Conservation Conversation

The heirs of the Eameses and Achille Castiglioni discuss the nuances, delights, and challenges of discovering and sharing their respective legacies.

Giovanna Castiglioni discusses the design legacy of her father, Achille, and her efforts to share his story as inspiration for future generations.

When I was traveling in Italy in the 1980s, I discovered an object that was so brilliant I had to possess it immediately. The piece, a spoon designed with flattened edges that were ideal for scraping out the insides of a jar, seamlessly blended utility with charm.

Unbeknownst to me, this was the work of the designer Achille Castiglioni. At the time, I had heard of Castiglioni and the lamps he made, but didn’t know that he had designed such an everyday object. Like many people who have fallen in love with Eames furniture before they know who the Eameses are, I was responding to the sheer power of Castiglioni’s design.

Years after that initial encounter, I rediscovered Castiglioni’s designs when I worked as an archivist in the Mies van der Rohe Archive at MoMA. The spoon was just one of a host of other remarkable objects that Castiglioni had designed with his brother, Pier Giacomo, including the Arco floor lamp, Mezzadro stool, and the ubiquitous, utilitarian light switch they created in 1968 for the company VLM. The designs integrated humor and whimsy and were always thoughtfully practical and beautiful objects.

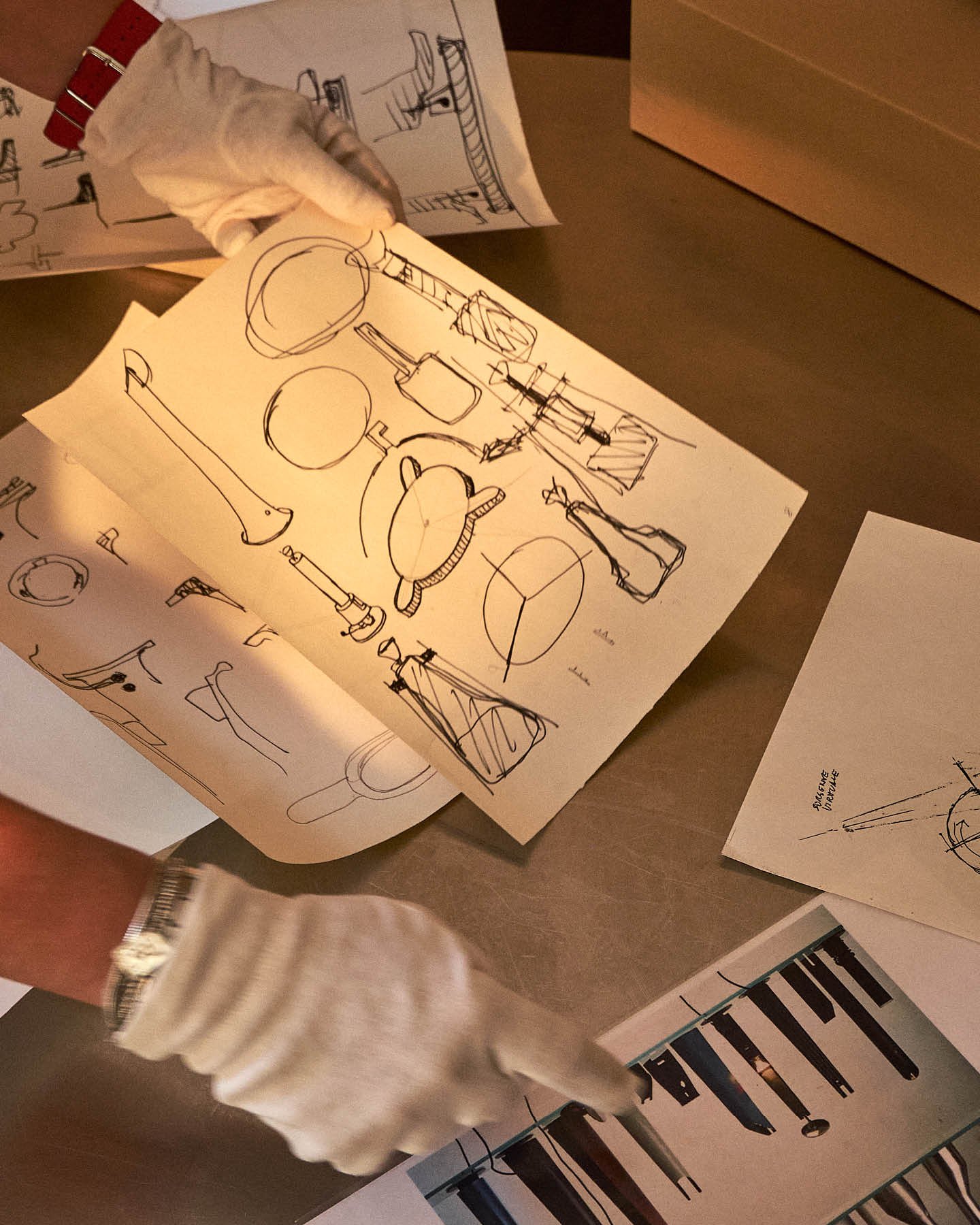

Castiglioni died in 2002, leaving behind an extensive legacy and studio full of drawings, prototypes, projects, and found objects. In the years following his death, Achille’s wife, Irma, transformed his studio into a museum, and in 2011, their children Giovanna and Carlo formed the Achille Castiglioni Foundation (Fondazione Achille Castiglioni en Italiano) working with former assistant Antonella Gornati to help maintain the space where he worked, read, dreamed, and designed. Giovanna began to give tours while the group, now assisted by digital archivist Noemi Ceriani, set about preserving and archiving the vast repository of work.

I visited the Foundation last April during Milan Design Week and joined Giovanna while she led a tour of the studio. I listened in as she talked about her father’s history and philosophy, showcased his designs, and explored the various ephemera he collected. As we wandered through the studio, I kept thinking again and again how we were seeing the same views that Achille saw. Our eyes scanned the same books that Achille read and contemplated. There was something in this space that informs the lasting power of his designs.

At the Eames Institute, we are grappling with a series of central questions: How do we best preserve and share the legacy of Ray and Charles Eames? How do we stay true to the history of these influential designers while inviting in new audiences? How do we reveal the creative process in a way that will offer inspiration for problem-solving the quandaries of today? These questions similarly animate the work of Giovanna Castiglioni, who strives to guide visitors–designers and the general public alike–through her father’s work so they will understand his process and his vision and their relevance to today.

