What Game Shall We Play Today?

In a 1961 magazine article focused on the exhibition, Mathematica: The World of Numbers…and Beyond, Charles Eames responds to the author’s probing by stating, “Toys are really not as innocent as they look. Toys and games are the preludes to serious ideas.” The quote—justifiably—has taken on a life of its own in the sixty-some years since its publication. With a quintessential wink, those nine words that comprise the second sentence offer one of the clearest and most powerful distillations of the Eameses’ design philosophy ever to be put into print.

On the one hand, the statement resonates because there is something so undeniably fun about the world the Eameses carved out in their decades of partnership: plywood elephants, masks on trees, picnics in the meadow, animatronic puppet shows, films about trains and tops, Hollywood connections, cakes, kites, the circus. On the other, the Eameses’ world is also undeniably serious: museum exhibitions and competitions, powerful corporate and civic clients, exhaustive prototyping, encyclopedic research, technical mastery, an unimpeachable commitment to quality. That all of this can be true at once, and that these seemingly disparate sides of the story may in fact relate deeply to one another, is the key to the wondrous dance that bolsters the designers’ near mythological status.

In his memoir Business as Unusual, former Herman Miller CEO Hugh De Pree reinforces the spirit of this duality by recounting a 1954 meeting at the Eames Office that turned into an all-night filmmaking session. “For two or three hours we wound up little toys, running them through these tiny make-believe bushes and trees; because Charles wanted to know which way they were likely to go,” writes De Pree. “Finally, Charles was ready to run some film. Billy Wilder had a car and a motorcycle. I had a car and a bird. The cars had to be run through exactly right, and I had to swoop the bird through the scene at just the right time and place, so that my fingers didn’t show on the film. We did that until three or four in the morning. By that time Charles had shot no more than fifty feet of film. It was an exhausting experience—exhausting but exhilarating. I learned that night that it was important to care, it was important to be concerned about what you were doing, that the details were vital. I learned about quality. I learned about excellence.”

Started in 1966, but not completed until 1969, the film Tops offers a visual celebration of the ubiquitous spinning toys. Here Charles and staff member Alex Funke capture one of the film’s 123 featured tops in motion.

