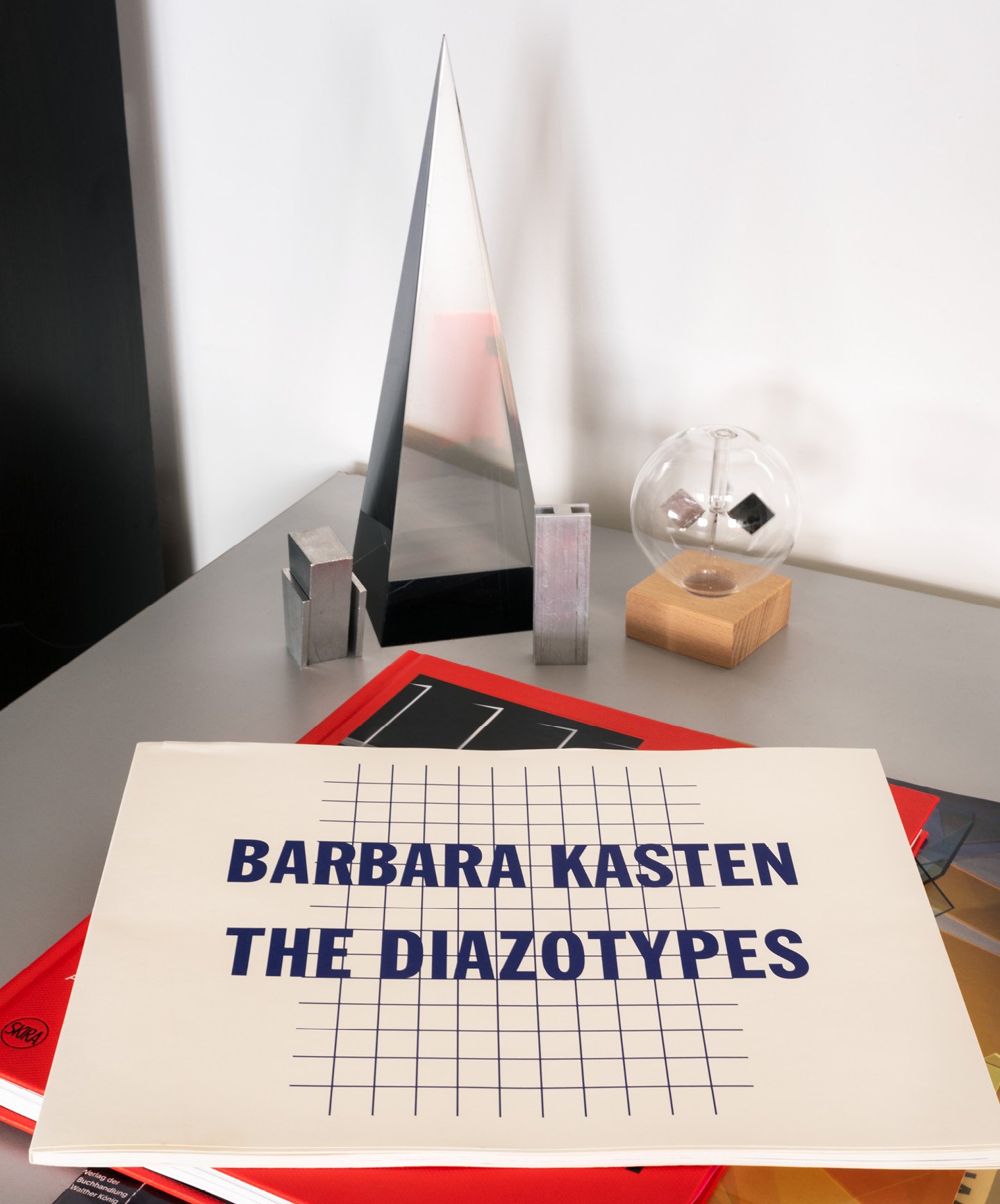

Design Q&A: Barbara Kasten

Working with a lyrical palette of light, form, space, and time, Barbara Kasten investigates abstraction, ephemerality, and the notion of artwork itself.

Artist Barbara Kasten photographed in her Chicago studio with SHIELD XXIII (2022), left, and acrylic prototypes for Parallels (2018), right.

