Design Q&A: Emily Pilloton-Lam

At Girls Garage, Emily Pilloton-Lam guides girls and gender-expansive youth to design interventions for social and personal good.

Emily Pilloton-Lam in the workshop-classroom of Berkeley, California–based Girls Garage.

“Design does not exist without the fundamental belief that we can always do better, be better, make better,” says Emily Pilloton-Lam. This optimistic worldview is deeply engrained in the work of the designer and educator, who has consistently channeled design as a force for positive change at the individual, community, and global levels.

In 2008, Pilloton-Lam founded Project H Design, a nonprofit focused on catalyzing and delivering humanitarian products that improve quality of life. The initiative’s first project was to redesign the Hippo Roller, an innovative device that allows users to easily transport up to 22 gallons of water—thus reducing burdens on residents living in areas with limited access to water. In addition to improving the design, Project H raised enough funds to deliver 75 rollers to Kgautswane, a rural community in northeastern South Africa.

Tiny homes designed by Studio H high school students for a residential center for unhoused citizens. Photograph: Emily Pilloton-Lam

The Windsor Farmers Market pavilion was designed and built by Studio H students in Bertie County, NC. Photograph: Brad Feinknopf Photography

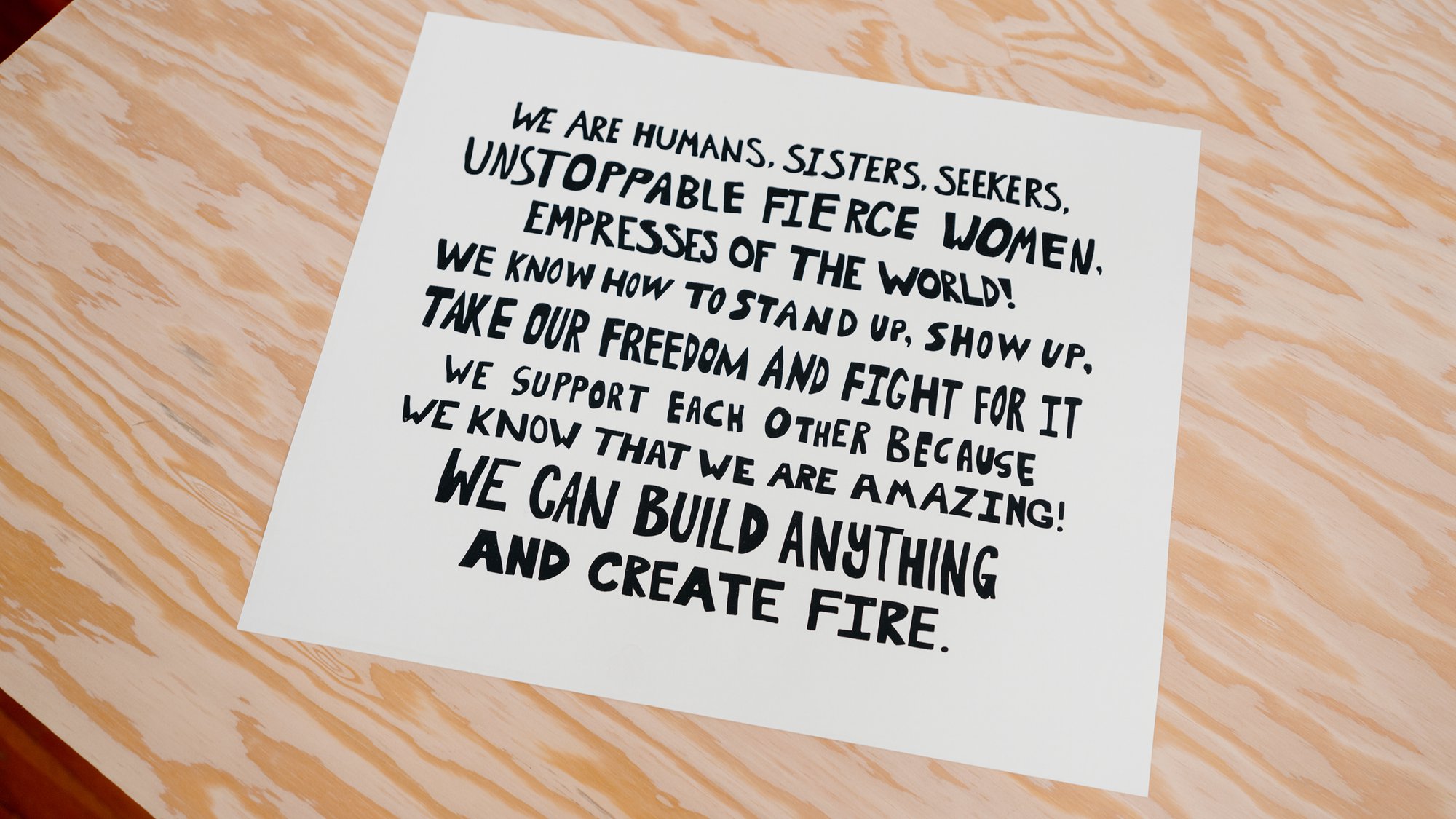

Pilloton-Lam went on to cofound Studio H, an educational program where high school students learned to design and build socially transformative projects ranging from a 2,000-square-foot farmers’ market pavilion to a pair of tiny homes for unhoused individuals. Pilloton-Lam noticed that in planning and crafting these ventures, her female students often allowed boys to take the initiative. So she launched Girls Garage, a workshop and design/build program that empowers girls and gender-expansive youth to “build the world they want to see.”

Based in Berkeley, California, Girls Garage offers after-school and summer courses ranging from carpentry and welding to activist art, with a focus on community leadership and learning by doing. “The projects we build exist in the world as expressions of our hope,” Pilloton-Lam says. “I am only interested in using design as a source of power and voice that makes physical the hopes and dreams of the next generation.”