© Eames Office, LLC

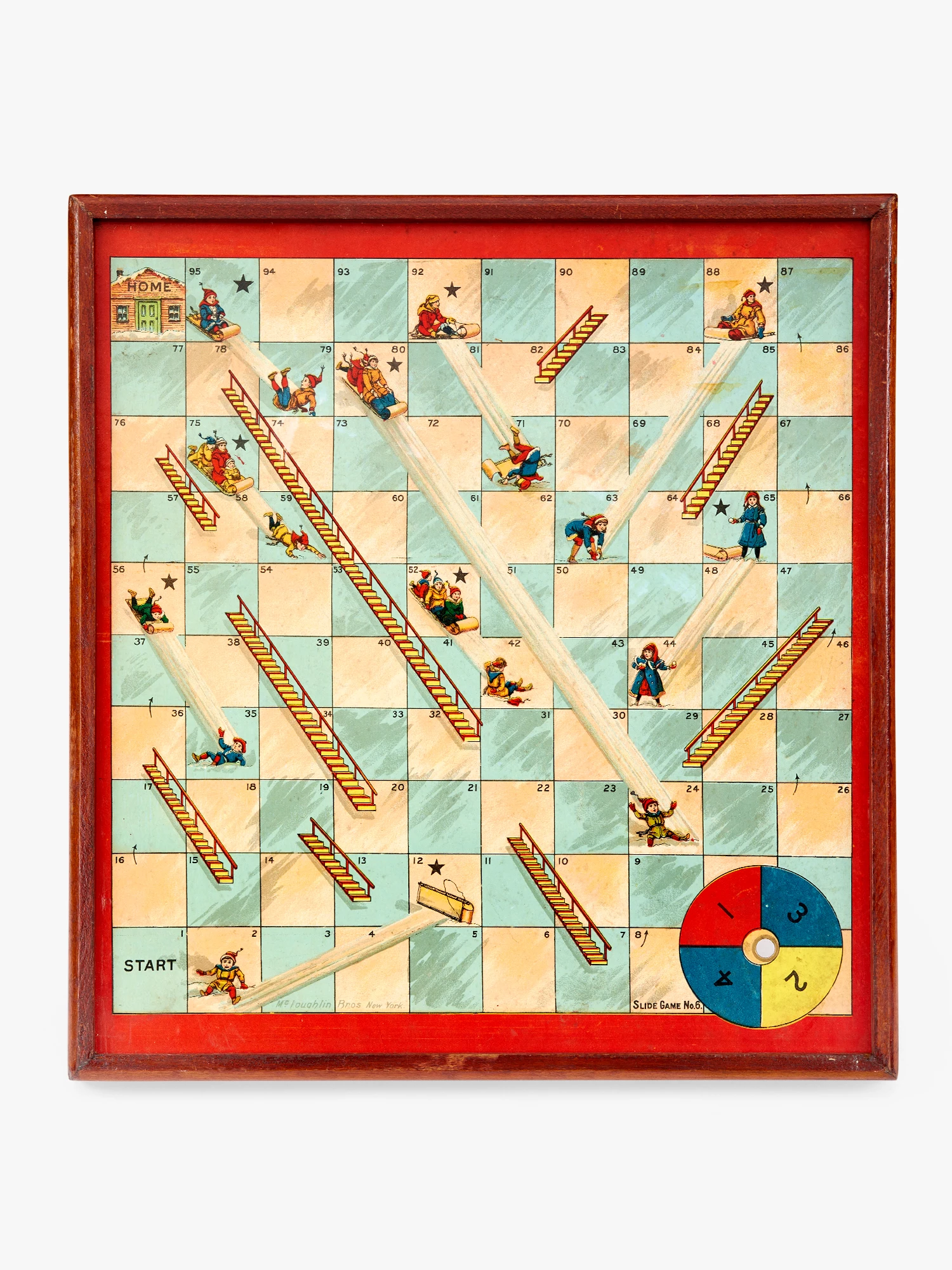

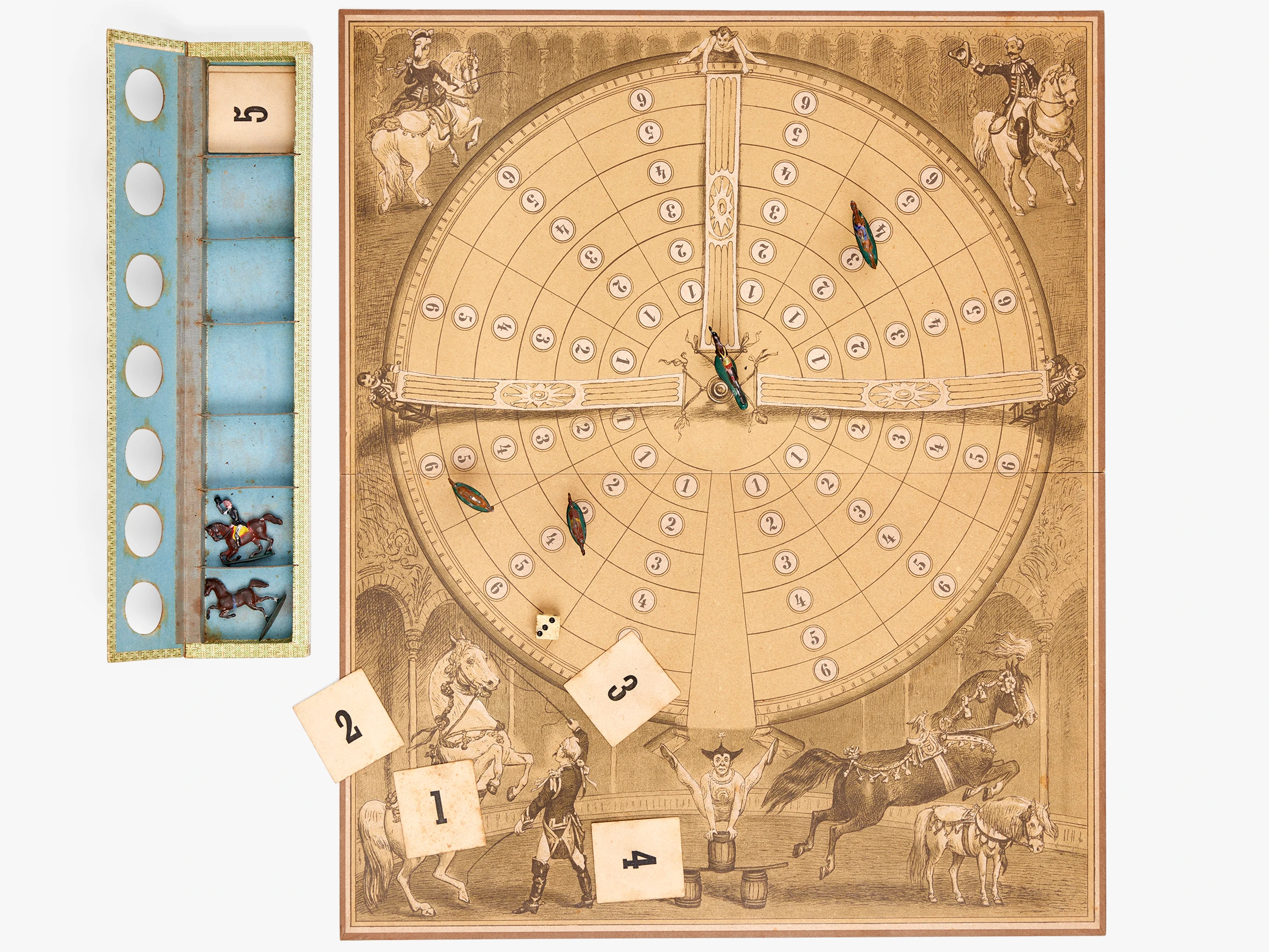

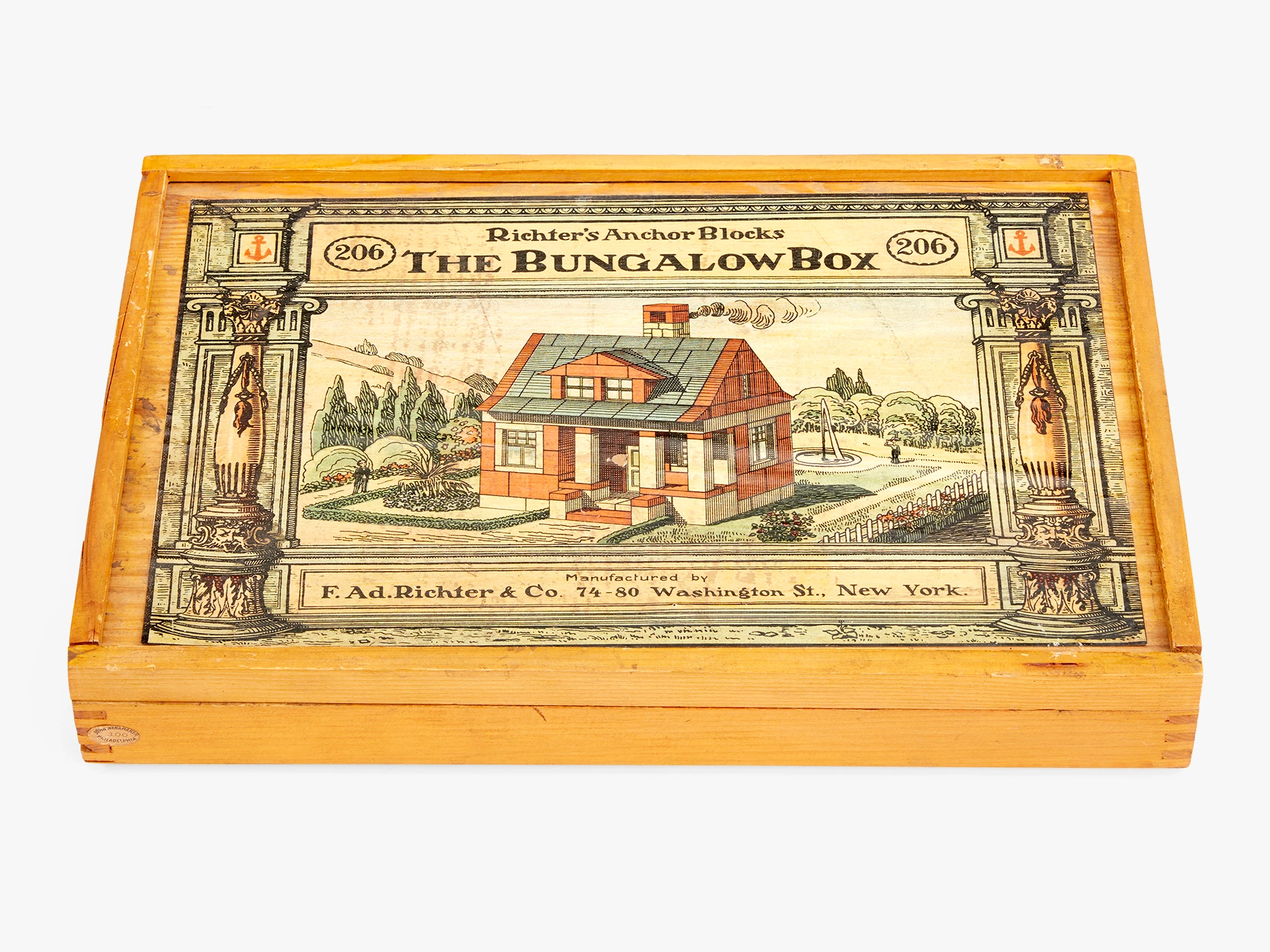

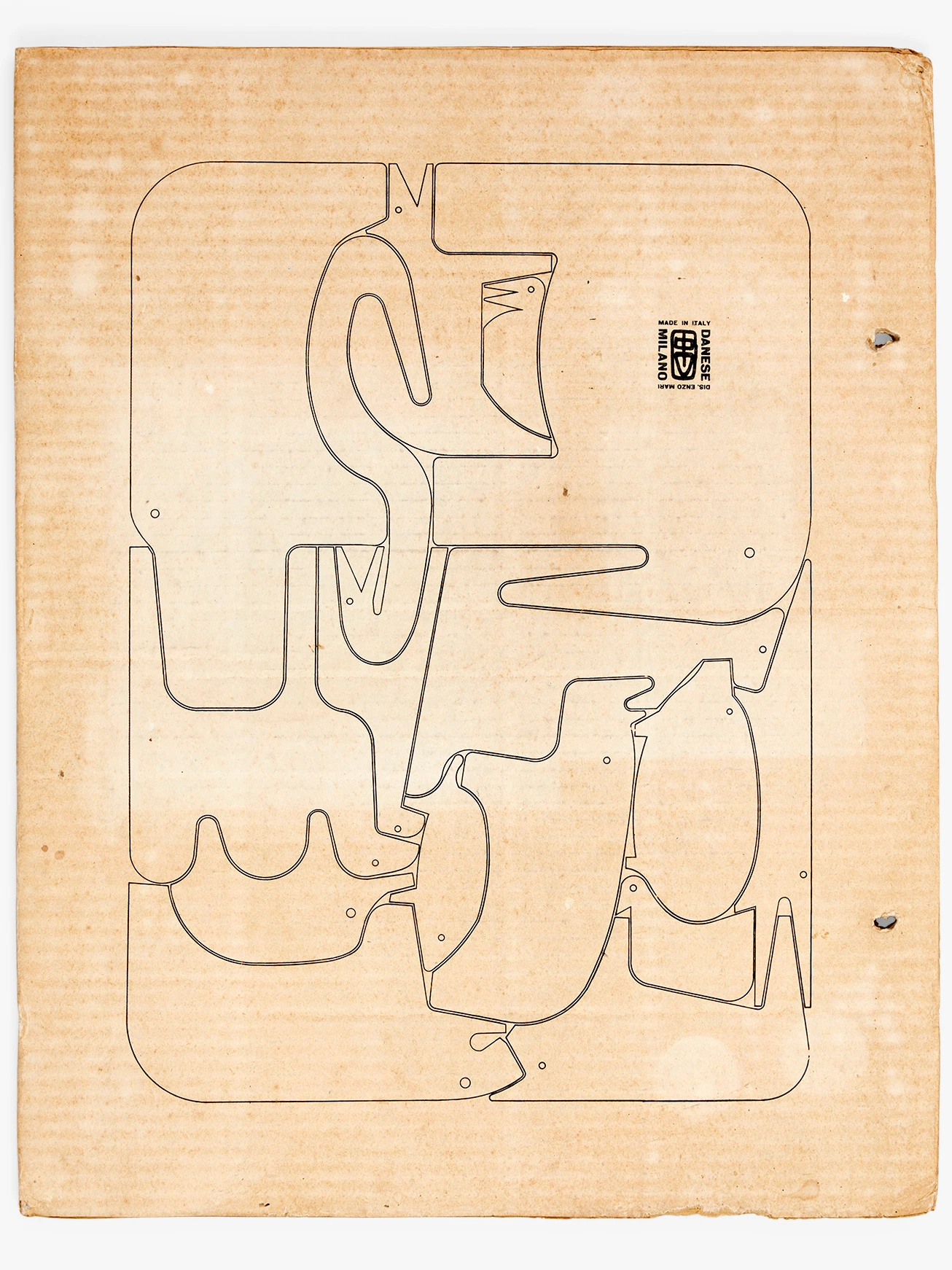

While the classic toys the Eameses favored and employed in films like the one De Pree helped make seemingly have little in common with the couple’s trailblazing designs, to Ray and Charles they were both highly evocative and instructive. Unlike the bulk of mass-market commercial products, and even other contemporary designs by their peers, these toys offered examples of