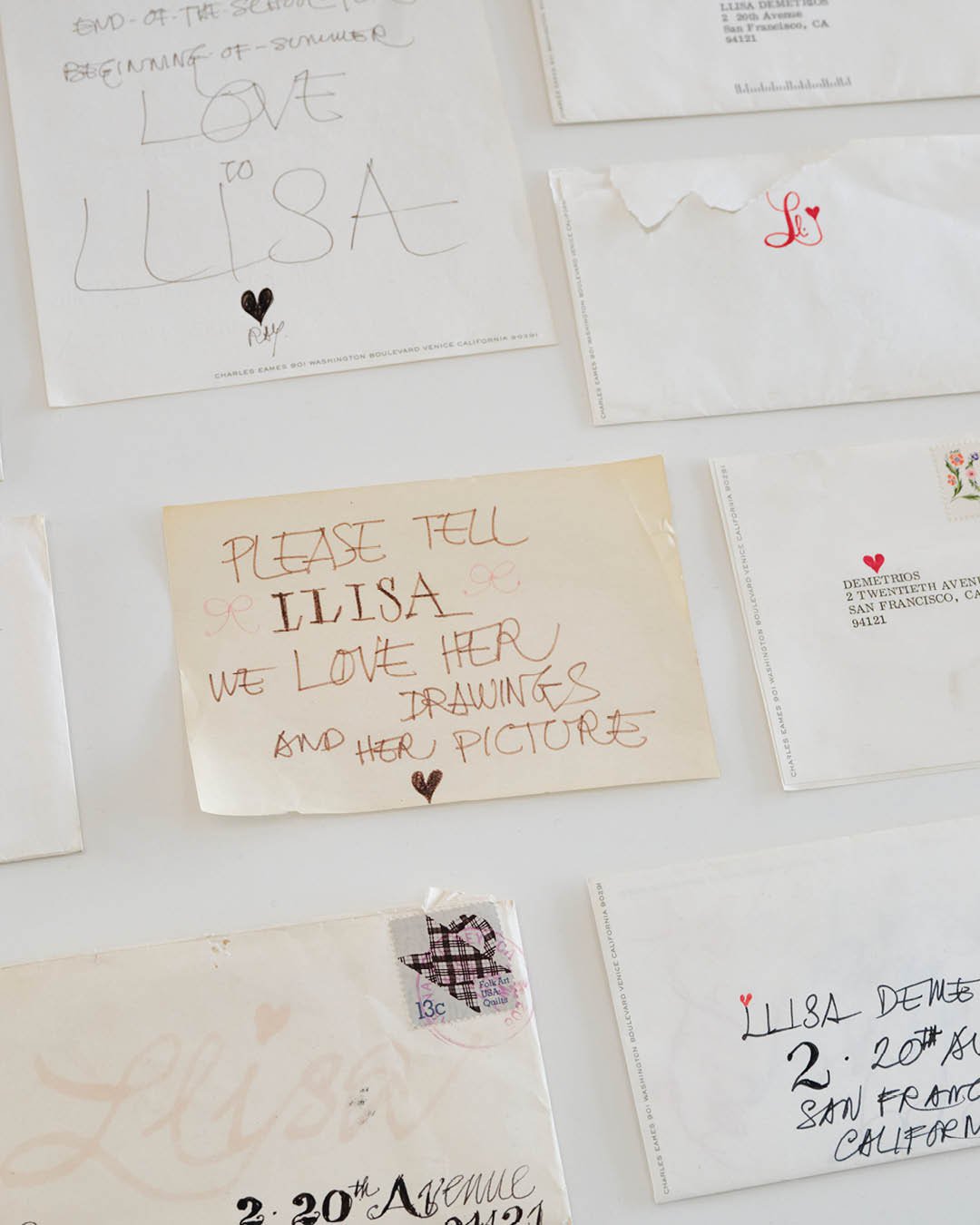

Selections of Ray and Charles’s personal notes and family correspondence from the Eames Collection. / Photographs: Nicholas Calcott

After Ray and Charles passed away, our family took on the responsibility of ensuring their legacy would be safeguarded. There were so many dimensions to Ray and Charles’s world, and so much material to process, that this work has been ongoing for decades distributed across multiple organizations on multiple continents. Even when the Library of Congress shipped all the office records, photographs, slides, and films off to Washington D.C., 901 barely looked like anything had been touched. After three years working at MoMA’s archives processing thousands of Mies van der Rohe drawings, I returned home to help my mom with the herculean task of getting our arms around what Ray and Charles left behind—a project I undertook as registrar of the Eames Office and that continues in my new role at the Eames Institute.

My mother always wanted to showcase what she felt was the most important part of Ray and Charles’s process—what she described as “how they got to the home run.” Archiving and documenting the hundreds of parts, molds, castings, and prototypes in the collection, or the drawing tools and papers from the graphics room drawers, or their books and magazines, may be painstaking, but my hope is that the result will allow for people to see that their genius maybe wasn’t genius after all, just a lot of hard work and dedication. Keeping the material together has also allowed a space for people to make their own conclusions and connections.

Lucia Eames outside of the Eames House in Los Angeles’s Pacific Palisades neighborhood, May 1972. © Eames Office LLC

As we prepare to make this material more available to the public, I often find myself thinking about my mom and seeing her vision for the property and the collection come to life in ways we never dreamed were possible. As we unpack crates and organize and house the material properly, I also find myself reliving those childhood memories with Ray and Charles—but through a different lens. When, as a child, I first saw Toccata for Toy Trains I wasn’t thinking about where those toys in the film came from or were stored. But now I find myself wondering what came first, the idea for the film, or the toy itself? Was the toy maybe a gift from a friend or someone they met in their travels? Where else does that same object show up again? What value, or values, did they see in it? What else were they doing at the same time? As I work through these layers (upon layers, upon layers), the picture outside the frame just gets richer and richer, and the lessons left behind clearer and clearer.

What’s most exciting to me is the fact that none of this is about looking backward. When we talk about preservation it implies that the thing being preserved is of value going forward. So what we’re doing here now is really all about the future. It’s about taking what Ray and Charles left us and building upon it for a better tomorrow—of looking at the problems we face in our world now and continuing to expand on that lifetime of learning. Ray and Charles had a profound effect on my life, and my greatest hope is that thanks to these efforts their impact will continue to resonate with curious problem-solvers for years to come. ❤

At Kazam! Magazine we believe design has the power to change the world. Our stories feature people, projects, and ideas that are shaping a better tomorrow.