An Eames of Your Own

Few designs have the longevity of Eames furniture, but buying vintage can be mystifying; our in-house expert explains what to look for—and what to avoid.

The timeless quality of Eames designs has made the work of Ray and Charles beloved not only among fans of mid-century modern furniture, but just about anyone who enjoys the beauty and usefulness of good design. Longtime and newly anointed Eames enthusiasts continually seek out vintage pieces, conscious that their patina tends to improve with age. However, the ardor for the Eameses’ craft often comes at a premium. Vintage Eames “Rope Edge” fiberglass chairs with their original bases regularly sell for more than triple the price of new fiberglass chairs. A storage cabinet purchased for $100 in 1950 sold for $48,000 in 2021; and an Organic Design Armchair and a DCW with experimental molded plywood arms each went for approximately $100,000 at auction. But it doesn’t take a fortune to collect vintage Eames furniture—through a combination of diligent research and informed knowledge, you can still find quality pieces at affordable prices.

So what should enthusiasts consider when they’ve decided to pursue an Eames classic? Daniel Ostroff, a longtime Eames devotee and head of acquisitions and research at the Eames Institute, has some answers to this question. In 1987, Ostroff bought an Eames desk and subsequently read “Connections,” Ralph Caplan’s seminal essay about the Eameses’ work. He became so enthralled by Ray and Charles’s design sensibility that he amassed not only a panoply of their furniture and designs but an encyclopedic understanding of their history and process—developed through conversations with collectors, museum curators, conservators, dealers, Eames Office alumni, and Eames family members.

Having something with honest patina is even better than having a piece in mint condition. There’s something about how things age that adds to their appeal.

Daniel Ostroff

Head of Acquisitions and Research

Eames Institute

Ostroff, a self-professed Eames aficionado, channeled his accumulated knowledge into writing and editing books like An Eames Anthology, as well as curating exhibitions of the duo’s designs. In this guide, he considers some starter tips for collecting the Eameses’ work, relevant for new and established collectors alike.

To provide context for any collecting endeavor, Ostroff recommends an evaluation system that encompasses four categories: Designer, Design, Technique, and Example. The first category refers to the designer of the piece; in this context, the Eameses, whose well-established reputation satisfies the initial criterion. “Design,” the next component of the four-part system, refers to the cachet of the specific piece: Is it one of the classic designs, like a chair from the Aluminum Group, or a less celebrated one? “Technique” refers to the manufacturing craft required for the piece: The Eameses used a variety of processes to create their furniture, ranging from plywood molding to upholstering fiberglass and beyond. The more techniques used, and the more complex the process used, the more valuable the item. For example, an original fiberglass chair with turned dowel wood legs is more highly prized than the same chair with bent steel legs. Collectors who understand that the upholstery on Eames shell chairs is handsewn often consider upholstered furniture to be of greater value. Finally, “Example” alludes to the qualities of the specific piece, its individual aesthetic appeal, and the history it embodies. Are all of the parts original to this specific example? The combination of these four assessments helps the collector to evaluate a potential piece’s value.

To help provide further context for assembling an Eames brood, Ostroff offers the following key points to consider when collecting.