It would be convenient to say that Barbara Kasten works in photography or sculpture. The output of this Chicago-based artist certainly fits within these traditional categories. Over the course of her decades-long career—from her 1970s experiments in abstraction using cyanotype photograms to recent ballroom-scaled commissions—she’s skirted categorization, producing images and installations that capture, sometimes fleetingly, that which is ineffable. Which is to say, her true mediums are neither film nor stone, but rather light, space, and time.

At 88, she’s in the midst of a late-career renaissance fueled by the 2015 retrospective Barbara Kasten: Stages. The exhibition highlighted her multidisciplinary approach. It opened at the Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania and traveled across the country. The accompanying catalog carefully tracked Kasten’s peripatetic biography: BFA in painting at University of Arizona, time spent in Germany, her discovery of Bauhaus weaving that led her to a fiber arts graduate program in Oakland, California, an immersion in the Light and Space movement and conceptual photography.

While a retrospective often marks the late period of an artist’s practice, Stages introduced her art to a new generation. Fresh audiences fell under the spell of her Constructs series—the geometric still-lifes that use artificial light, gels, and sometimes mirrors to conjure an illusionary image. Last year she released Barbara Kasten: Architecture & Film (2015–2020); reflecting on her most contemporary work, the monograph places Kasten squarely in the present.