design that were free from self-expression, self-consciousness, and pretensions on the part of the maker. This sort of anonymity was, in the eyes of the Eameses, the paragon of “good design.” Additionally, to be successful in carrying out their purpose as toys, they also had to be deeply imbued with the spirit of what they were setting out to represent or be. Everything about a toy train must contribute to its “train-ness;” a boat its “boat-ness.” This holistic relating—in which every functional and aesthetic decision further contributes to the thing-ness of the thing, to its essence or purpose—is quintessential Eames. Charles would further spell out their design philosophy when he said, “The marvelous part about a kite problem is that this is one area in which one can definitely judge its success or

In their lifetime, the Eameses accumulated hundreds, if not thousands, of such

But the toys also fed their intellect. Analysis—across types, cultures, dates, materials, production techniques, ornament—imposes a different layer of understanding by placing the toy within a broader continuum. The learnings that emerge not only contribute to a more robust comprehension of each individual item, but also the broader categories and connections within which it is situated. The Eameses operated in an era of rapidly expanding multiculturalism and global connection. In toys and their archetypes they saw common threads that rose above cultural or political divisions to contribute to a more universal image of humankind.

In a 1973 Progressive Architecture article, the Eameses’ friend and author Esther McCoy eloquently captures the ethos behind the couple’s consumptive habits. “