Story over style

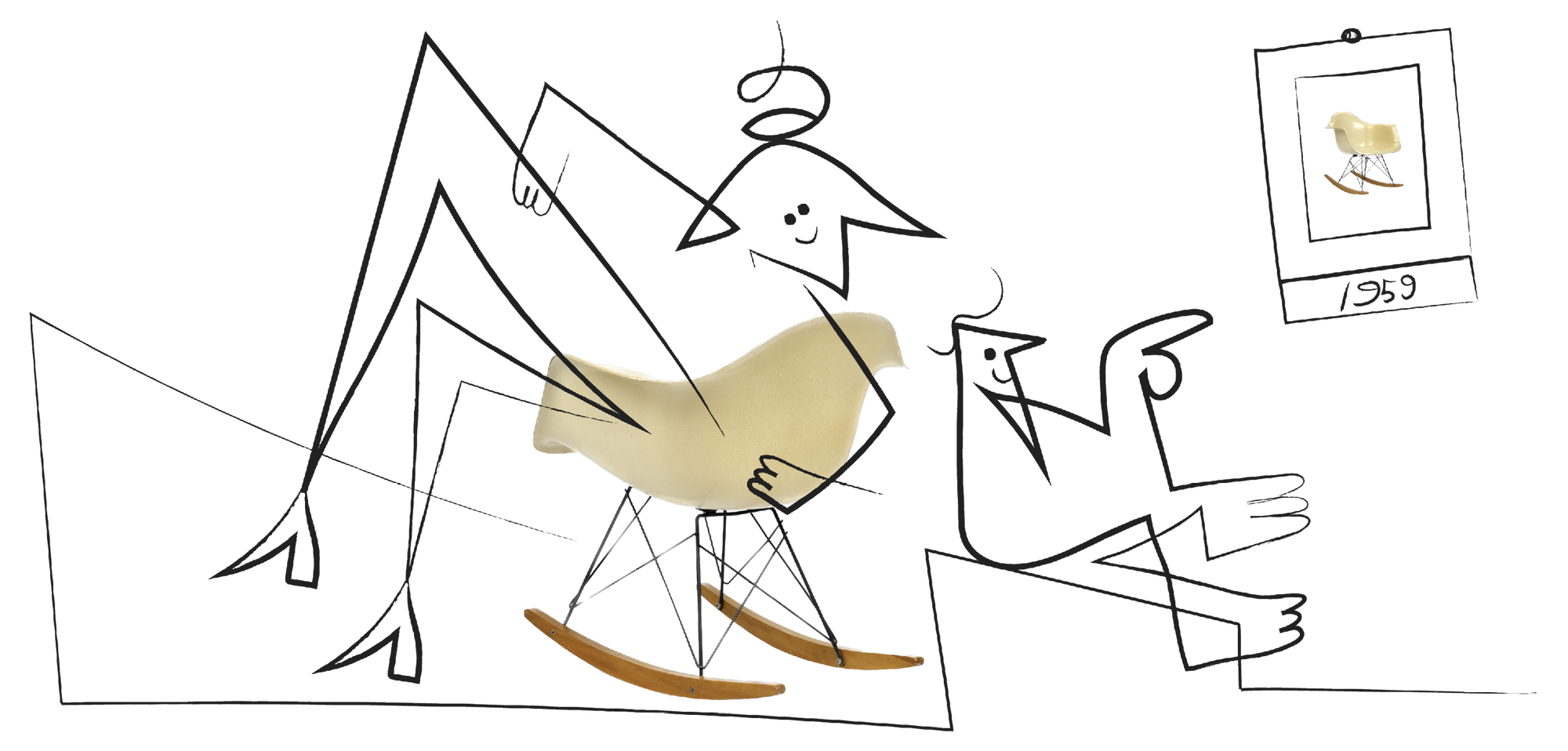

Ostroff: “When you’re considering a piece, try to find out as much about its history as you can. Who was the original owner? All Eames chairs were and still are made to order, and all had an original date of manufacture specific to that owner. Did the current owner refinish the piece? Do they have any documentation of the piece’s provenance? The best sellers will answer these questions, and a buyer who knows a chair’s history will have an enhanced appreciation of it. I once bought an Eames rocking chair from a seller who bought it in 1959, and she provided me with a photograph of her first child in the chair. I would rank a dateable 1959 rocking chair higher than one you buy from a dealer who won’t tell you where he got it, or doesn’t know the history.”

Don’t mess with patina

Ostroff: “I say ‘do no harm,’—meaning resist the urge to make any modifications to the piece. The less a collector does the better, especially if they have a piece in an original condition. Serious collectors want antiques that are as close as possible to the condition they were in when they left the hands of the maker, or the factory where the item was produced. Early on, I made a mistake when I bought an Eames desk. Over the objections of the longtime dealer, I had him re-chrome all the metal parts—and I was horrified when I saw the results. The top and panels of the desk had a wonderful patina, while the metal looked like it didn’t belong with the top. I now know that patina develops consistently, and once you start to clean or refresh a piece, you risk having something that looks like patchwork.

“Ray and Charles themselves anticipated the effect of age and wear on their designs, citing ‘how is it going to look in ten years?’ as one of their fundamental considerations. Having something with honest, original patina is in some ways even better than having a piece that’s in mint, factory-fresh condition, because there’s something about how things age that adds to their appeal and attractiveness.

