By 1950, Charles and Ray Eames had cemented their status among the leading modernist designers of their time and were riding a wave of success. Their office was engaged in a torrent of projects, ranging from furniture design and graphics to architectural commissions and exhibitions—and the duo was exploring ideas for children’s toys and personal film projects. The year prior, the couple had completed and moved into their now iconic Pacific Palisades residence, Case Study House No. 8. The home—an open framework unconstrained by precedents and preconceptions—represented the theme of possibility that Los Angeles offered. For the Eameses, the city was a hothouse of opportunity, the backdrop and sometime catalyst for their work.

Because of Los Angeles’s role as a hub for filmmaking, industry, art, and architecture, the Eameses were continually put in contact with a stream of notables in a variety of fields—connections that fueled their creativity and opened new avenues for exploration. As the Eameses’ stars shone ever brighter, they became prominent fixtures in the landscape of Los Angeles’s creative scene, and leading figures would seek them out as a part of their West Coast itinerary. A momentous connection in the summer of 1950 with the artist Saul Steinberg would result in an extraordinary collaboration—and an ongoing conversation at the spearhead of modernist thought.

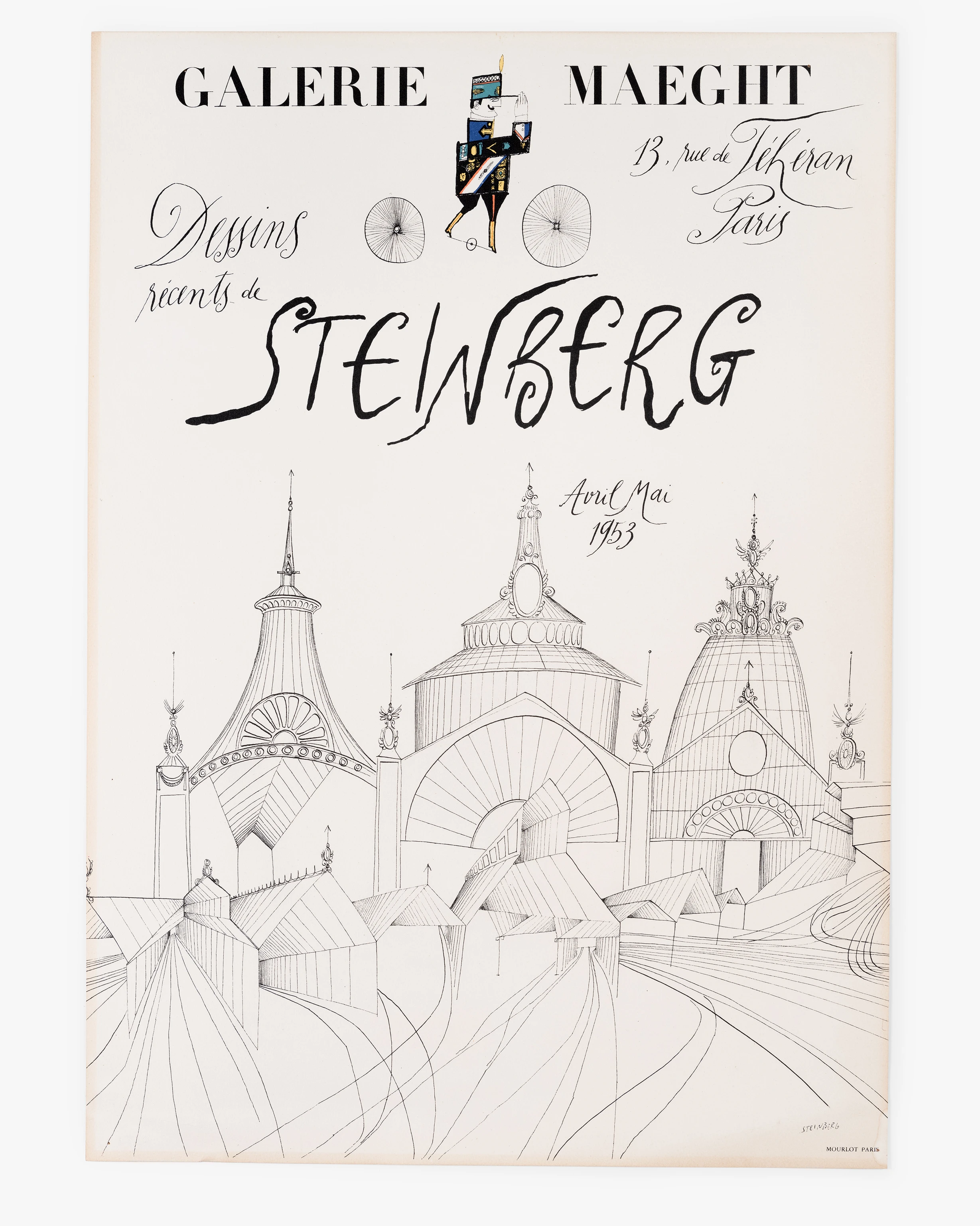

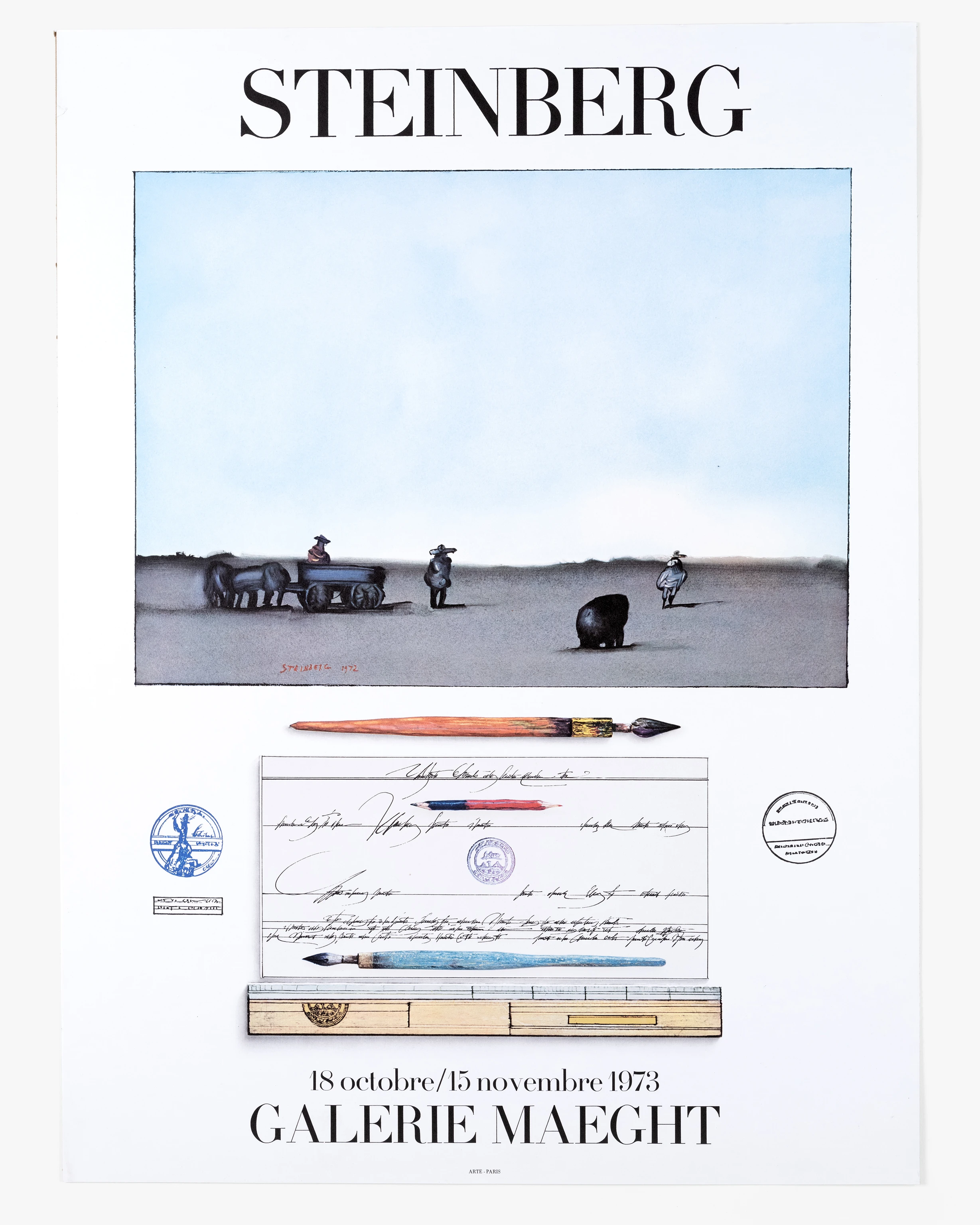

Steinberg, a Romanian émigré and artist, rose to fame in the 1940s through his ability to sharply convey pointed, resonant commentary with an economical visual vocabulary. While still overseas at the outset of the decade, a contact from his days studying architecture in Milan helped to get him magazine jobs from a variety of New York–based publications, and after his arrival stateside, these connections led to a commission in the US Naval Reserve—and eventually citizenship. During the war years Steinberg directed his talents at creating anti-fascist propaganda for the Office of Strategic Services’ division of Morale Operations, while sending dispatches back to The New Yorker from China, India, North Africa, and Italy. In 1946, the same year the Eameses debuted their plywood furniture at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, Steinberg took part in the MoMA exhibition Fourteen Americans, alongside Arshile Gorky, Robert Motherwell, and Isamu Noguchi among others. As his oeuvre expanded beyond the world of commercial commissions, he evolved from a more cartoonish approach to make way for what art historian Ernst H. Gombrich would define as the “philosophy of representation.”