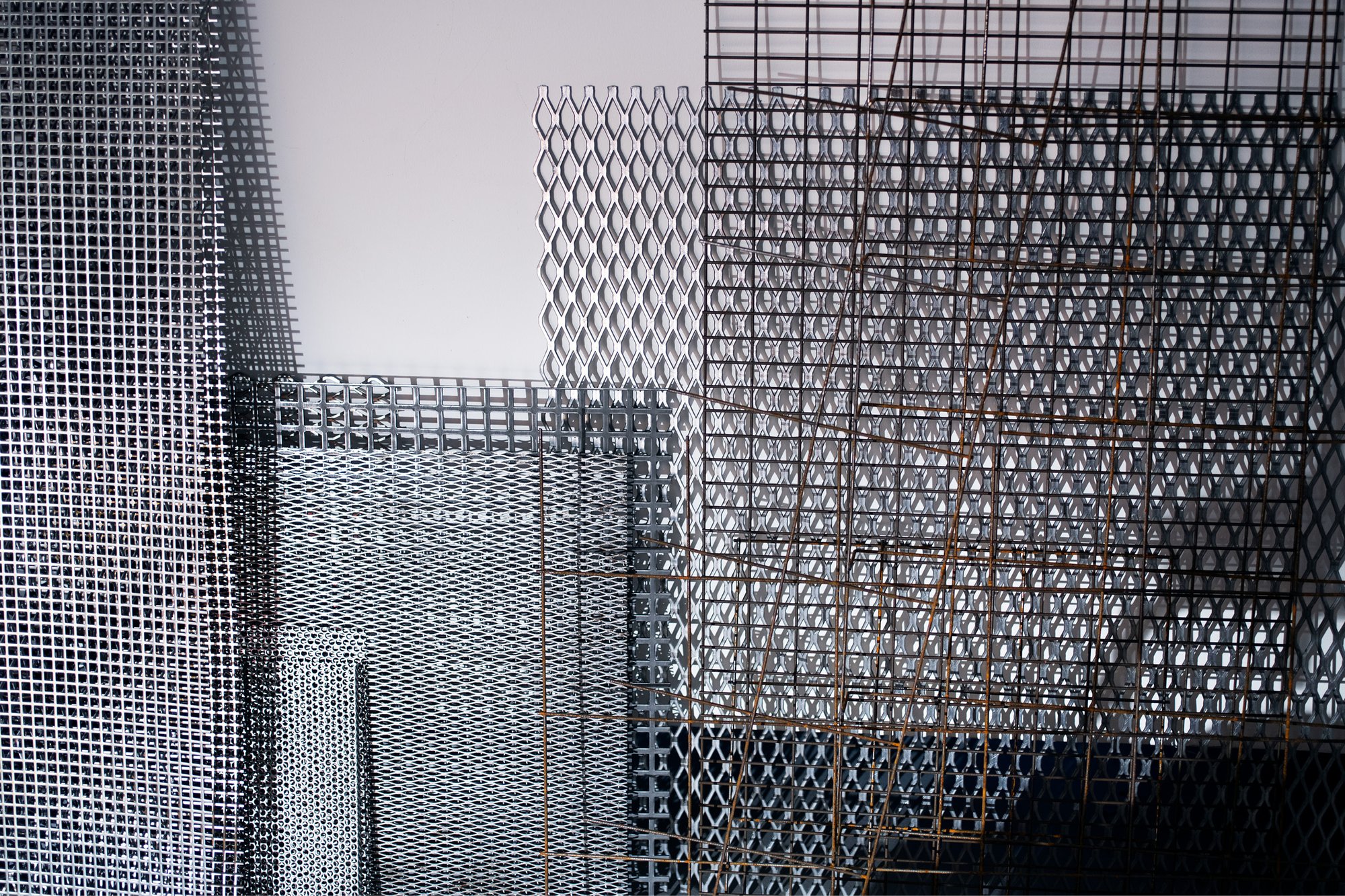

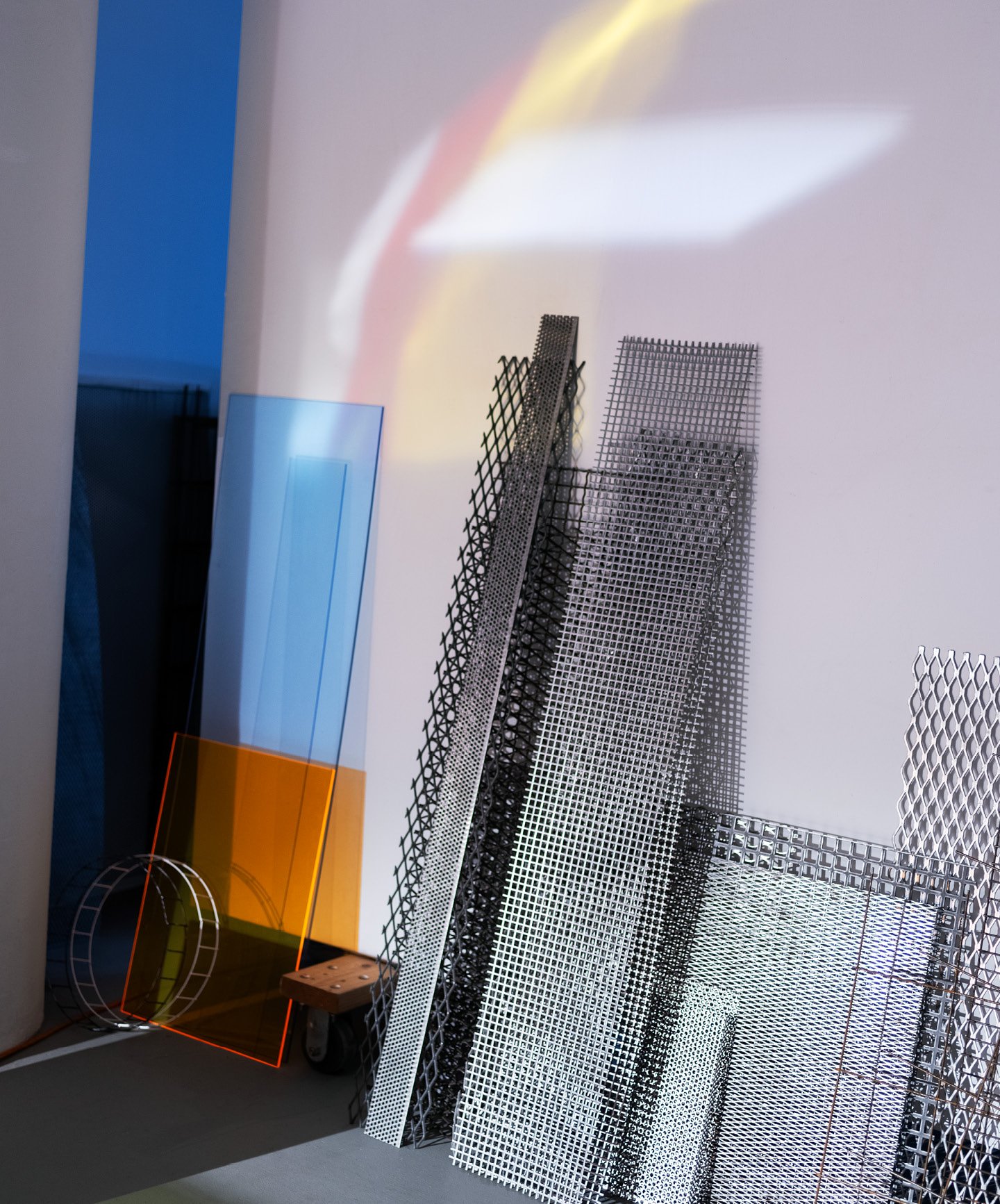

In the summer of 2024, Kasten completed an ambitious site-specific installation at the De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill on the southern English coast. A modernist folly built in 1935 by architects Erich Mendelsohn and Serge Chermayeff, the pavilion’s main gallery has huge picture windows that gaze out onto the boardwalk and the sea beyond. It’s a tranquil setting enlivened by Kasten’s construction, Site Lines. She filled the hall with slabs of colored plexiglass that lean precariously against the glazed façade, then arranged a chorus of stage flats hung with undulating mirrors. The result is a funhouse of color and reflection that changes as sunlight illuminates the space. There is never one single “decisive moment” frozen on film, to coin a photographic phrase. Compositions continually combine, fragment, and realign as visitors weave through the exhibition.

“A lot of my practice is shifting to interactions with natural light, rather than the controlled studio lighting I’ve always worked with,” says Kasten, recalling the kaleidoscope-like interior of Le Corbusier’s Ronchamp chapel. “Things happen with materials that only occur with light—that mysterious effervescence of the light reacting with the material.”