Achille Castiglioni’s Milan studio, where he worked since 1962, became a foundation that has hosted tours since 2002. It is at risk of eviction in January 2024.

In Giovanna’s work, I found parallels to my own. Giovanna and I witnessed these iconic designers in the contexts of work and home, and we knew them both as our loved ones and as celebrated figures of design. We both seek to uncover and examine these layers as we explore the legacies we are sharing through our respective organizations.

This year the Foundation has reached a crossroads. The organization’s landlord has been attempting to evict it, creating the possibility that, as of January 2024, the Foundation may no longer be able to stay in the location where Achille worked. The potential departure threatens the tangible histories captured in the studio where Achille created so many of his important works. These nuances could never be transferred to another location. Aware of the fragility of connections between place and history, I felt an imperative to talk with Giovanna, to highlight the work of the Foundation, and explore its parallels with our work at the Eames Institute.

Llisa Demetrios, Chief Curator, Eames Institute

Giovanna Castiglioni, Vice President, Achille Castiglioni Foundation

In this conversation, Giovanna and I discuss the insights we gained from Achille, Ray, and Charles, and our roles as curators, family members, and lovers of great design.

Llisa Demetrios: There is something so special about being able to share your father’s legacy in the very space that he made the objects he designed. What do you feel is the importance of place as it relates to your father’s legacy?

Giovanna Castiglioni: The place is extremely important because it’s not only where Achille worked for many, many years, but it’s also the place in the center of Milan where there were other architects that stopped by the studio and were coming to visit Achille. They knew each other and spent a lot of time together—not only here in Achille’s studio, but also in other studios or close by in the Triennale or other museums. The studios of Marco Zanuso, the writer Umberto Eco, Franco Albini, and Vico Magistretti are very close to us. The place is so important for this generation of students and visitors, because even if the city and skyline are completely different nowadays, the core, the soul, is not only in this studio, but in other studios like the atelier that we have. This is why I want to save this studio right here—and not anywhere else. We say in Italian that the city of Milan is an amazing “museo diffuso”—in other words, like an expansive museum full of small cultural settings. In our “museum,” visitors can follow Castiglioni’s design process from the beginning to the end of the projects.