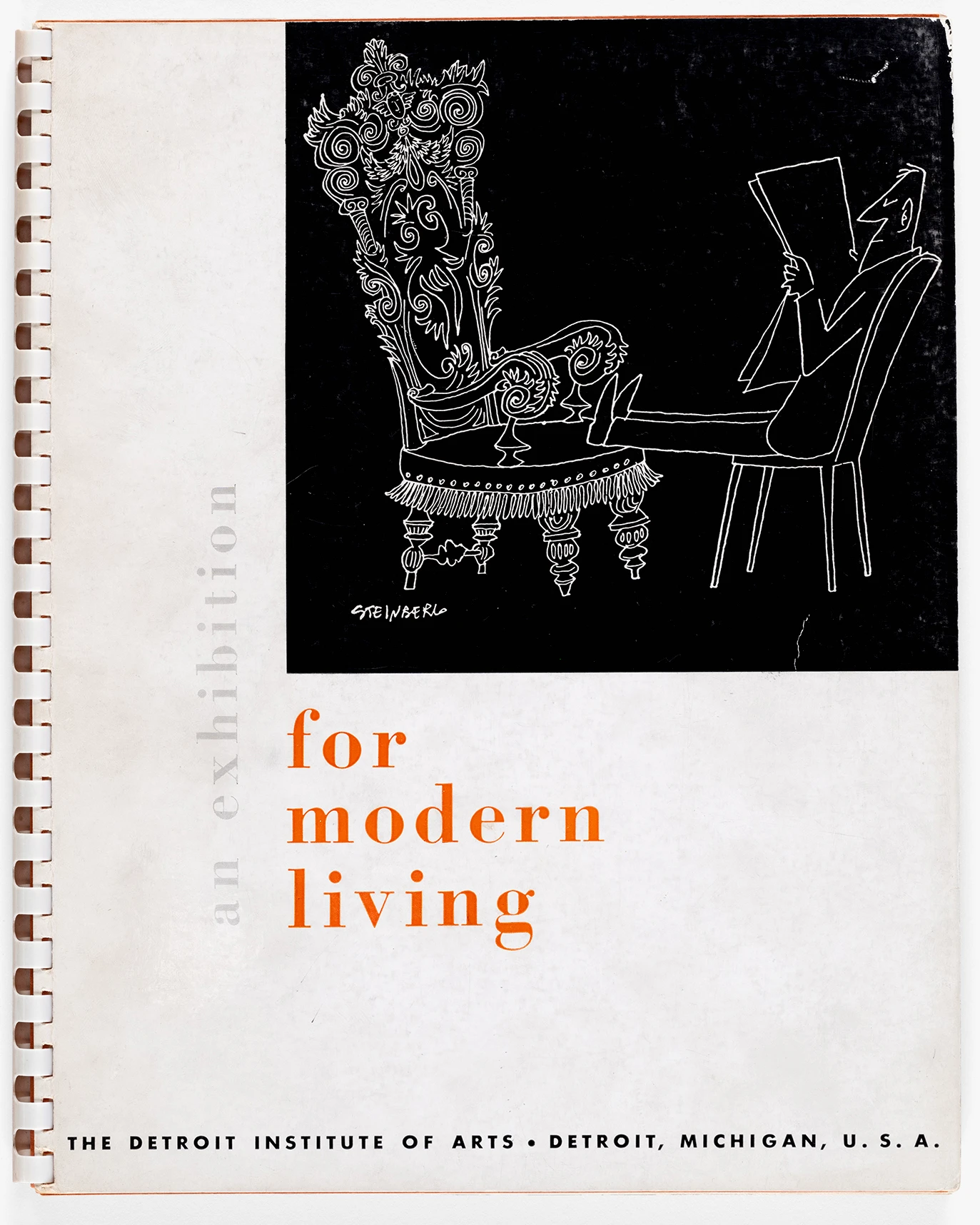

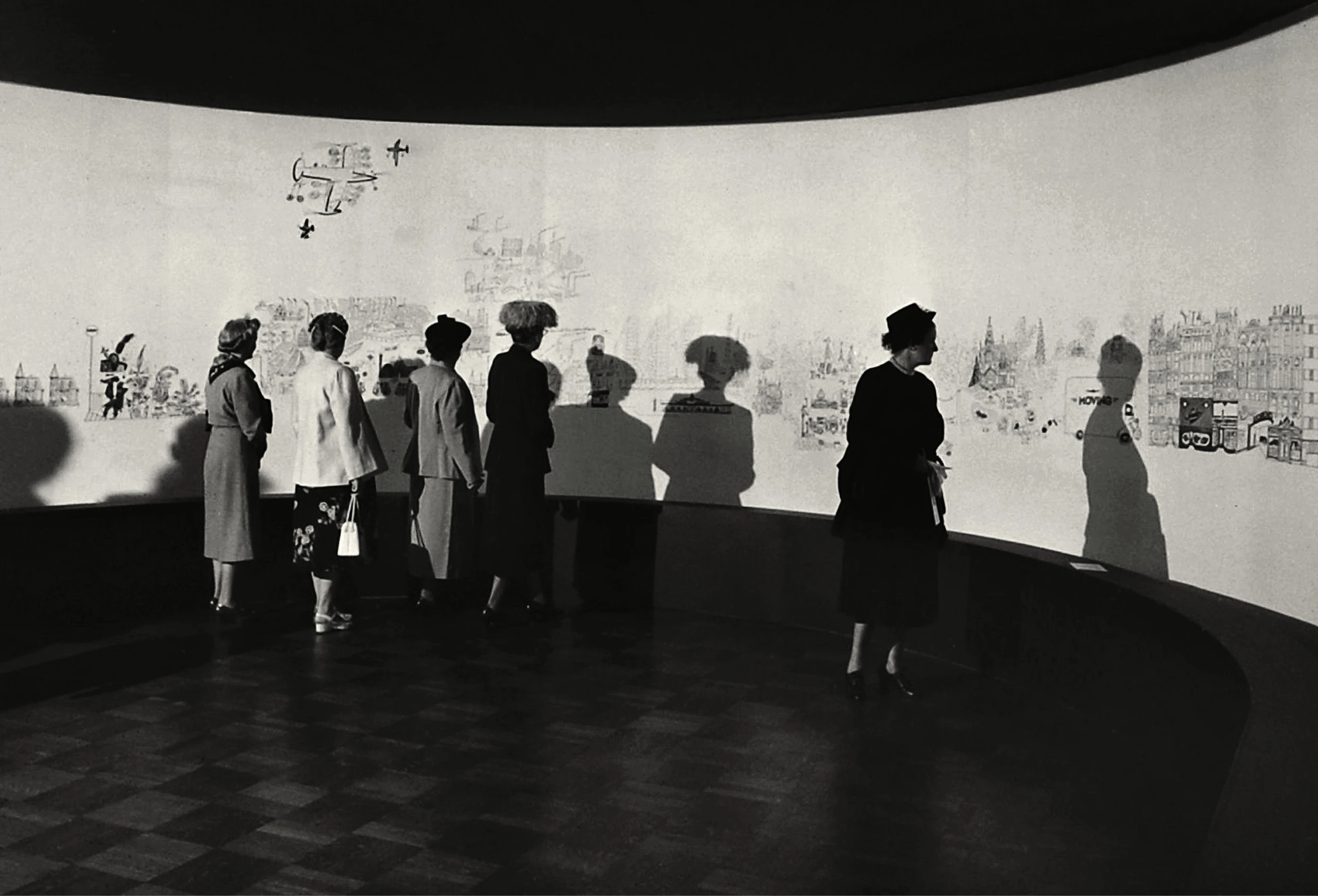

At Alexander Girard’s behest, 24 Steinberg drawings were photographically enlarged and assembled into a mural of Detroit that served as a transition between the past and present within the exhibit.

Wallace Kirkland / The LIFE Picture Collection / Shutterstock.

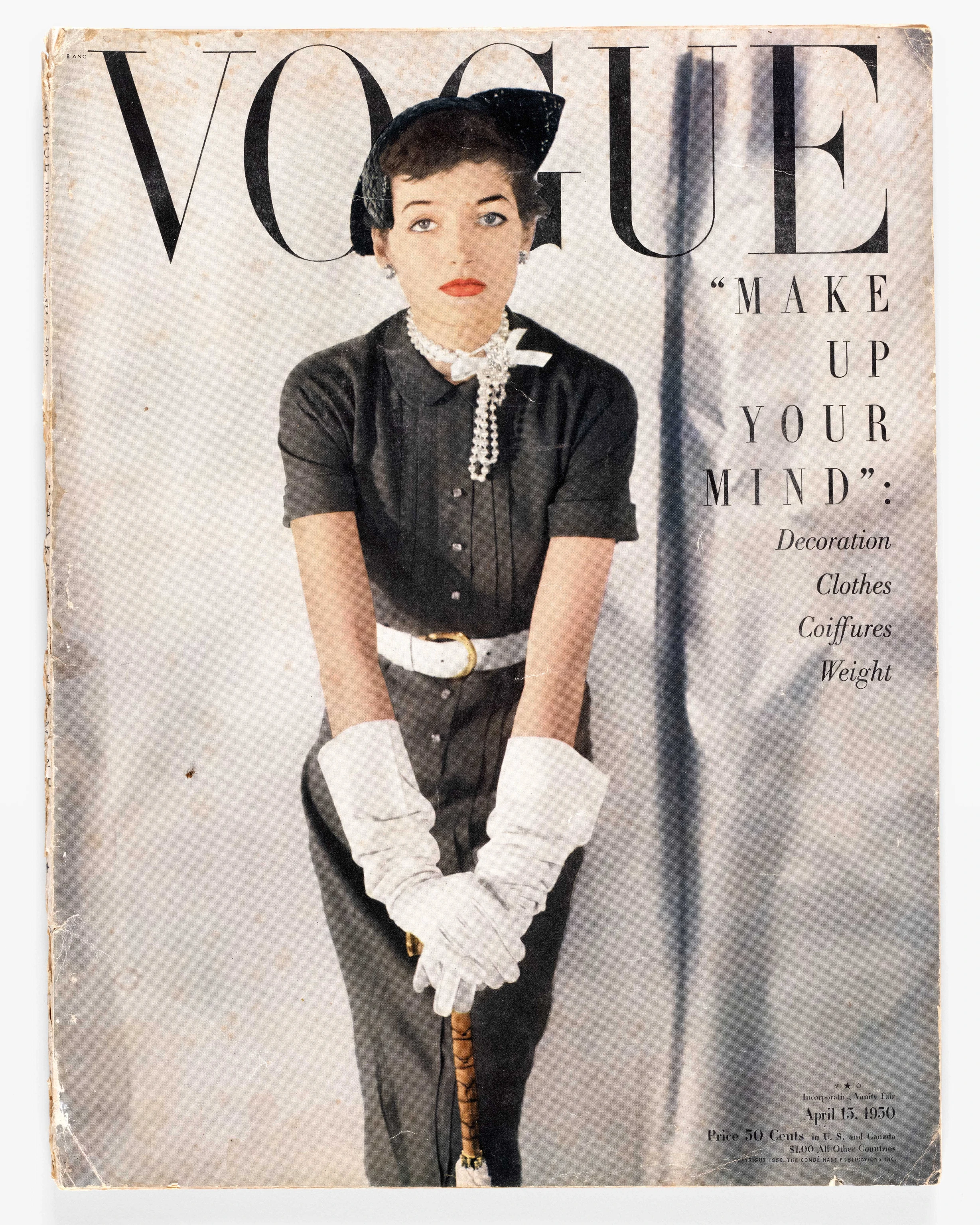

By the latter half of the decade, thanks largely to his New Yorker placements, Steinberg was widely known and had become a fixture of New York’s intellectual and artistic circles. His services were wildly in demand, and seemingly no subject matter was beyond reproach. The February 1947 issue of Interiors magazine, offers “Furniture News from France by Steinberg, humoriste Américain” in the form of a series of drawings of ornate, highly decorated chairs drawn over hotel letterhead and casino ledgers. The article also includes the first incidental reference to the Eameses within Steinberg’s orbit: the author notes that “the man who so lovingly retraces the scrolls and fringes and mad ornaments of our artistic heritage, does not relish them in his own house,” and instead “put through an order for half a dozen Eames chairs.” As a “chronicler of the absurd,” Steinberg was ever-observant of America’s changing cultural landscape and seemed to delight in the widening gulf between popular tastes and the vanguard of modernist art and design.