In the 1972 film Design Q&A, French curator Madame Amic presents Charles Eames with a series of archetypal questions about design’s meaning and purpose. As part of an ongoing feature in Kazam! Magazine, we posed those questions to Emily Pilloton-Lam.

Q: What is your definition of design?

A: For me, design is optimism in practice. It is the instinct to build and make, coupled with a mindset that centers on love and hope.

Q: Is design an expression of art?

A: One thousand percent yes. It took me two years of art school to realize that design can and should start within ourselves. Design usually begins with the client’s needs, and while those are important, it’s also important to tap into who you are, and how the challenging aspects of your identity are expressed through design. In this way, art, which is so much about self-expression, has a lot to teach design.

Q: Is design a craft for industrial purposes?

A: I’m sure it is, and has been, but this has never been my interest. So much of design gets lost when we’re only thinking about the scale of production.

Q: What are the boundaries of design?

A: I am often asked by my high school students who are interested in studying engineering, or architecture, or design, “What’s the difference between engineering and design?” When I think about the “boundaries” of design, I’d like to think they are boundless—but I can definitely tell when something has not been designed. So perhaps the boundary between design and engineering (or anything else) is that design has that little something extra that delights, or surprises, or challenges. It is meant to elicit an emotional connection, not just a functional gratitude.

Q: Is design a discipline that concerns itself with only one part of the environment?

A: Never. Design’s very nature exists at the intersection of multiple challenges. When I’m building with my students, they are often surprised and excited to learn that a seemingly simple project, like a greenhouse, is about so much more than the structure— it’s also about ecology, light, community, and growth.

Q: Is it a method of general expression?

A: Design is a method of expression and a way of thinking—of navigating the world. I believe that to identify as a designer is to say out loud that I am a builder, a maker, a critical thinker, and a lifelong learner.

Q: Is design a creation of an individual?

A: Yes, but I often find individualistic design to be obnoxious and disconnected. Plus, it’s just not as fun to design something alone!

Q: Is design a creation of a group?