Llisa: When I was in the space, I was thinking of the decades that he was working, seeing the objects that your father surrounded himself with and worked on, seeing the view and imagining what he was looking at—all of that added a whole other layer to the archive and the work that you’re doing.

When Ray and Charles passed away, my mother focused on preserving their films and transferring them to digital formats. For you, what was the starting point of working in this archive and this amazing space that you’re preserving?

Giovanna: I originally trained as a geologist, so I began by studying the layers in our studio. My father passed away in 2002, and I’ve been in this studio since the beginning of this work. We understood from the start that you have to share stories, and at the same time you have to go deeply into the archive. So this is why we started both activities. Thanks to my colleagues Antonella Gornati and Noemi Ceriani, we are digitizing all the materials and trying to connect invoices, contracts, catalogs with photos, technical drawings and prototypes, and much more. Antonella is invaluable to this museum because she worked with Achille for more than 20 years. I continue to say that she is better than a computer or an Excel file.

To share stories and delve into the archive, I started to learn everything regarding Achille, and I started to do guided tours. But I had to learn everything. I didn’t know anything about Achille as a designer. As a father, of course, I knew him, but not as a designer.

Llisa: I completely understand that because I look at things as a granddaughter, and then I also look at things as a curator. As amazing as my grandparents were as designers, they were even more incredible as grandparents. I think your father would be in that category, too. Could you share about growing up with this, and how you navigate that juxtaposition of personal and professional after you opened the studio?

Giovanna: First of all, for me, Achille was just a father. It’s not important to me to say that Achille was famous. I don’t care—he was a normal man, a normal father, though he was not “normal” in a sense. He was absolutely fantastic, funny, and playful, with a wonderful sense of humor. He was also like a brother and sometimes a grandfather for me, because the age gap between us is quite big—I’m the youngest daughter in our family, and my brother is 20 years older than me. This gap was a good excuse for Achille to continue to play with me, and now I realize that it was a good excuse for him to continue to work. He used the relationship with his little daughter to continue to experience the freedom of play, and we enjoyed that together. And this is why I try to share this philosophy with visitors. If you love your work, you also love your life—and vice versa—so I think it’s so important to continually connect with that experience of enjoyment and play.

Llisa: Your father’s playful side makes me think about what Ray and Charles emphasized, which was, “Learning by doing.” After visiting with you, and thinking about the time with my grandparents, I think that phrase should be, “Learning by playing.”

Ray and Charles always said that they designed to address a need, and they considered design a method of action. The same could be said of Achille. Even something fun and whimsical, like a light switch—nothing was too small or too big for him to approach.

When I joined the tour of the studio, there were two school groups, and you could see them have this “Aha” moment of, “Wait—this work can be fun, too!” In that sense, design is a method of action that can bring joy. I think that’s an important message to convey, and you see it in Achille’s work.

My father said all the time, ‘If you are not curious, forget it.’ Curiosity is always around you, if you open your eyes to it. That curiosity shaped his designs.

Giovanna Castiglioni

Vice President

Achille Castiglioni Foundation

Giovanna: If you have an archive like this, you have to combine the spirit and the story. By sharing stories with humor, you’re helping others to learn by playing. If you are so serious, visitors start to get bored immediately. Personally, I love to engage visitors during my tours, lectures, or conferences with an interactive, immersive experience that is 360°.

When I was little and went to museums with my parents, it was absolutely frustrating—because everywhere they’ve written, “Don’t touch.” This was so strange for me. When we opened the studio, we said, “Okay, here you can touch everything.” These objects started with the industrial design field, which means mass production. So if you want to understand these objects, you have to touch them.

Llisa: And there’s something so tactile about the studio: You just want to touch everything. There’s a density of material and layers. Through that, you could start to see chain reactions involved in creativity: a book on a shelf, or the type on a cover, could relate to the chair in the room, and that then relates to a scale model. And that’s why I think it’s so important to observe those relationships physically, in the space, especially as we move into a more digital world. It’s illuminating for students today to see what your father saved, how he saved it, how he used it, where he used it—this reveals his process. You get that all right there inside the studio. And that’s why I want you to be able to save it and save it where it is. Trying to recreate that in another space would never be the same.