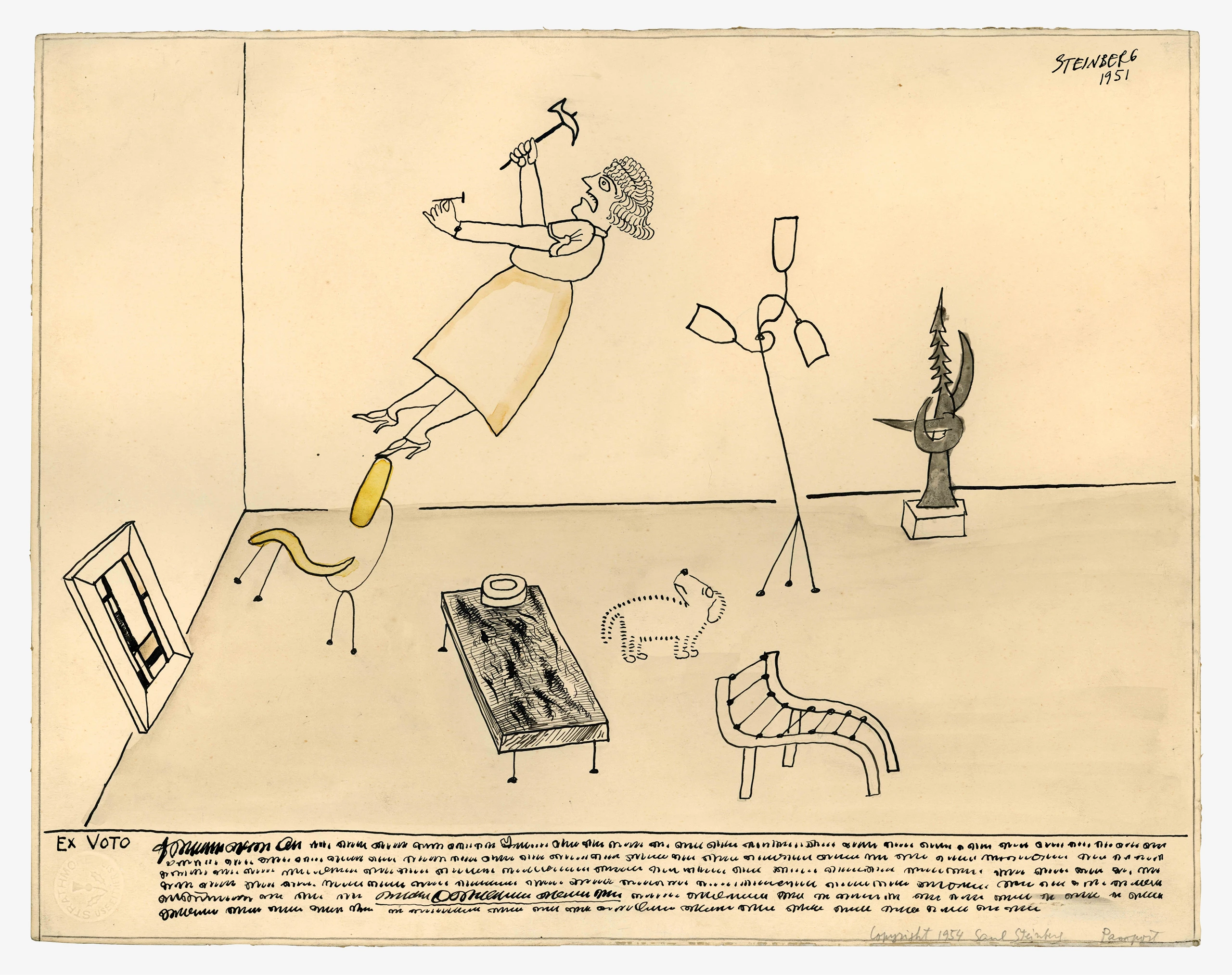

These impulses were on full display in his 1949 publication, The Art of Living, where the emphasis turns to the built environment and the trappings of modern existence in post-war America. Within the first few pages an Eames molded plywood chair makes its appearance, with an antimacassar covering the chair’s back. A comic rebuttal to the design’s lack of ornamentation or sentimentality, Steinberg seems to at once be skewering both those who would find the Eames chair insufficient in its pure state as well as the modernists’ break from tradition.

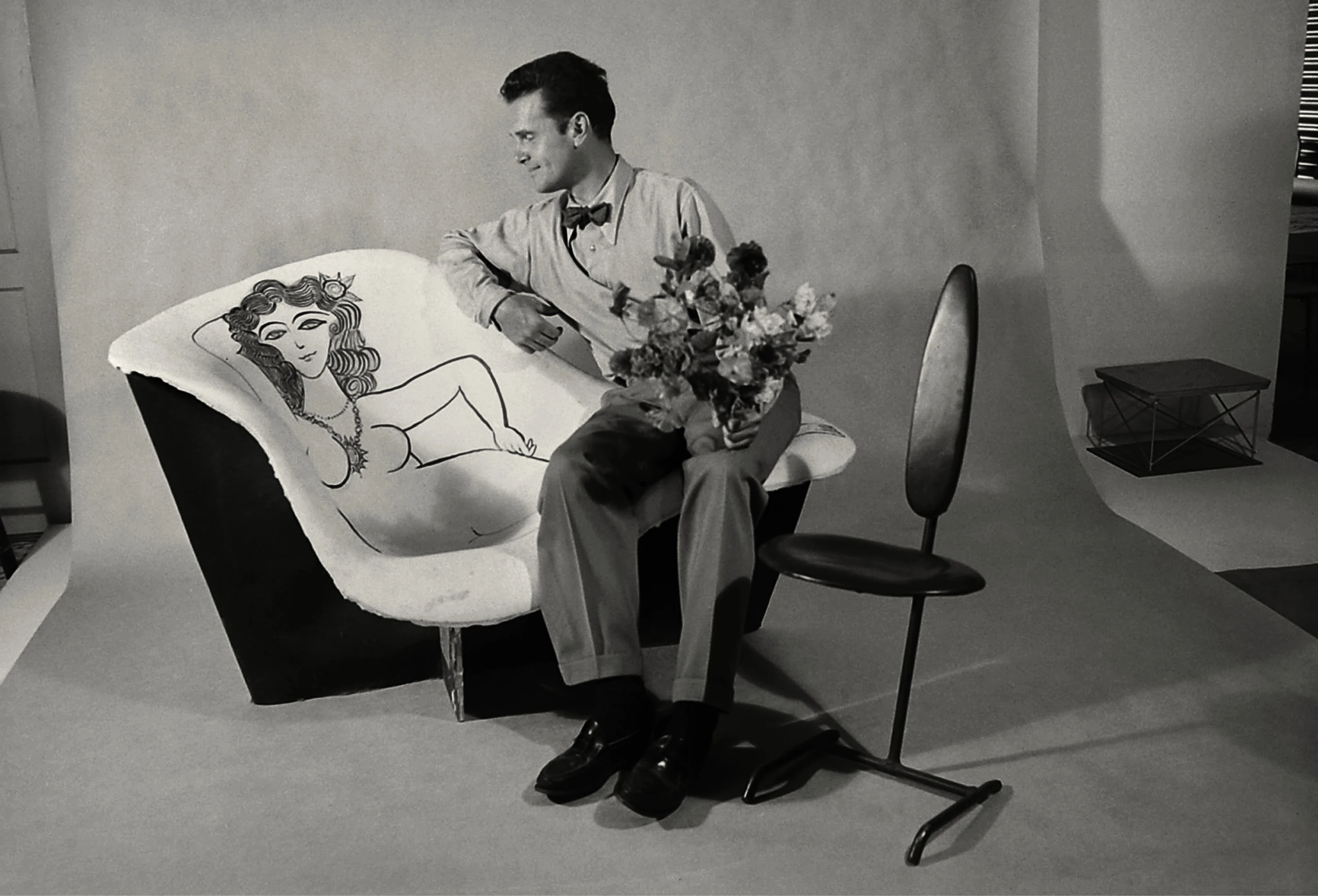

Charles playfully woos a Steinberg nude painted onto a mold of the La Chaise. Both the La Chaise and Minimum Chair to Charles’s left were entered into MoMA’s International Competition for Low-Cost Furniture Design.