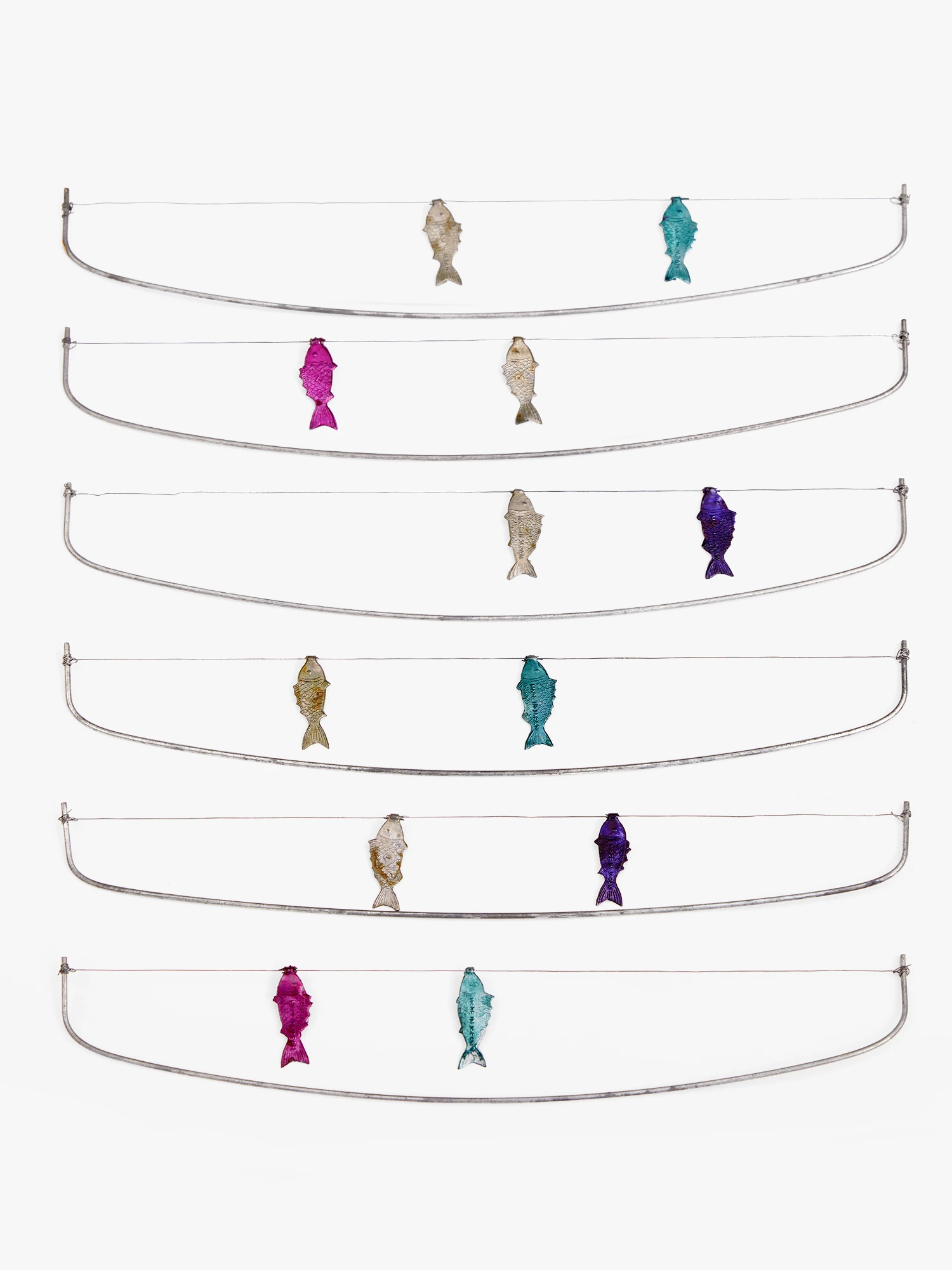

“New York” Toy Boat

View the artifact

Toys are, generically speaking, the tools that facilitate play, and each toy offers an intrinsic link to the actions (and reactions) it inspires or generates. Through play humans begin to satisfy curiosities, acquire knowledge, and build skills—to become, as McCoy says, informed. It’s no surprise then, given how much of their work was dedicated to sharing and building knowledge (often in unprecedented, counterintuitive ways) that the Eameses loved toys, and the play they inspired, with such fervor. It’s telling that when faced with a novel technology like solar power, the designers deduced that a toy (in the form of the Solar Do-Nothing Machine) would be the optimal way to convey its potential.

In one of his 1953 Berkeley lectures Charles prototyped the notion of toys and games leading to serious ideas. He states that “not having lived long enough, children are naturally uninhibited and see everything as new and interesting; they are observing and associating all the time, and there are great truths in things done unconsciously by children.” But some 20 years later, in Perry Miller Adato’s film An Eames Celebration, he gives the game away. “Toys are not really for children,” he reveals. “Toys are really for adults—especially grandparents.”