Giovanna: My father said all the time, “If you are not curious, forget it.” Curiosity is always around you, if you open your eyes to it. That curiosity shaped his designs. In every object designed by Achille, there is a reason [showing the Sleek spoon]. And if you have a reason, you win. You win because you solve the problem. Another example: Achille loved the Slinky toy and its spiral. Cini Boeri designed a sofa that had a similar form, and my father designed an ashtray with a similar coil. Why not? If you are a designer, you can translate objects into another form. The challenge is to translate objects into something completely different, if it’s possible. As we know from the Eames and Castiglioni method, the shape follows the function.

Llisa: Ray and Charles never wanted to make things once—they wanted to mass-produce things. They felt it could raise the bar of quality for everybody. Anything that they made, they called them gifts. And if you mass-produce something, you have more gifts to give. How did Achille feel about mass production?

Giovanna: His [VLM unipolar] light switch is the best example. This is mass production intended for everyone. My father never signed the contract, so just a few people know that the switch was designed by the Castiglioni brothers in 1968, but they didn’t want to receive the royalties from it. Achille just wanted to be sure it would go into houses and hardware stores, and that’s it. If you ask in a hardware store, who designed these? Electricians and people generally don’t know that it was designed by Achille. And this is the point. For Achille, it was absolutely important to arrive in every house, and sometimes he didn’t want to say, “This is my project.”

Llisa: The fact that he is in so many homes is clearly the reward.

Giovanna: Exactly. He was so happy to find his projects in a normal house, and when he found, for example, the switch close to the bedside table lamp in a hotel, Achille was so excited and happy. But he never said anything. He would be in a house where the people never knew that he designed something like that. This is completely different today. Because if you are a designer nowadays, you have to be a starchitect and count how many followers you have on Instagram. Achille was really humble, as Charles and Ray were.

Llisa: There are so many connections to Ray and Charles. They simply called themselves “tradesmen,” whose role is to solve problems.

I want to ask how you see the future of our archives. For me it’s that we can show how to solve problems related to the challenges that we face today. Ray and Charles’s way is not the only way, but it’s one way. What are you seeing for the future?

Giovanna: As you know, at this moment we received the eviction notice from the building owner, so we are working to preserve everything here. In theory, you can recreate the same museum in another place, but it’s not the same, because here you can still smell the cigarettes and the old books. You can see the same view that Achille saw, and you wouldn’t have that somewhere else.

We are working to preserve everything because we would like to connect the archive to the way it exists in this place. Or maybe we can bring this archive to another place in the future. All these archives, and not just ours, are in a fragile state. Not everyone is clear about what the future holds. Not everyone owns their own studio, which means they can be at the mercy of a commercial mindset that can easily close down spaces without thinking about what happened there. Milan, the design capital with a world of design that is slowly crumbling.

In your Eames heritage, you have granddaughters or grandsons taking care of the collection, and here you have the daughter and the son—and all of us want to save everything. But in other archives, sometimes the families are not able to spend money or put energy into huge archives like these. At the same time as we are struggling, our particular approach is to continue to share stories and to have a positive spirit.

Even if you put this archive into a venue like the Triennale Design Museum or the ADI Design Museum—assuming there’s enough space for it, which I don’t think there is—they can do two exhibitions in four or five years, but that’s not enough if we want to share the wisdom that is embodied in these collections. So if we want to remain in a place like that, we have to give younger generations the possibility to speak through the archive, not only about the archive. And our role is to be the soul of the archive. This is why we prefer to continue to share stories. We have to open the space to the public, and people have to feel that the spirit and the archive is alive.

Llisa: I agree. It’s only alive when it’s being played with—when people get to touch and look at the objects and be a part of it. For me, this is all about history and layers of time. My role here has been as a granddaughter and an archivist, but also as a historian. I love watching how the layers interlock, but also can peel back.

When my mom had to move Ray and Charles’s work due to a retrofit of their office in Los Angeles, she shifted the archive into her own space in Petaluma, where I live now, and she lived with the material, surrounded herself with her favorite objects, and experienced the “found learning” that you described. In that process, I think she realized that it can transition to somewhere else, like it can for you. Because the soul of your space is you, and the objects, and the work of your father.