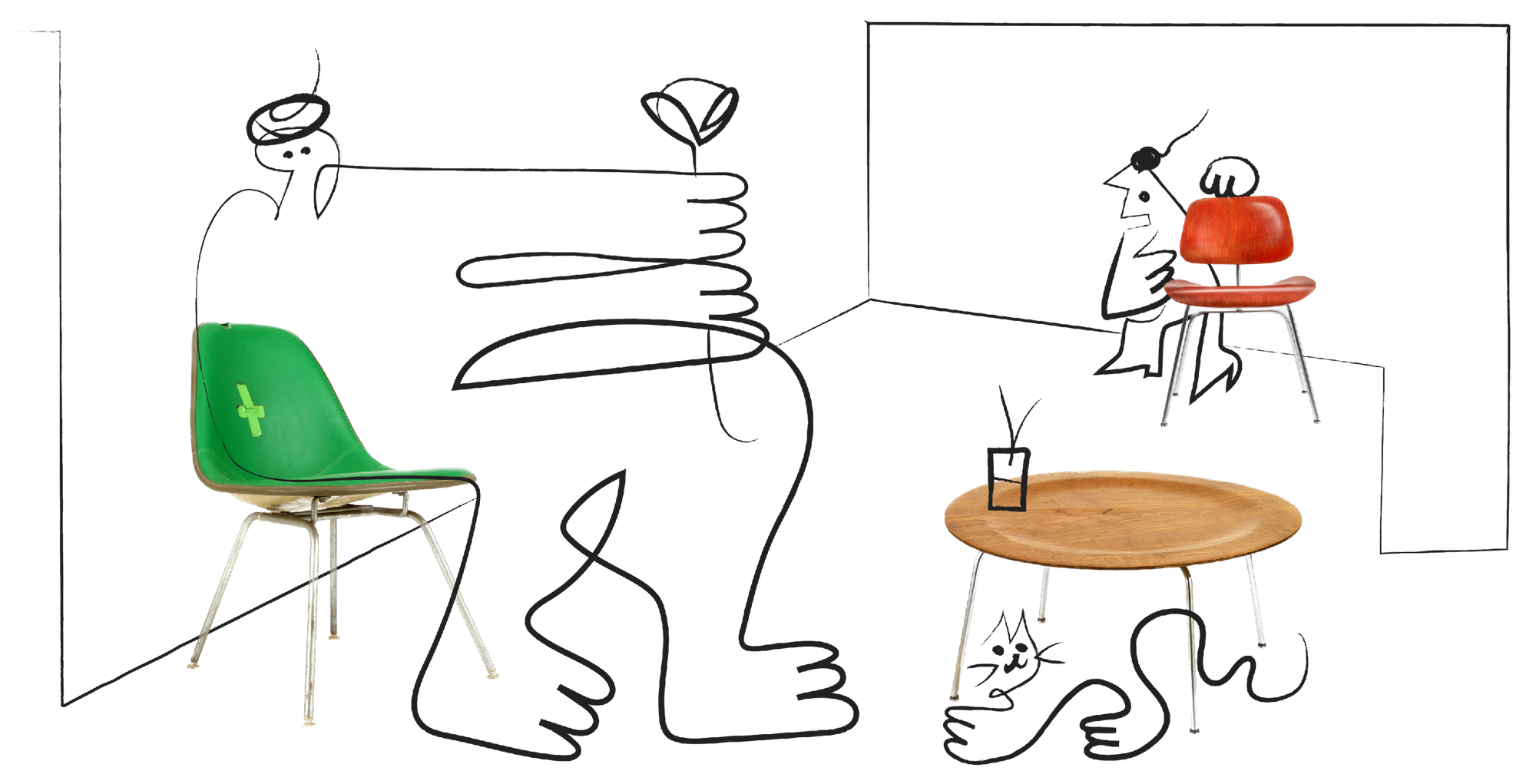

“In the same way that we appreciate the layers of paint that cover an old wooden barn, we can also prize examples of Eames chairs that the original owner repaired to extend its life or to make it more functional for their own specific needs. There’s an aesthetic to repaired goods, and it’s an extension of what Ray and Charles were thinking about. In the Eames Institute collection, we have this fabulous Eames fiberglass chair with green Naugahyde upholstery. A hole developed in the original Naugahyde covering and someone at the Eames Office, maybe Ray or Charles, took two pieces of light green plastic tape and put an X over the hole. It’s one of my all-time favorite chairs. Taking that as inspiration, if you have a chair with purple Naugahyde that has a gash in it, cover the gash with some purple tape so it won’t get worse, and you’ll have a perfectly serviceable chair.”