Peter Stackpole / The LIFE Picture Collection / Shutterstock

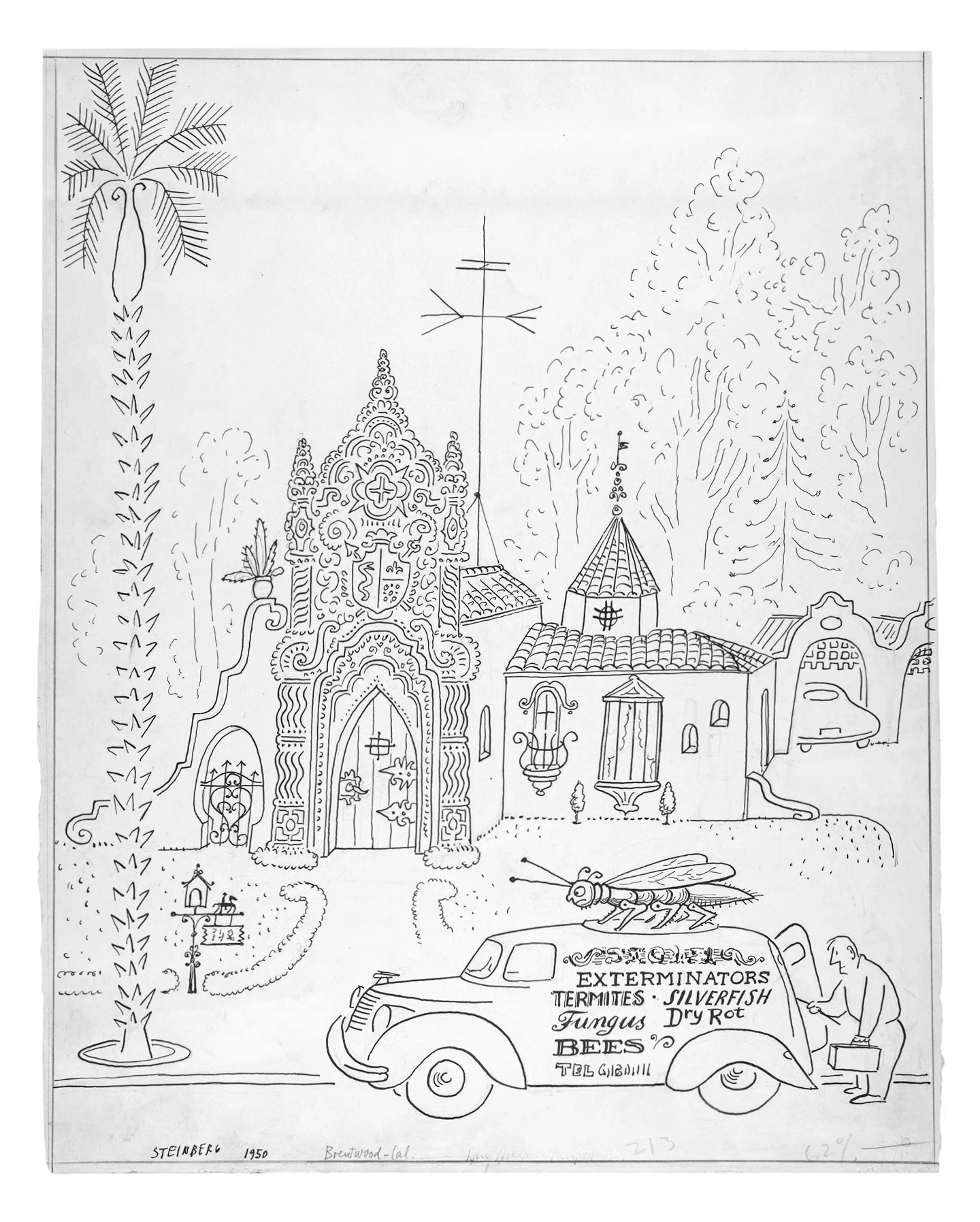

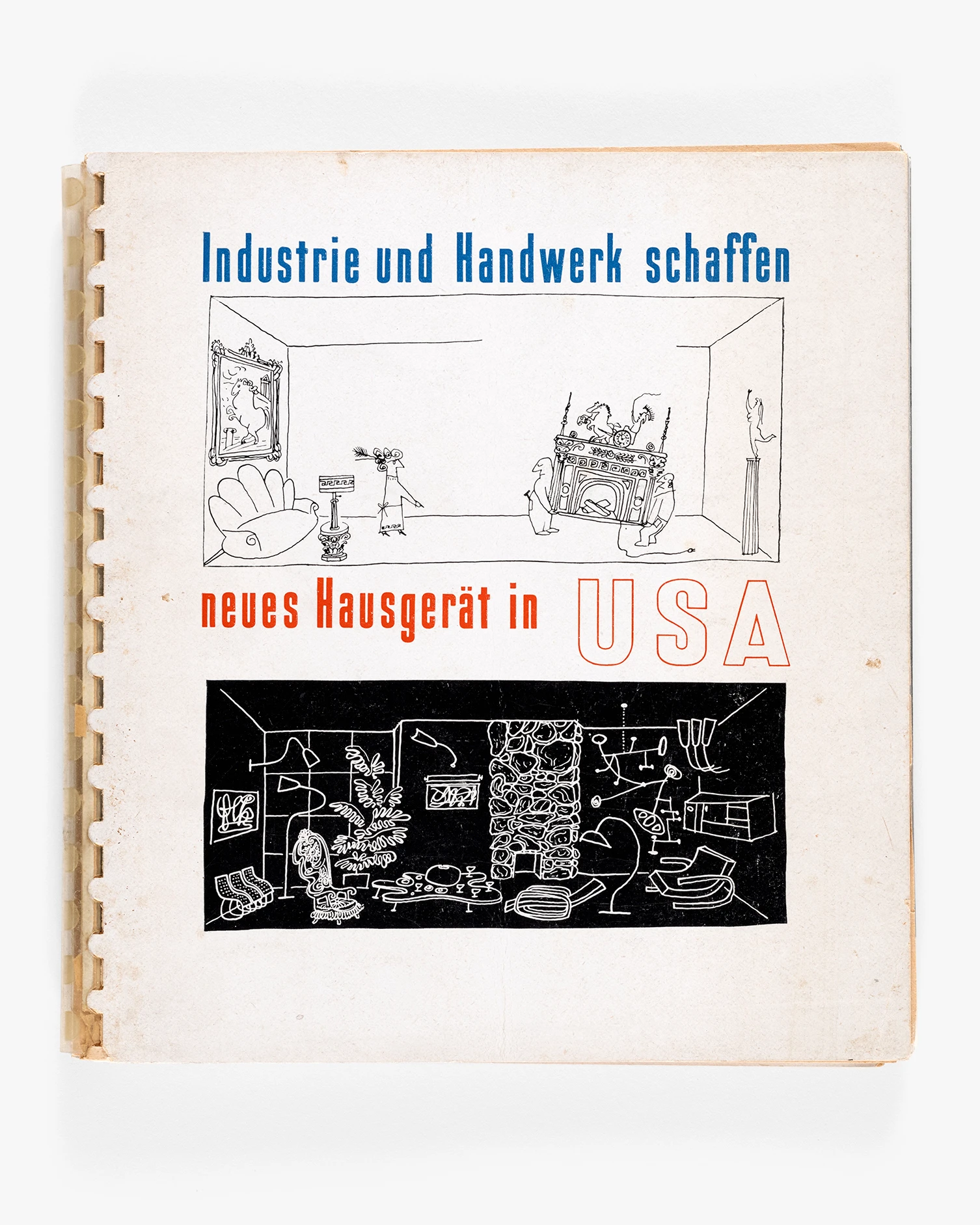

Later in the same year, the same drawing was reproduced in the catalog for Alexander Girard’s groundbreaking An Exhibition for Modern Living, held at the Detroit Institute of Arts. The show, curated and designed by Girard, offered a compelling case for the acceptance of modern design, not as a style du jour, but rather as a way of living.

The following year, Steinberg traveled to Los Angeles with his wife, the artist Hedda Sterne, for an unusual, but potentially promising assignment: to play a “painting body double” in an upcoming MGM production. “

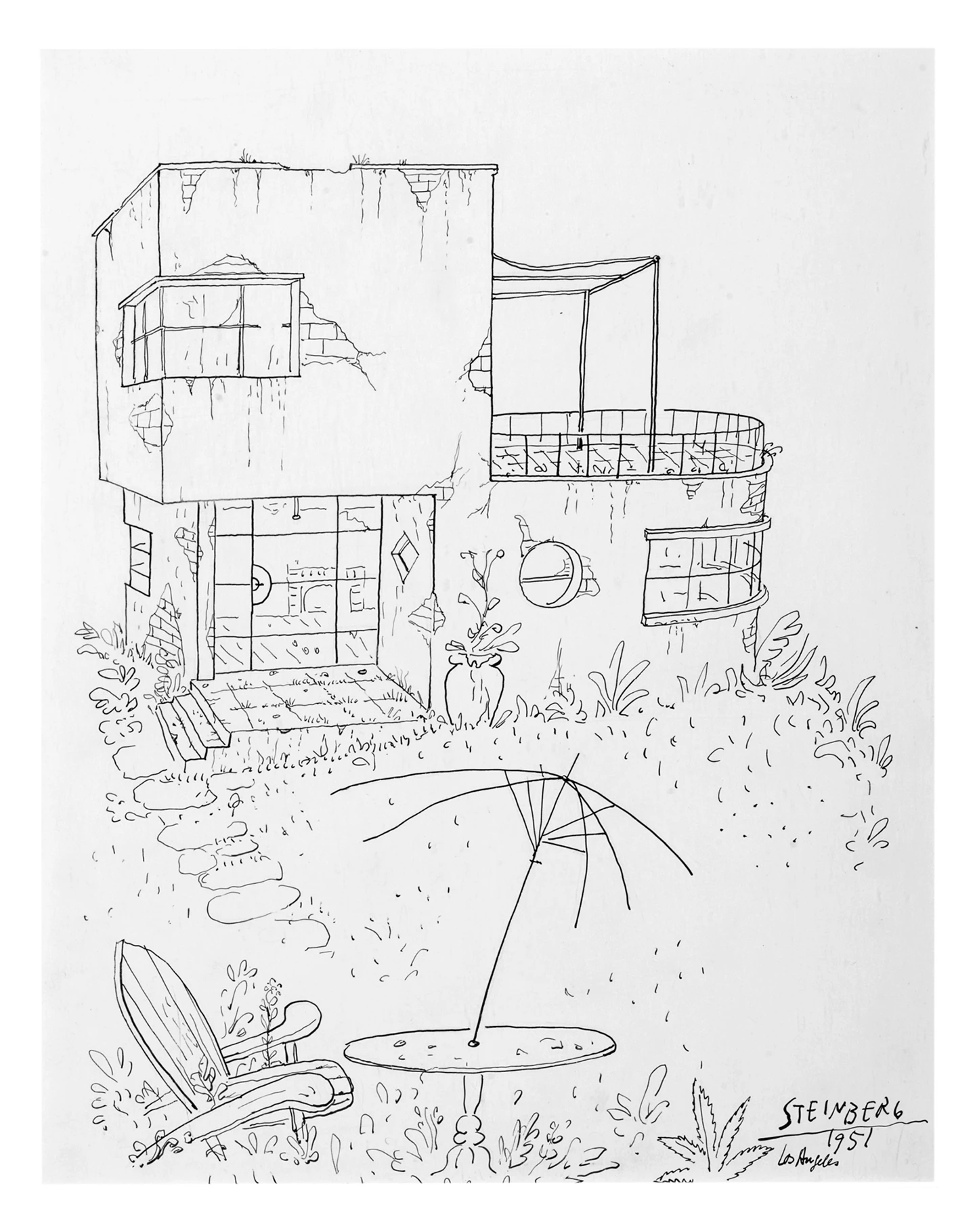

Freed from his contractual responsibilities, Steinberg quickly took up with Hollywood’s cast of European émigrés, including Christopher Isherwood, Igor Stravinsky and (well-documented friend of the Eameses) Billy Wilder, and attempted to capture something of the bewildering milieu offered by the emergent metropolis. “It was the first time I had seen a highway city, which was to be the model for the rest of our cities. Los Angeles is the avant-garde city of parody in architecture and even in nature (canyons and palm trees). Difficult to draw, a trap—like portraying clowns,” he later wrote. Los Angeles, with its well-known excesses, seemed like a city purpose-built for Steinberg’s critique, but its exaggerated reality meant that he had to “keep making an effort not to fall into clichés,” (as he noted in his published correspondence with Aldo Buzzi). The drawings Steinberg made during this period would later be featured in the January 27, 1951 issue of The New Yorker under the title, “The Coast.”