For my mom, the transition became an exercise of discovering what were the most important qualities of Ray and Charles to share with the next generation, and that included the iterative process embodied in their prototypes: that you don’t just come up with one idea—you keep honing it and trying it out.

Giovanna: If I have to make this transition, and that’s the destiny of the archive, then I’m ready with a plan B. I’m like Mary Poppins—I bring Achille’s work with me in a suitcase and take lectures around the world. So I can do this work, maybe in another place. I also know that you and I are the soul of the space where we continue to share stories, but we are not eternal. We have to adapt our stories to a changing society—so who knows how our work might change?

Llisa: I love your spirit—you keep learning from the archive, just like I keep learning. I’ve been doing this for 25 years, and I’m still learning from my grandparents.

Giovanna: Yes, of course. And I’m learning from my father, still.

Llisa: My grandfather used to say, just because you know how a rainbow works doesn’t take away from the magic. I feel like you’re making discoveries, too, all the time. The reason I do this work is because I have found that looking at the past helps us inform and make better decisions for the future. And I feel that is very much what you do—this is not about you. This is about helping our next generation around the world.

Giovanna: Yes, this is the point. It’s important to give these languages to a future generation, so they can do the same in the future. I don’t want to be forever the daughter of, or the granddaughter of. It’s not about me or you. It’s about the design world. The design world has to be responsible for sharing this kind of approach that we see in these archives and the design work. Like a sponge, they have to absorb the information through us, and then they have to tell it to other people, and so on.

Llisa: You’ve allowed younger designers to intervene in the collection or to rearrange the collection. What have you learned from that process?

Giovanna: For temporary exhibitions, I’ve asked young designers to help me reorganize the studio. I prefer to ask a young designer, because for them, I know it’s a big responsibility, but at the same time, if we play together, work together, and go deeply into the archive together, we can experiment and use this studio like a case history. I work well with the designer Marco Marzini for temporary exhibitions, and he is so smart and perfect when he realizes an exhibition in our museum. He always manages to be effective: his exhibitions combine a sense of humor, overview of the project history, interaction with the public, and a very clear narrative of the design process.

Llisa: I’m very curious to see how designers today take these ideas and what they do with them. That’s when it comes alive for me. I love when someone comes back a few years later and says, “That story you told reminded me of this and led me to this.” I want everyone to have their own chain reactions. I want one thing to lead to another, and to another. I have no idea where it’s going to go, but I think it’s very exciting to be a part of this handing of the baton to the next generation.

Giovanna Castiglioni holds a splint given by Charles Eames to her father, Achille.

Giovanna: Yes, Llisa, you’re right. Marco’s work for us is continually creative and different from anything else that he designs. But you sparked another thought: During my guided tours or lectures, I love to ask someone, what is this [shows collapsible vegetable basket]? If they don’t know, whatever their answer is, I say, “That’s good.” There isn’t a “correct” answer. They are all valid. So if you say it’s a fruit or vegetable box, it’s good. If you say it’s a teapot, it’s good, if you say this is a crown, it’s good. I don’t want to say, “No, it’s wrong,” because by saying that, you frustrate people. You say that they are not able to learn. This is influenced by my father, who always said to me, “Try, try to do something. If you’re wrong, never mind.” This is why I like to give carte blanche to those who work with us. I like to live life as a continuous research endeavor, always maintaining curiosity towards the unknown. Then, if we make a mistake, we can start again from the beginning with humility and patience.

Llisa: I agree. Ray and Charles would always say, “The first way you try to solve the problem may not be the answer, but it will inform the next version that you do.” Your father and my grandparents made a series of choices—and we all have choices, and we are all working within constraints. I love the beauty of the choices that they made, and they never felt like they compromised. But they were always adding and imbuing and bringing such joy.

Giovanna: This is the soul of this point. It’s true. I agree with you and it’s an honor to talk to you and find so many points of connection between us. Thank you! ❤

Llisa Demetrios is chief curator of the Eames Institute of Infinite Curiosity and the youngest granddaughter of Ray and Charles Eames.

Jonas Fogh is a Danish photographer and cinematographer based in Copenhagen.

Klaus Langelund is a former art director from Denmark now working in both photography and film direction.

At Kazam! Magazine we believe design has the power to change the world. Our stories feature people, projects, and ideas that are shaping a better tomorrow.