Earlier isn’t necessarily better

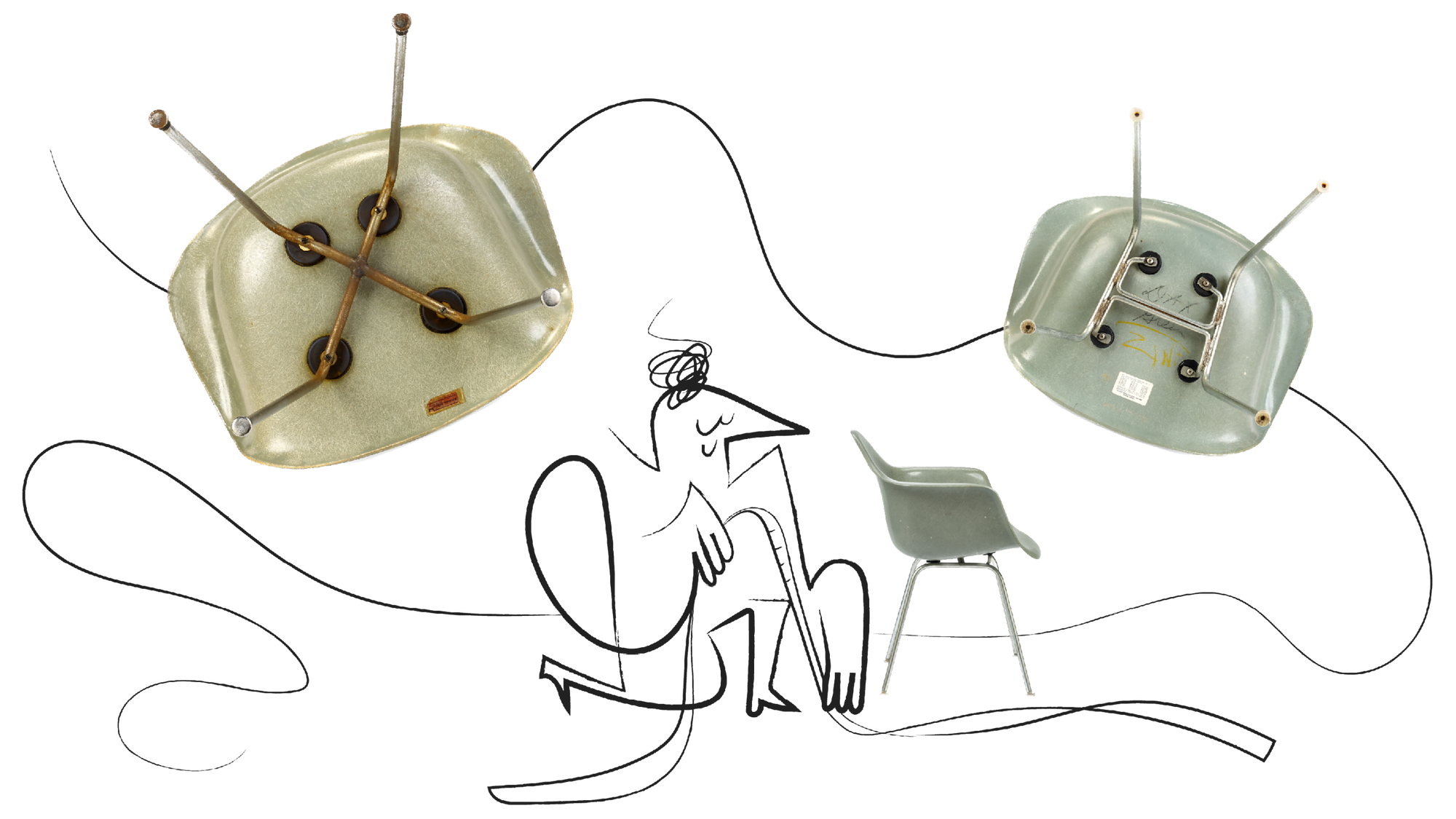

Ostroff: “There is a tendency in the Eames world now to focus exclusively on early examples of the Eameses’ furniture. But because Ray and Charles were always improving their designs, those early versions might not always be the better designs. For example, after four or five years of making a four-legged fiberglass chair base with one point of connection in the middle, forming what looks like an X, Charles and Ray modified that, and made a base that looks like an H. They did that because the X base, with only that one point of connection, had a tendency for the legs to splay. If people are looking for the earlier examples, they want the X-based chairs—but the H-base is technically a better design. I advise people to consider the context and to consider the designer’s process. There are wonderful opportunities in collecting vintage Eames from every decade.”

Beware of FrankenEames

Ostroff: “As a collector, you want to find pieces that have their original bases, and there are some small details that can help you verify this, like the condition of the screws in the base. A shiny screw is suspicious. Invest in a small flashlight-size UV light. You can shine it on an antique, which should have a consistent glow to it. If, in UV light, one part or another glows brightly in contrast to the rest of the design, that bright glow is probably an indication of a repair or replacement part. Other details are helpful in confirming authenticity: collectors have learned which chair leg glides are consistent with which era of chair manufacturing, for instance. With fiberglass chairs or molded plywood chairs, collectors will look closely at the shock mounts on the underside, because you can tell if the mounts are original and which base was originally married to that chair. If the shock mounts are dented in such a way that indicates it was once a stacking chair, and someone has put it on a rocking base, I would call that a Frankenstein chair, and I’d stay away from it.

“There’s this terrible thing that has gone on for more than 20 years in Europe, where non-serious dealers buy Eames shells in the US, throw away the bases, and then have the shells shipped to Europe. They marry real shells to bases that are imitations and then they try to persuade people that it’s an authentic 1970 chair. This is ironic, because you can more easily date a chair by its original base, than by the shell. Charles and Ray improved upon the bases several times, providing a bellwether of their age. So if you buy an Eames chair, have it shipped to you fully assembled. Once screws have been taken out, the chair’s authenticity may be hard to verify. And if a rocking chair base is removed, there’s a chance you won’t be able to get it back on.”