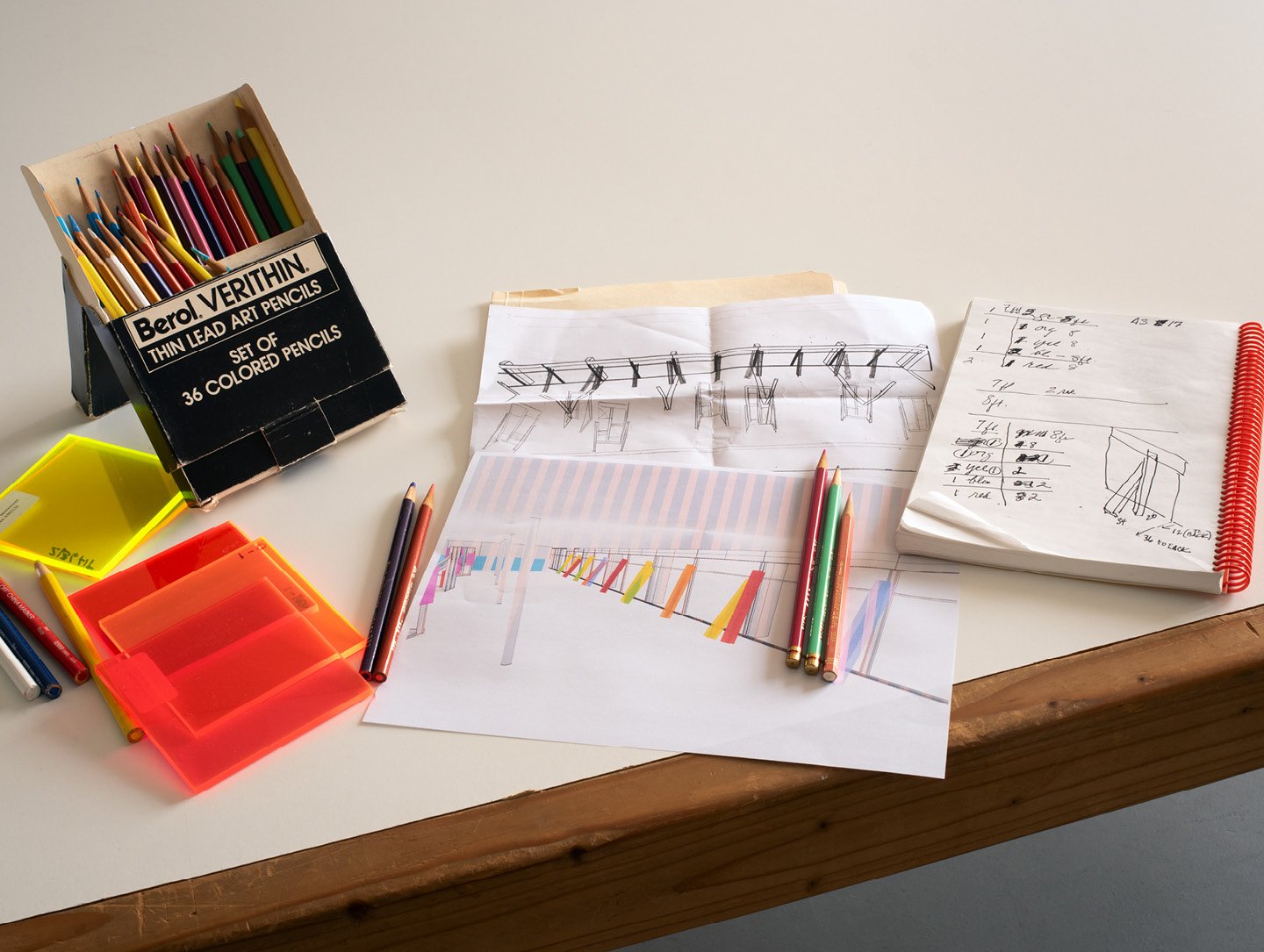

Site Lines is the latest in a series of artworks that destabilize and reimagine architecture. As part of a 2018 residency at S. R. Crown Hall on the Illinois Institute of Technology campus—a place designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and not far from the Chicago neighborhood where she lived as a child—she upended the metal drafting desks used by architecture students. With the addition of candy-colored plexiglass, she remade the interior of the modernist jewel box into an abstracted collage of line, shape, and hue.

Kasten cites Bauhaus influences, especially the work of László Moholy-Nagy, as essential reference points underpinning her spatial alchemy. Her work, however, has evolved over the years from carefully collapsing architectural space within a frame of the lens, as she did in her Architectural Sites series from the 1980s, to using the perceptual properties aligned with photography—light, shadow, pattern—for sculptural effect.

Another modernist building is on her horizon: Philip Johnson’s Brick House. Kasten returned to cyanotype photograms to develop a series for the recently restored structure (and dark twin of the Glass House) on the architect’s property in New Canaan, Connecticut. The camera-less technique of exposing emulsion to daylight is one of the oldest photographic methods and a favorite of Moholy-Nagy.

Like her predecessor, Kasten experiments with the medium, pushing it toward abstraction. She builds up an indigo and white image by layering objects and their shadows. But it begins with a painterly gesture, which brings a depth to her explorations while recalling her earliest art practice. “With something so simple, you would think that there’s no way to make it different, but there is,” says Kasten. “There’s always a way to make it your own.” The same could be said of her creative practice. With each chapter, with each experimentation, she’s made it her own.

In the 1972 film Design Q&A, French curator Madame Amic presents Charles Eames with a series of archetypal questions about design’s meaning and purpose. As part of an ongoing feature in Kazam! Magazine, we posed those questions to Barbara Kasten, altering them slightly to focus on her practice of art.

Q: What is your definition of art?

A: Art is one of the most important experiences of human existence. It encompasses so many different aspects of life, cultures, and creative processes that it is almost undefinable.

Q: Is design an expression of art?

A: Design is an expression of oneself. I live with objects that are beautiful, function well, and mix them with other objects that remind me of different times in my life. I arrange things in my personal environment with the same kind of sensitivity I have when building a set for a photograph.

Q: What are the boundaries of your practice?

A: Boundaries are essential to my art practice. They guide me and keep me focused on the problem I’m working on. The art, however, has no boundaries. It’s the experimentation, the discoveries, and the process that interest me and guide me toward the completion of an artwork.

Q: What are the ways your work engages with the built and natural environment?