A: I believe it should be. This doesn’t mean it must be “design by committee,” but engaging in design with a group is like a form of activism: It calls us to ask what’s important to us as communities, and to manifest our response in physical form.

Q: Is there a design ethic?

A: I’d like to think designers share their own Hippocratic oath to “do no harm.” I remember reading an article about 15 years ago that made a devil’s advocate argument that the AK-47 was the best product design of the last century. While I can objectively understand the (brutal and unnecessary) function of that object, you will never convince me that it’s good design. I can’t speak for the entire community of designers, but for me, the ethic of design is built on a belief in people, the planet, and that we always have the power to design a better version of the world.

Q: Does design imply the idea of objects that are necessarily useful?

A: Some of my favorite objects are not all that useful for practical matters in the way that a kitchen utensil or commonplace tool is—but aren’t delight and joy useful as well? I have so many objects that were at one point designed, and that I have carried throughout my life. They bring me happiness, a sense of connection to my ancestors, and comfort. So yes, design implies usefulness, but usefulness can mean so many things.

Q: Is it able to cooperate in the creation of works reserved solely for pleasure?

A: Absolutely. See above.

For me, the ethic of design is built on a belief in people, the planet, and that we always have the power to design a better version of the world

Emily Pilloton-Lam

Founder and executive director

Girls Garage

Q: Ought form to derive from the analysis of function?

A: Thinking about design as a “first this, then that” formula has never really worked for me. I design and build so many things with young people, and they have helped me rethink the “order of operations” of design. For example, one of my students once said, “I want to build a table that looks like a cat.” She didn’t care so much that the table was structurally brilliant, but she definitely cared that it was an homage to her furry friend. We worked on the function to reflect the feline form, and it was a design that she was deeply proud of, and that will mean something to her for years. So, whether we begin with form or function feels like the wrong question to me—rather, we should start by investigating, what’s the purpose and meaning?

Q: Can the computer substitute for the designer?

A: Never. Sorry, binary code! This may be an unpopular opinion, but while I believe problem-solving can be mechanized and coded, what makes design design is the human subjectivity, opinions, feelings, and idiosyncrasies that we all embody. There is also an element of service between humans that design fulfills, which computers cannot grasp. But I’m old school.

Q: Does design imply industrial manufacture?

A: In some cases, I believe that industrial manufacture actually runs counter to design. Of course, objects are often designed for mass production, but that is more about the artifact than the process. Design is scaleless as a process and makes no demands on making one, or one million, of a thing. Some of my favorite design projects are one-off architectural structures that were crafted bit by bit, not manufactured, such as the rammed earth structures by Design Build Bluff.

Q: Is design used to modify an old object through new techniques?

A: I love fixing things—repairing and renovating. I absolutely think these processes require a design mindset, and that they’re rooted in the same idea: “I can always build a better version.”

Q: Is design used to fix up an existing model so that it is more attractive?

A: I’m not really one for “makeovers” for aesthetic purposes only. That said, one can of paint can change an entire space’s dynamic and make people feel welcome, happy, and calm. In this sense, I’m in favor of the editing of space and objects, because it keeps us mindful of, and thinking about, how our physical world works for us.

Q: Is design an element of industrial policy?

A: Not nearly enough. I often look at policy and policy makers and think, “There isn’t a creative person in that whole bunch.” Imagine if policy makers were wildly creative thinkers and were willing to eschew the precedents they knew to be foundationally flawed. Creativity takes bravery and a deep sense of hope, and I think that’s a trait we all wish our policy makers would put into practice in more tangible ways.

Q: Does the creation of design admit constraint?

A: Some of the most brilliant designs make you forget there were constraints in the first place! I love hearing the backstories of some of the designs I love, and understanding the challenges the designer was wrangling with, only to realize that the final product is such a graceful and smart resolution of those challenges.

Q: What constraints?

A: Constraints can come from so many angles: the physical limitations of an architectural site; the climate or environment; the limits of a material’s properties, cost, values and ethics; and time. I personally love working under multiple pressures, and I love presenting constraints to my students as mountains to climb. Constraints make design goal oriented while also shaping decisions along the way.