Become an Eames librarian

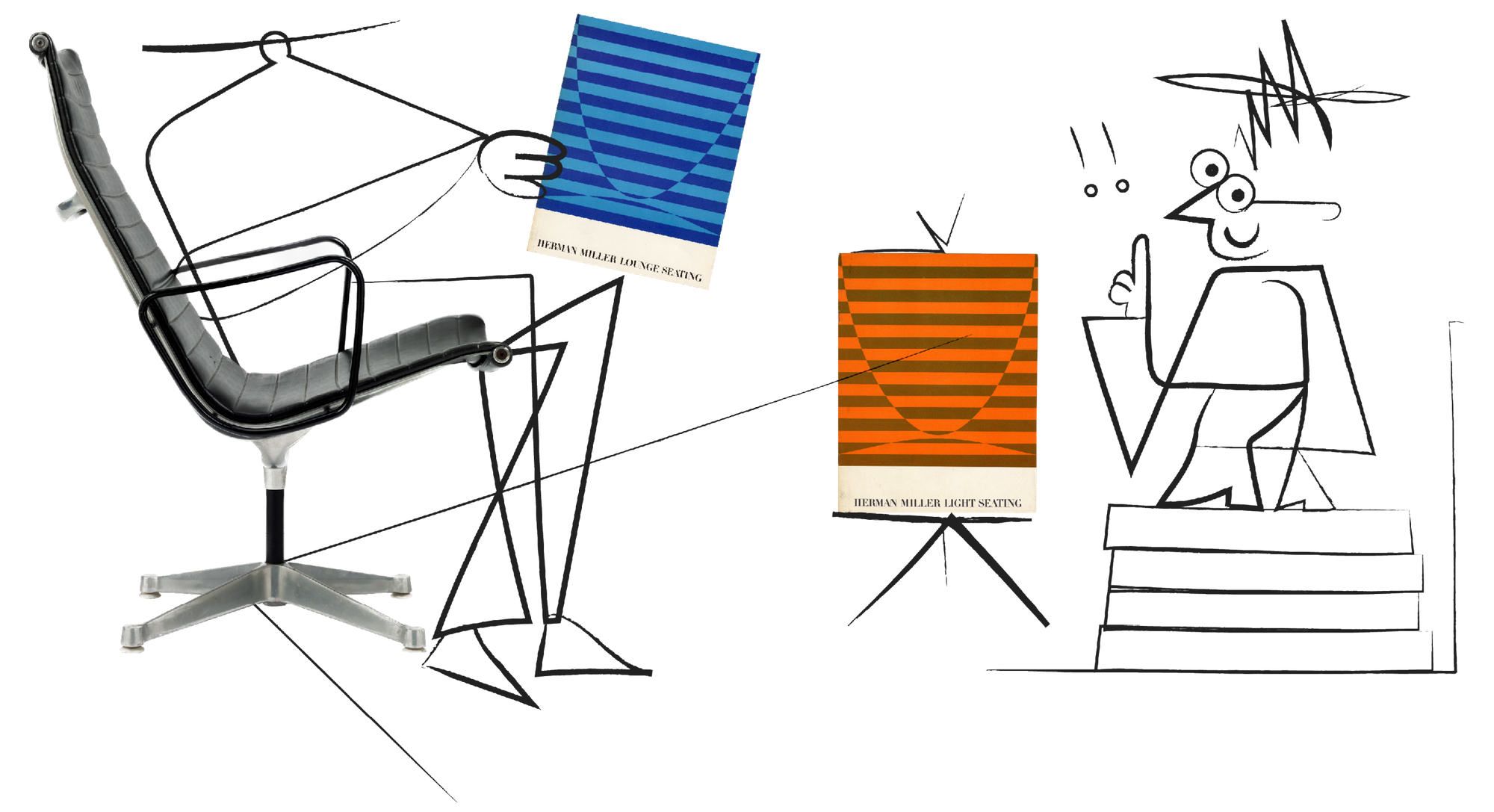

Ostroff: “I recommend that aspiring collectors read as much as they can to learn about the Eameses and their work. To start, collectors can find original and reproduction copies of vintage Herman Miller catalogs and ‘price books’ listing the Eames offerings that were being produced in any given year. What you can get from these are correct model names and dimensions. But what is missing from these resources is information about the original details that are useful in dating a chair.

“To learn about the Eameses’ design process, there’s a wealth of information in various books and publications. What ignited my interest in Ray and Charles’s design process was an exhibition catalog called Connections: The Work of Charles and Ray Eames, which accompanied the 1976 exhibition of the Eameses’ work at UCLA. There are fabulous pictures in there, and the essay was written by Ralph Caplan—someone who understood the Eameses deeply. I would follow that with Eames Design and An Eames Anthology.

“When I edited An Eames Anthology, I specifically included seven texts about furniture, in which you can read Charles’s explanations of the furniture concepts in his own words. Following that, there are two biographies, one by Pat Kirkham titled Charles and Ray Eames: Designers of the Twentieth Century, and one by Eames Demetrios, An Eames Primer. The latter book is unique in that it is the first biography written by someone with direct knowledge of Ray and Charles, who also had access to all of their personal archives. You can bookend these readings with catalogs that accompanied other major exhibitions, like the Library of Congress’s The Work of Charles and Ray Eames: A Legacy of Invention, and the 2015 Barbican exhibition, The World of Charles and Ray Eames. The Eames Furniture Sourcebook, published by the Vitra Design Museum, has invaluable information and history as well. For further investigations, you can explore The Design of Herman Miller, by Ralph Caplan, and Herman Miller: A Way of Living.” ❤

A film producer and an Eames expert, Daniel Ostroff has worked with the Eames Office since 2006, and with the Eames Institute since 2019.

Catherine Potvin is a visual artist based in Montréal, Canada. The spirit of her work is both playful and grunge; the finesse of her simple lines mixed with complex irregularities support her constant quest for the perfect imperfection.

At Kazam! Magazine we believe design has the power to change the world. Our stories feature people, projects, and ideas that are shaping a better tomorrow.