A: I look at architecture as a sculptural construction in space. The shadows created by changing light add depth and form. When arranging the elements of an installation for either the camera or to be experienced in real space, the negative space is as important to me as the physical materiality. If the artwork engages with a specific architectural site, the environment is not only a location but can also reveal character, history, or purpose.

Q: Is art or design a creation of an individual or a group?

A: Art and/or design can be created by an individual, it can be a group effort, it can be a collaboration by two or more, it can be directed by one and performed by many. It can be any combination that works.

Q: Are you driven by an ethic, and if so, what is it?

A: My ethic is to be true to myself.

Q: In what ways do you see art as useful?

A: My work has been inspired by the practitioners of the Bauhaus, a group who used art and design to implement societal change. The artists were teachers who mixed media and disciplines to create new forms of expression. Photography was a new popular tool at the time that had uses for a variety of purposes. My first photographic work was a photogram inspired by what Moholy-Nagy described as a direct connection to abstraction. I am convinced that abstraction can encourage independent thought, and I believe that art is useful to promote a positive way of life.

Q: Is art able to cooperate in the creation of works reserved solely for pleasure?

A: Pleasure in work that provides us with joy and happiness encourages us to believe in ourselves. It is rewarding in itself!

Boundaries are essential to my art practice. They guide me and keep me focused on the problem I’m working on. The art, however, has no boundaries.

Barbara Kasten

Artist

Q: Ought form to derive from the analysis of function?

A: I allow materials to create their own self-sustaining sculptural form. The inherent quality of a material manifests itself in unique and unexpected ways as it reaches a reliance on balance, shape, and weight to find harmony and stability with other diverse materials. In my constructions, light is the evanescent component that I introduce to the form to instill a mysterious coalition.

Q: Can the computer substitute for the artist?

A: The computer isn’t a substitute for my thoughts and ideas. Techniques that it provides are powerful tools with a new language for many people. I believe that the artist shares inner curiosities and thoughts that need techniques to express themselves, but it doesn’t happen the other way around.

Q: What is your approach to fabrication?

A: I hire someone with the necessary expertise to assist me. It is not efficient for me to learn all the techniques that can facilitate my concept. I work closely with a technician to understand and supervise the activity. The production may involve several disciplines but ultimately the decisions in each process are mine.

Q: Are you exploring any new photographic techniques?

A: My multidisciplinary approach to art began early in my career. For the last 50 years, I have continued experiments that merge newly discovered materials with more familiar ones from my past. I am curious about how the properties of common industrial materials transform into uniquely different identities with the addition of light. Light is essential to all my work. Since 1974, I’ve worked consistently with a camera-less photographic technique, the cyanotype photogram. The application of the chemical mixture with a brush merged my love of painting with my introduction to photography. Since then, I have combined the basic properties of photography with painting, in constructions for photographs, as principles of sculpture, as subject in video, and in multimedia installations. My most recent work follows in the same experimental direction with a closer focus on site-specific architecture.

Q: Does your work tend toward the ephemeral or toward permanence?

A: When I made three-dimensional constructions in the studio as a subject for my 4x5 camera, I referred to them as “sets.” After the photograph, the set parts were saved to be reused again. Flexibility and mobility became permanent features in my ongoing practice. I have an inventory of industrial materials and geometric plaster forms made to capture color light projections that I’ve repeatedly used in a variety of projects. The possibilities are endless.

Q: To whom does art address itself: To the greatest number? To the specialists or the enlightened amateur? To a privileged social class?

A: Art does not have a universal appeal. Appreciation depends on the individual, their life experiences, beliefs, education, vulnerability, etc. The viewer selects the art that they connect with.

Q: Have you been forced to accept compromises while practicing?

A: I have not compromised the content of the artwork. If it is necessary to consider revisions, flexibility and challenge can lead to interesting solutions.

Q: What is the future of art?

A: Creativity exists in everyone. If we are free to access it and express ourselves, art will thrive in the future. ❤

Mimi Zeiger is a Los Angeles–based critic and curator.

Kelli Connell’s work investigates sexuality, gender, identity, and photographer / sitter relationships. Her work is in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the J. Paul Getty Museum.

At Kazam! Magazine we believe design has the power to change the world. Our stories feature people, projects, and ideas that are shaping a better tomorrow.