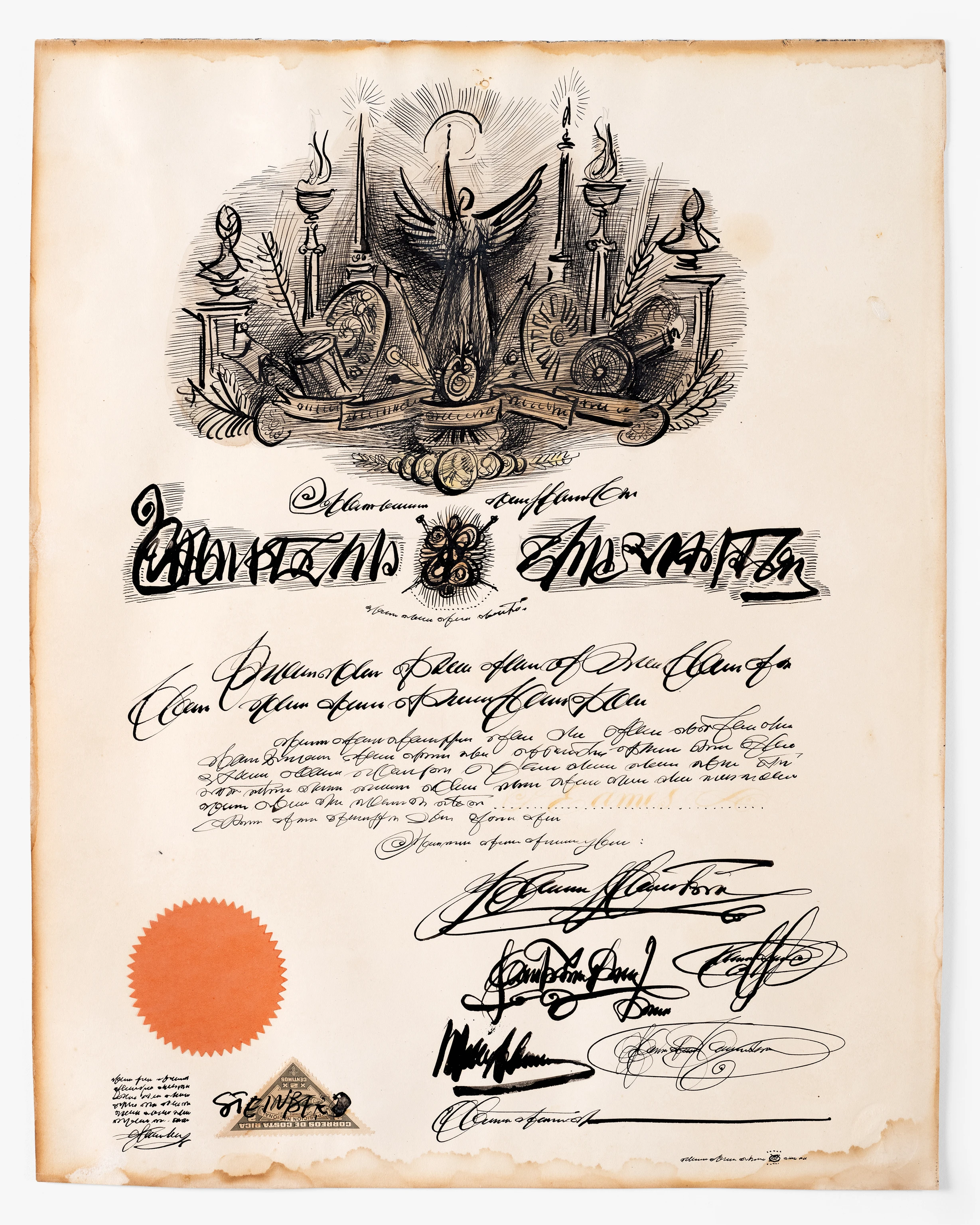

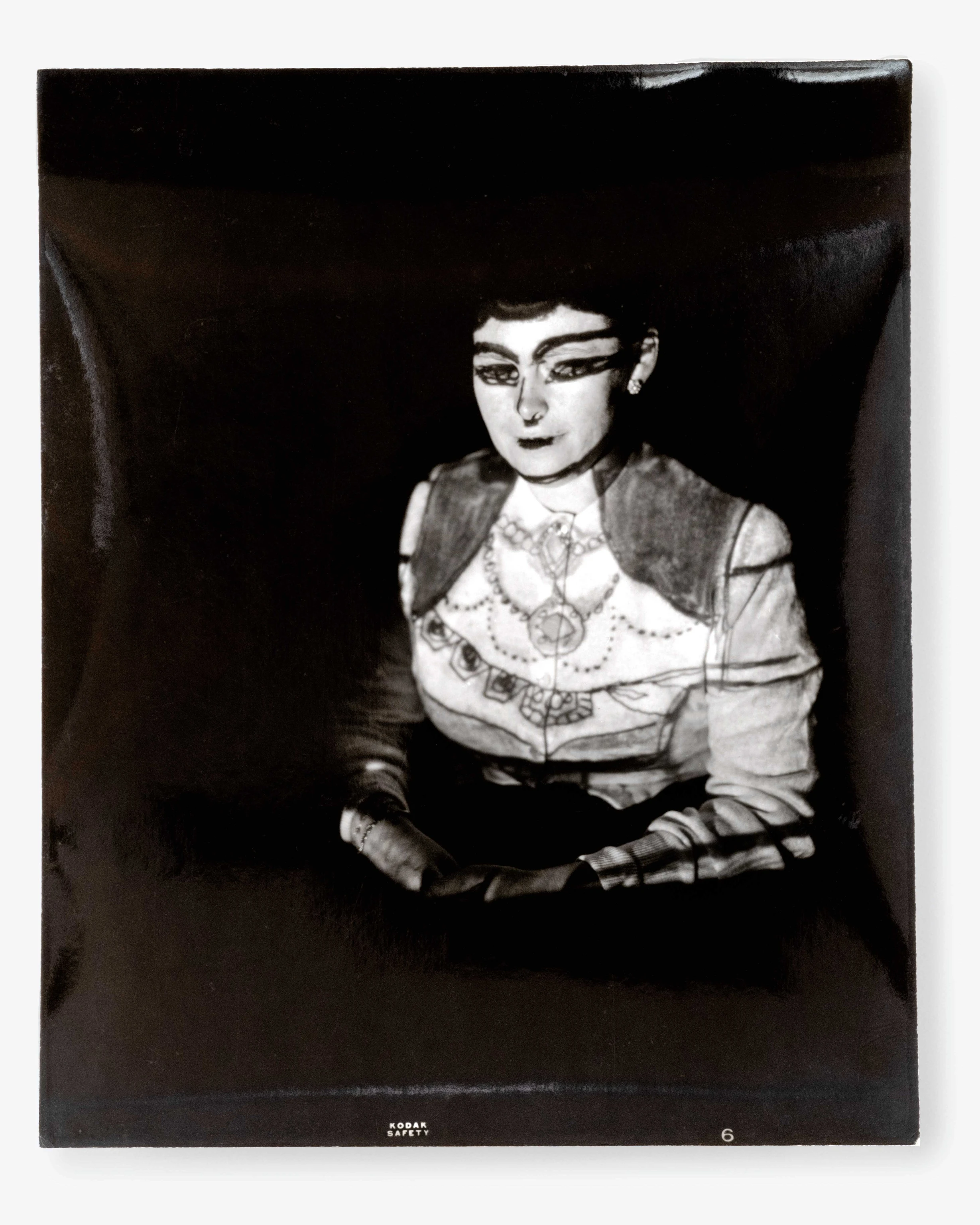

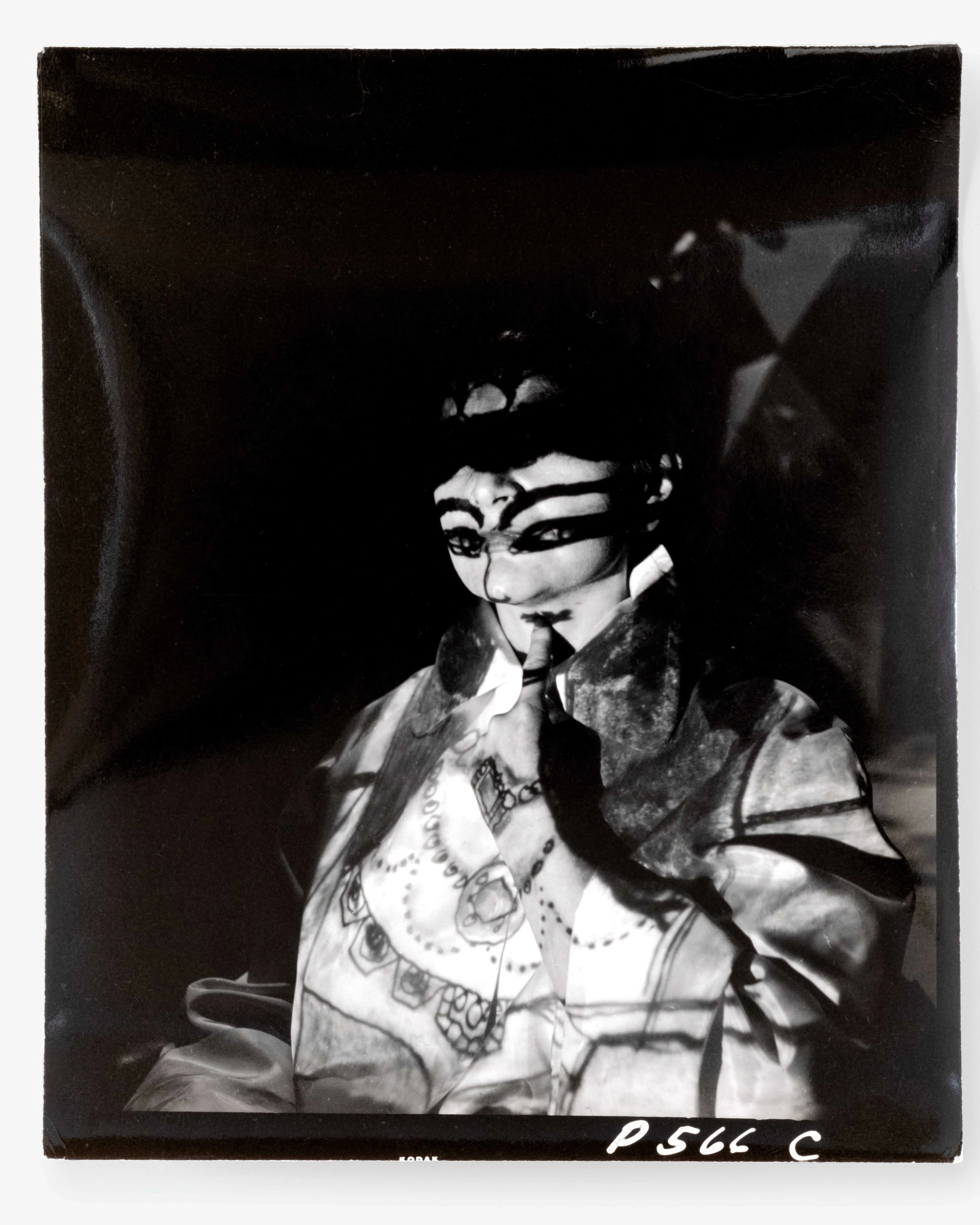

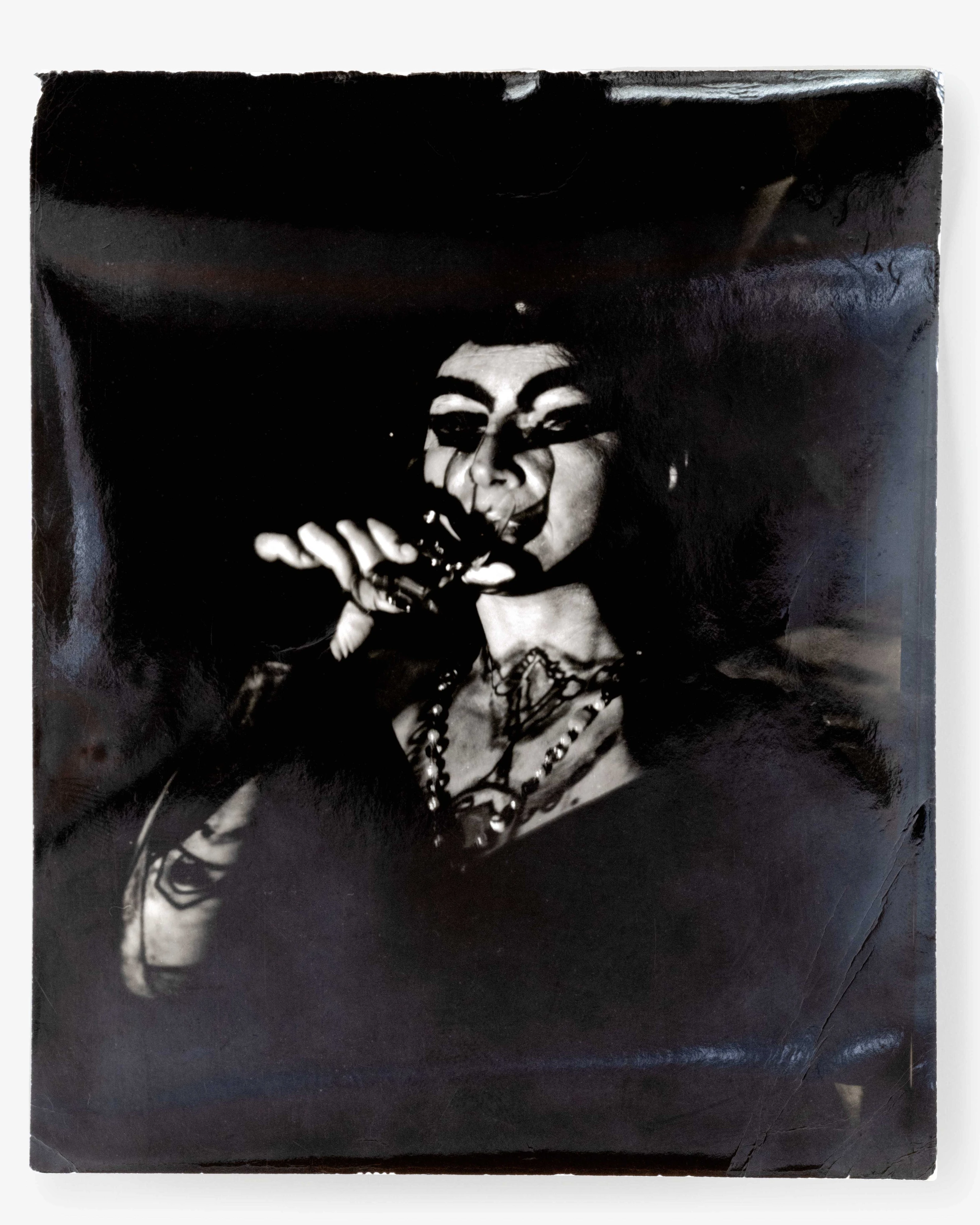

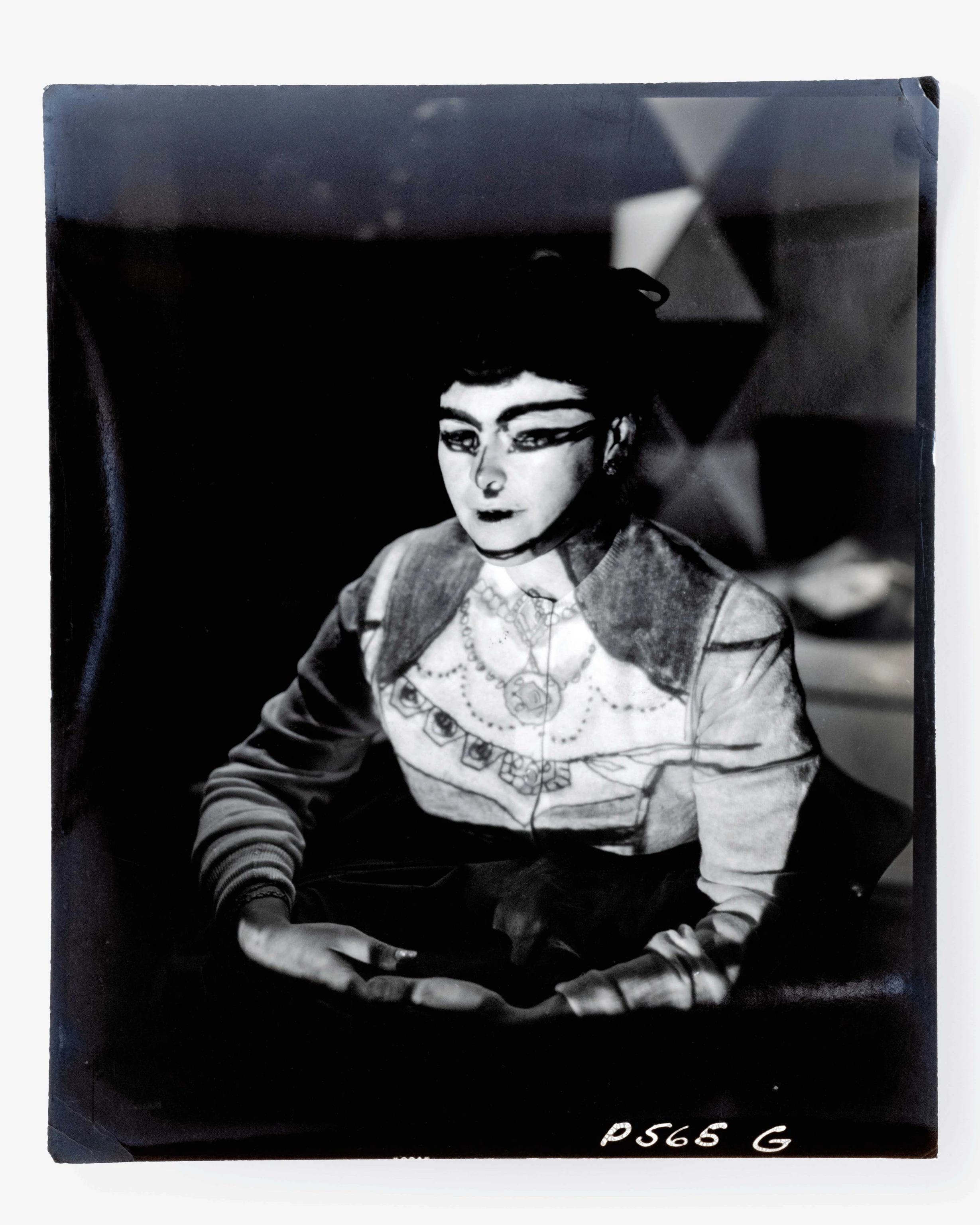

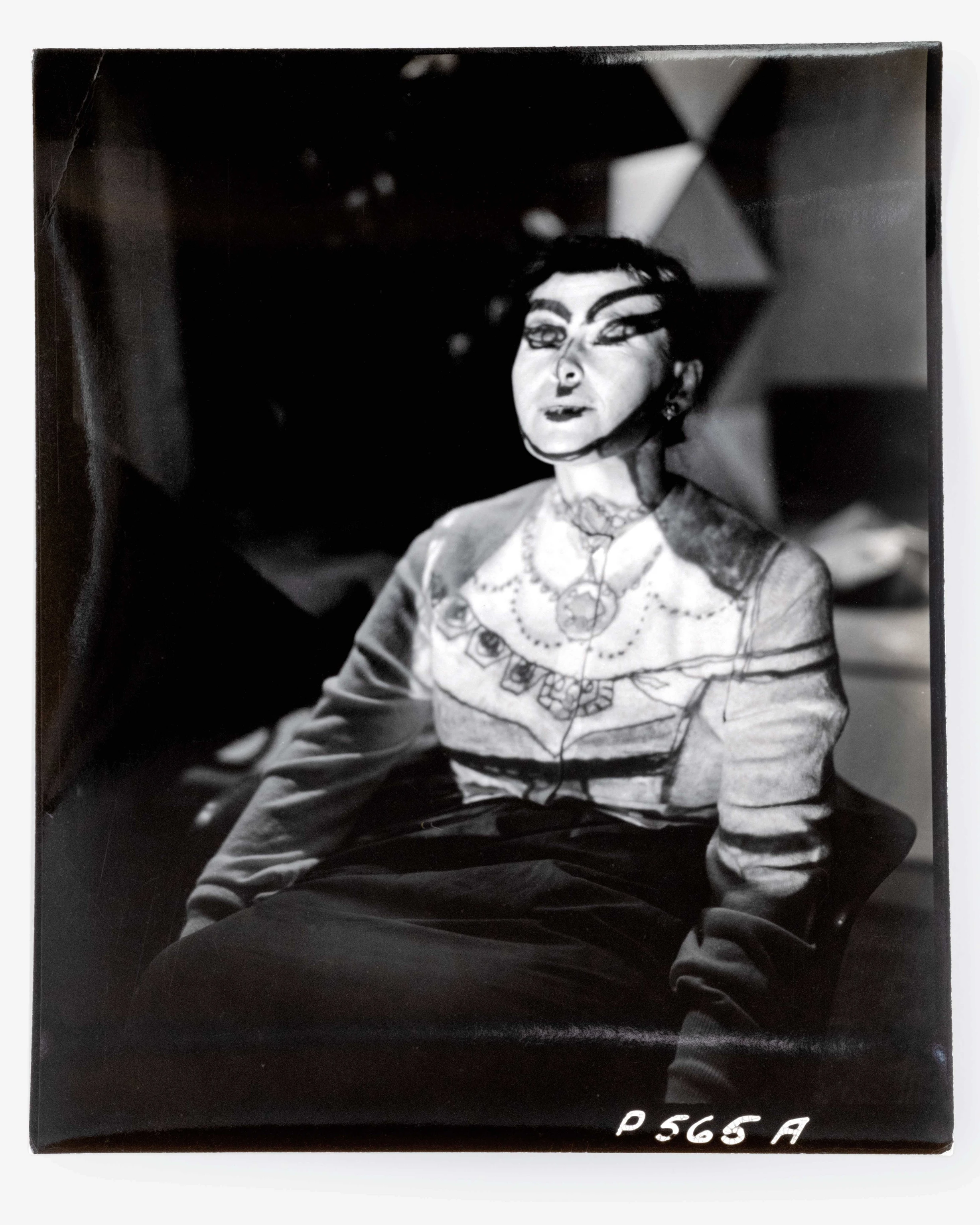

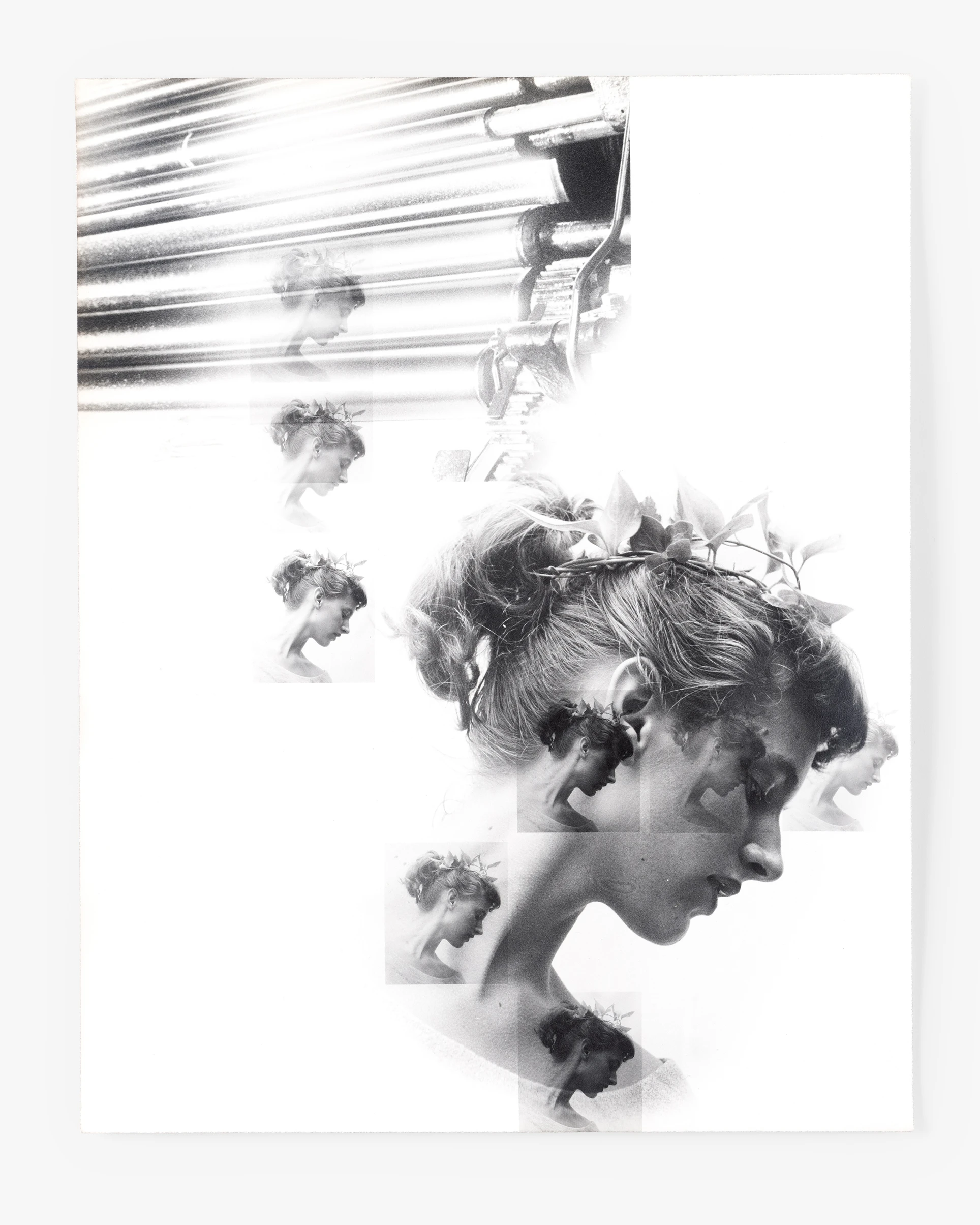

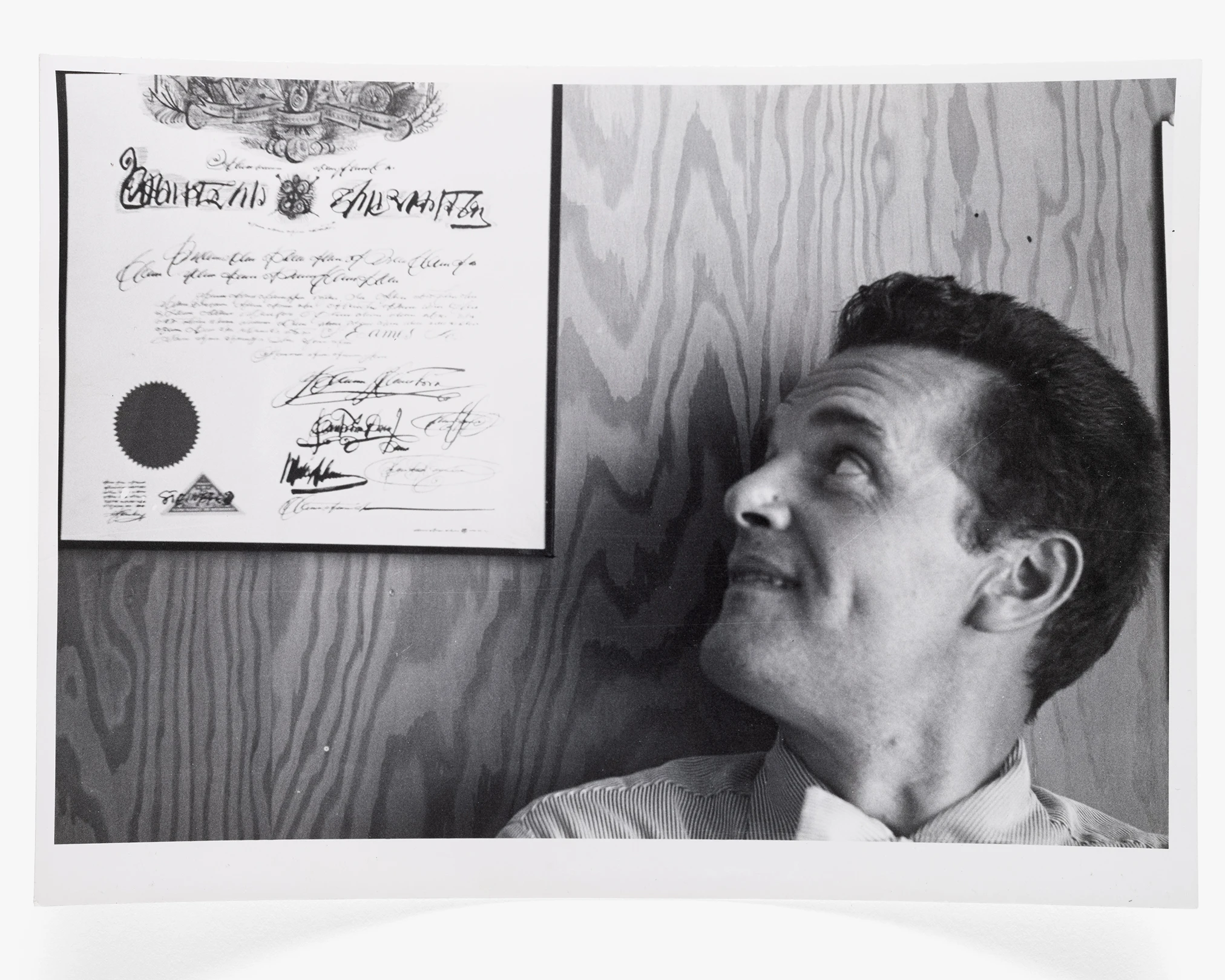

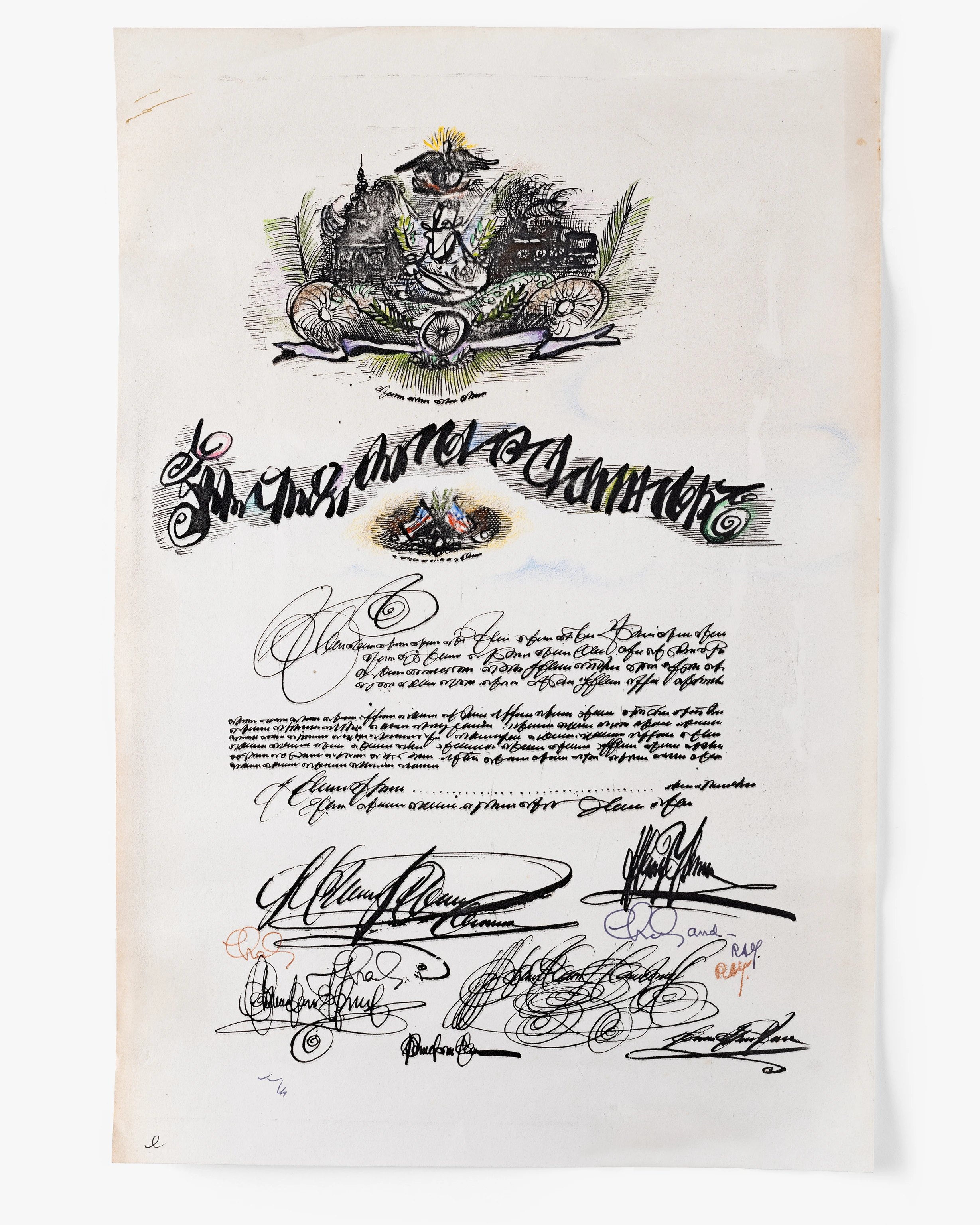

Having previously corresponded through their mutual friend Bernard Rudofsky, the Eameses began to socialize with Steinberg and Sterne shortly after their arrival in the City of Angels. As was often the case for Ray and Charles, the lines between life and work rapidly, and easily, blurred. At the Eames House the couples projected Steinberg’s drawings of women onto Ray and Hedda and then photographed the otherworldly results. Eucalyptus leaves were collected from the meadow to be transformed into birds. They conceived of movies about drawings and Los Angeles. Having noted that Charles Eames never graduated from university or received his degree in architecture, Steinberg rendered a series of elaborate fake diplomas for the erstwhile academician.