Q: Does design obey laws?

A: I do wish design had a public commitment to “do no harm,” like the medical profession or other professional communities. Apart from that, there is a lawlessness to design that is exciting to me: there are constraints, of course, but what you do within them can be pushed against, fought for, and broken through. I love the idea of using design as a tool to break rules—both within the design itself, and in our own minds and systems.

Q: Are there tendencies and schools in design?

A: Absolutely. So much of design education feels connected to the people teaching it, who bring their oral tradition, how they were taught, and their own identities into their interactions with students. I know this is true for me: when I’m teaching a class of young women, we’ll often begin by talking about a design project and end up discussing racial identity, or interpersonal challenges. It’s important to me that the teaching of design makes space for who students are, and how they show up every day. My own “school of design” is deeply connected to my identity, and I want to give my students permission to express all of who they are: They don’t have to check anything at the door. It makes our creative work better, and our design community stronger.

Q: Is design ephemeral?

A: I sincerely hope not. Because I work in wood, metal, and physical space, ephemeral is something of a bad word. I want to think about, and build things, that last in the physical world and in people’s emotional memory.

Q: Ought design tend toward the ephemeral or toward permanence?

A: I think every designer must consider where their work falls on this scale—both for the user and for the planet. For example, a plastic straw that is used for five minutes is ephemeral to humans, but it’s closer to permanent waste for the planet. This is horrible design. Design can be momentarily useful or last forever, but in either case, its intent should match its actual impact. Personally, I am more drawn to design and objects that stay in my use for a long, long time. These are the objects of meaning, the heirlooms, that I love.

Q: How would you define yourself in respect to a decorator? An interior architect? A stylist?

A: Designers wear many hats, so I have definitely played all these roles. Most great designers are defined by their ability to code-switch between these jobs gracefully, and at a moment’s notice. Because I am also an educator of young people, I often serve as a carpenter one minute, a decorator or painter the next, and then a nurse, big sister, and caretaker. Playing these multiple roles is a way of practicing responsiveness and empathy.

Q: To whom does design address itself: To the greatest number? To the specialists or the enlightened amateur? To a privileged social class?

A: I answer to myself, to my students, and to my community, in that order. I must show up as a creative leader grounded in who I am, what I am willing to do and not do, what I love, and who I serve. I serve my students first—the young people who are excited to design and build a world they want to live in—and I think of design with my students as a tangible tool to impact our community. The projects we build exist in the world as expressions of our hope. I am only interested in using design as a source of power and voice that makes physical the hopes and dreams of the next generation.

Q: After having answered all these questions, do you feel you have been able to practice the profession of “design” under satisfactory conditions, or even optimum conditions?

A: I feel I have been able to create my own conditions in which to practice design, and introduce different conditions for the next generations to think about design, which feels gratifying and exciting.

Q: Have you been forced to accept compromises?

A: Surprisingly, no. I may have to alter the details of a project, but with my students I try to maintain a practice of knowing our core beliefs and values, and not compromising on those.

Q: What do you feel is the primary condition for the practice of design and for its propagation?

A: Hope and love. You cannot be a designer without a deeply rooted belief in the future, and a love for people and planet. I wake up every morning excited and grateful to be alive and to get to make incremental change in the world. To do this with young people means being surrounded by a community of learners and makers who embody hope every day. Design does not exist without the fundamental belief that we can always do better, be better, make better.

Q: What is the future of design?

A: The future of design—and the future of everything—resides with the next generation of creative young people. It’s exciting to me to think about passing the torch to the young people I have the privilege of teaching. They are far bolder, more concerned with equity and activism, fiercer and more equipped for what is to come. I don’t know what their designs will look like, but I’m thrilled that the future will be in their hands. ❤

At Kazam! Magazine we believe design has the power to change the world. Our stories feature people, projects, and ideas that are shaping a better tomorrow.