While these ephemeral experiments were indicative of the relaxed and playful spirit permeating the proceedings, a visit by Steinberg to the Eames Office in Venice resulted in a series of iconic collaborative works that have withstood the test of time. Within the makeshift photo studio where the Eameses photographed their designs, Steinberg was given free rein to draw on the walls and the furniture itself. An early prototype of the La Chaise offered a canvas for a recumbent female figure—provocatively attired in only a necklace and high heels. A plywood lounge chair was transformed by a nonplussed visage on its back. A freshly minted fiberglass arm shell was reimagined into a nude torso—with her legs outstretched on the floor in front of her. The bucket of another fiberglass arm shell offered the perfect cozy retreat for a cat to curl up within.

Saul Steinberg, Eames Chair, 1951, Ink and watercolor on paper, 11 ½ × 14 ½ in. Artis— Naples, The Baker Museum. Gift of Olga Hirshhorn, 2013.1.186

© The Saul Steinberg Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

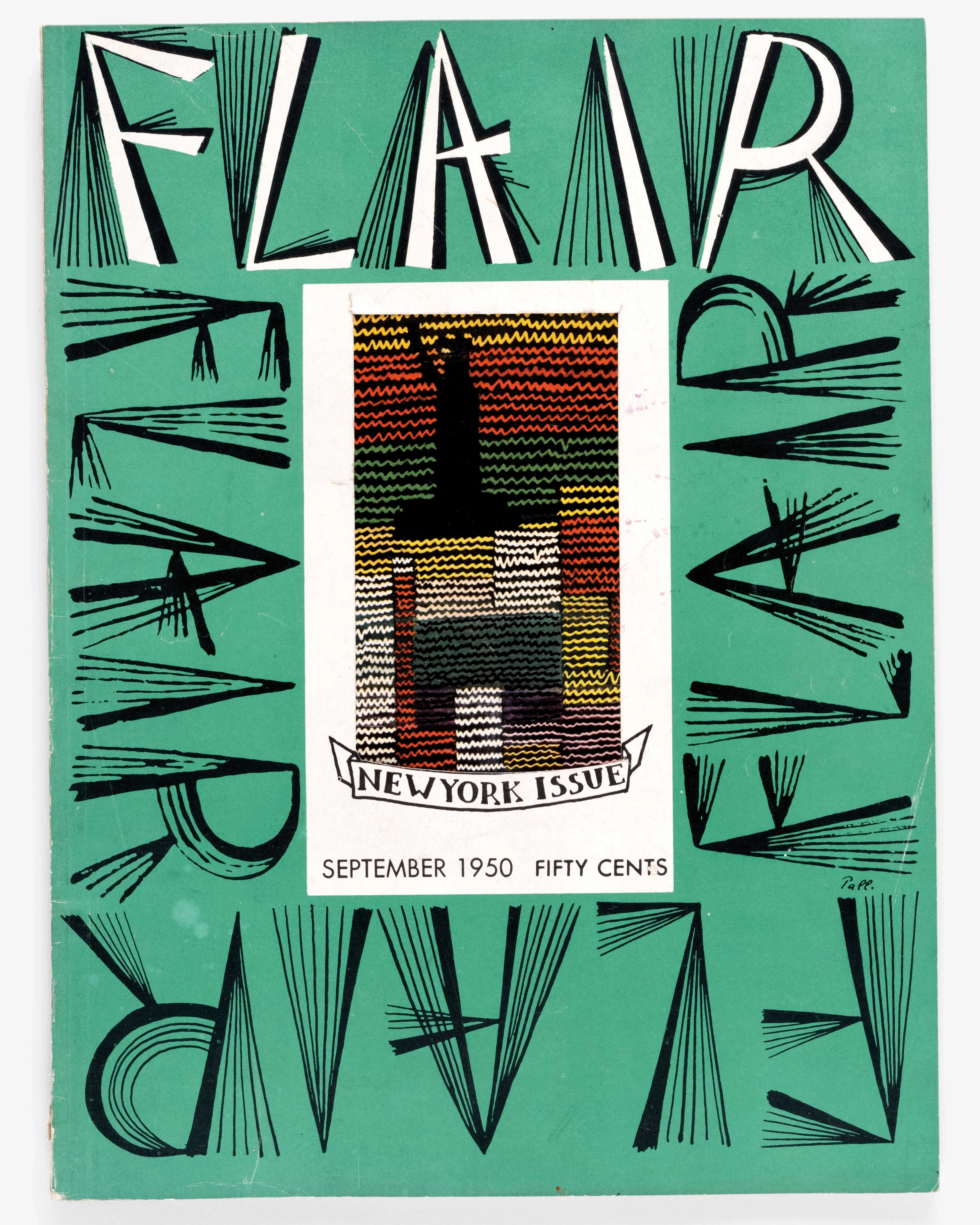

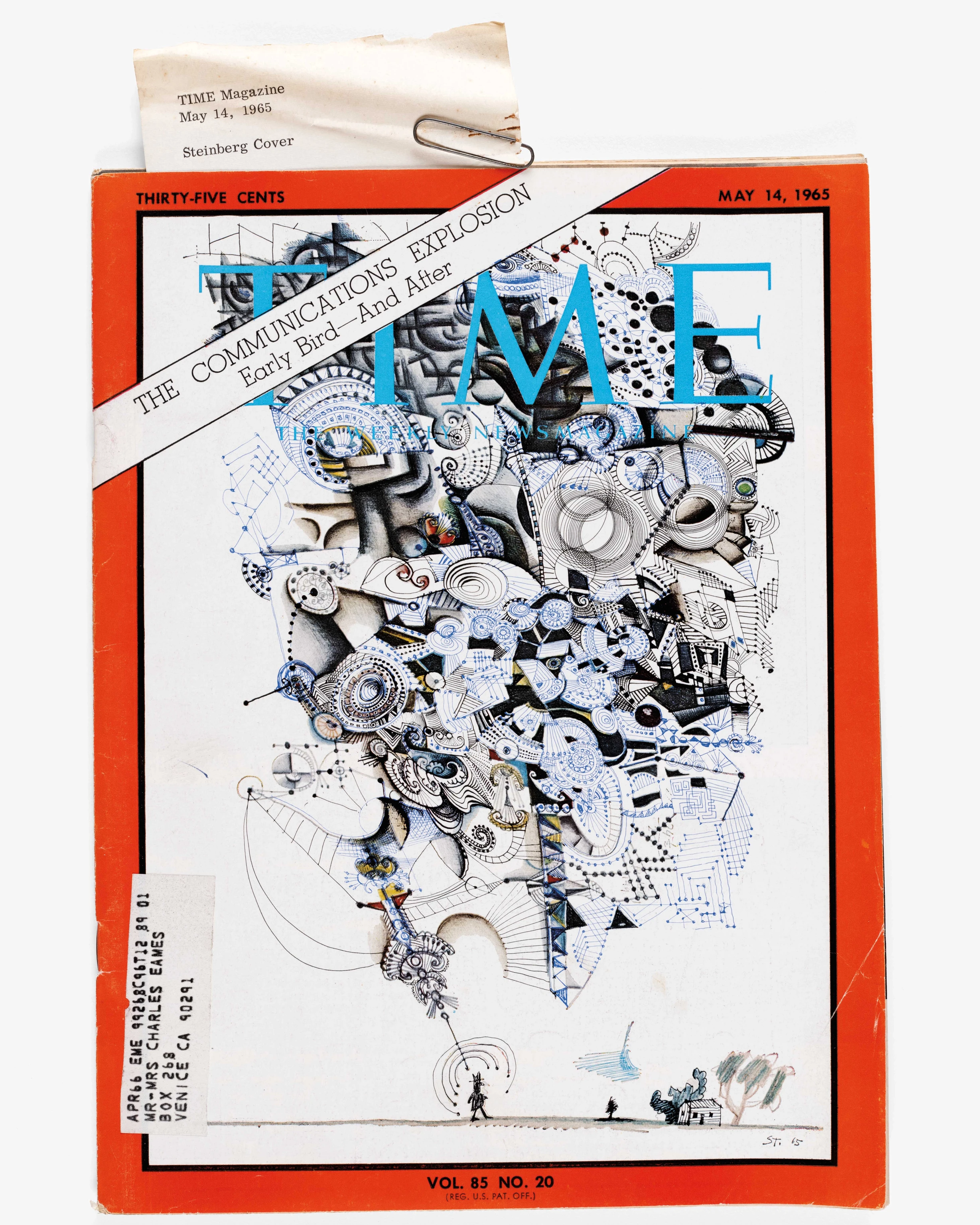

These collaborations—two of which remained within the Eames Office and resurface through the years in photo shoots and showroom designs—were of a piece conceptually and thematically with the work Steinberg had been creating earlier in the year for the short-lived publication Flair. Founded and edited by the visionary editor / socialite Fleur Cowles, the magazine was so rich in content and production features that it proved too costly to keep afloat and only ran for twelve issues over the course of 1950. Within the March and September issues, Steinberg conceived of two bound-in booklets, respectively titled “Portraits” and “The City.” In “Portraits,” one finds the precedent for the work at the Eames Office—drawings of people on unpredictable objects and surfaces. Photographers then captured the results on film, and only in the resulting image does one see the complete composite of drawing, object, and environment to complete the work. In the latter booklet, “The City,” objects are once again transformed through drawing, but in this case on top of the photograph itself.

The editorial freedom and production resources of Flair offered Steinberg a platform to explore the blurred lines that separate the reality and the unreality of drawing, and pushed him to diversify his approach by including elements of his own material reality. Substituting furniture and environments for blank paper expanded the possibilities for expression and comment. Similarly, drawing on photography allowed for playful shifts in perspective or seeing the mundane anew. His brief but productive encounter with the Eameses undoubtedly benefited from these creative explorations.

The Steinberg arm shells remained favorites within the office and were, on occasion, used in installations and photo shoots.

© Eames Office, LLC

Although Steinberg and Sterne departed Los Angeles in September of 1950, Eames chairs continued to appear in his drawings and the couples remained in contact. From time to time, the Eameses called on the artist to produce additional diplomas to give as commemorative gifts to mark special occasions. While some of their collaborations live on in only photographs, the two surviving chairs—of the nude and the cat—have been exhibited extensively through the years and are a testament to the timelessness of both Steinberg’s and the Eameses’ creative vision. As if that pair of chairs were not enough, even Charles was left wanting. In a letter to Steinberg dated January 8, 1951, he wrote: “Don’t completely forget about that movie of the drawing of the town. It has really been haunting me. (Should have done this last summer.) I think it would be terrific in drawing, in rhythm and contrast, and with the right music for it, could be a very complete package. This should not wait too long. It’s later than you think.”