Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen may have won MoMA’s 1940 Organic Design in Home Furnishings competition (in both “seating for a living room” and “other furniture for a living room” categories), but the failure of the designs to be realized as they were intended radically reshaped Eames’s entire approach to design.

While the ethos and aesthetics of the furniture were sound—with designs that utilized three-dimensionally-molded plyformed wood shells, thin upholstered pads, and patented connector joints, to create lightweight and low-cost solutions for comfortable seating based on human factors—the imaginations of the designers eclipsed the abilities of manufacturers. Eames soon realized that the real medium for industrial design was industry, not paper, and that the successful designer must work diligently to fully understand, embrace, and overcome constraints at every stage of production. Divorced and remarried to Cranbrook student Ray Kaiser in 1941, Eames set out for a new life in Los Angeles, California, and instigated a remarkable period of research and exploration that would see the couple evolve from moonlighting novices to masters of mass production—and set the stage for a lifelong journey in the pursuit of problem-solving design.

“Alakazam!”

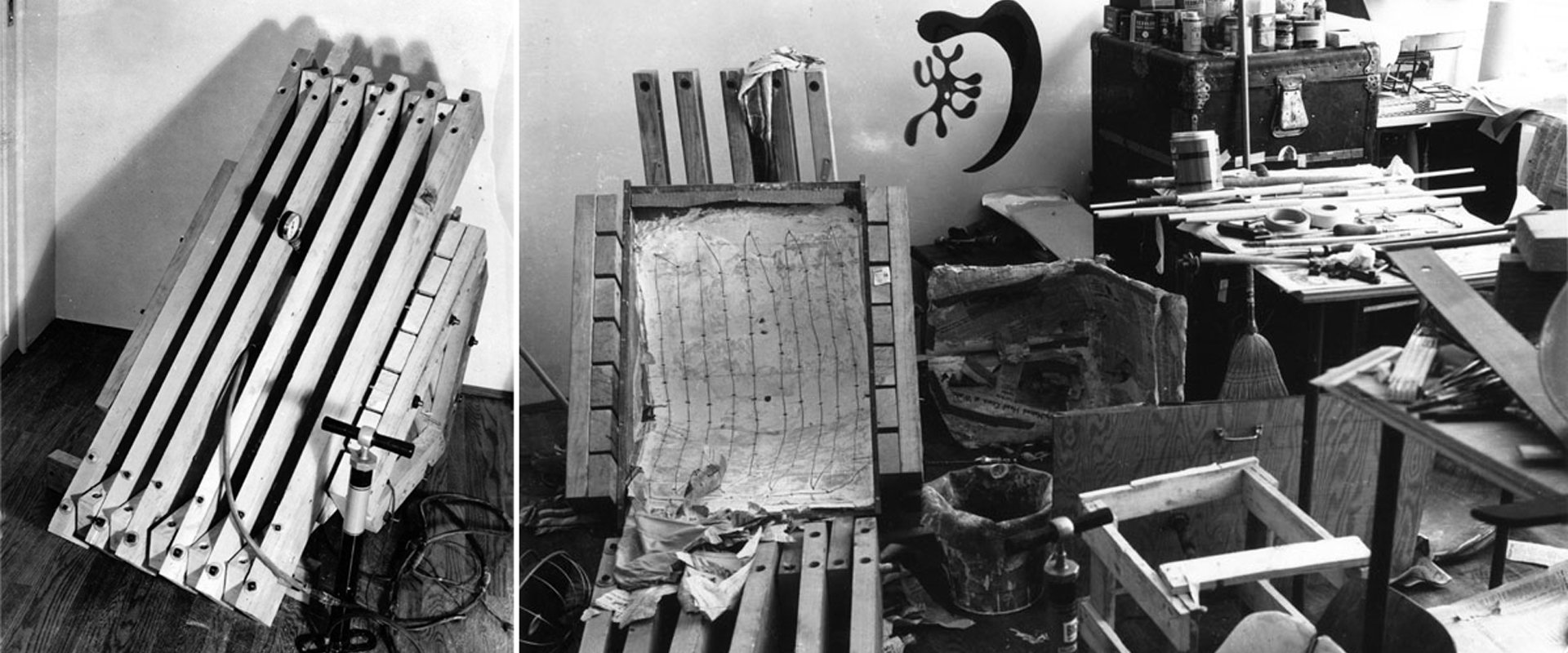

Left: Kazam! machine at Ray and Charles’s apartment, 1942. Right: Kazam! machine open at Ray and Charles’s apartment, 1942. Image © Eames Office, LLC

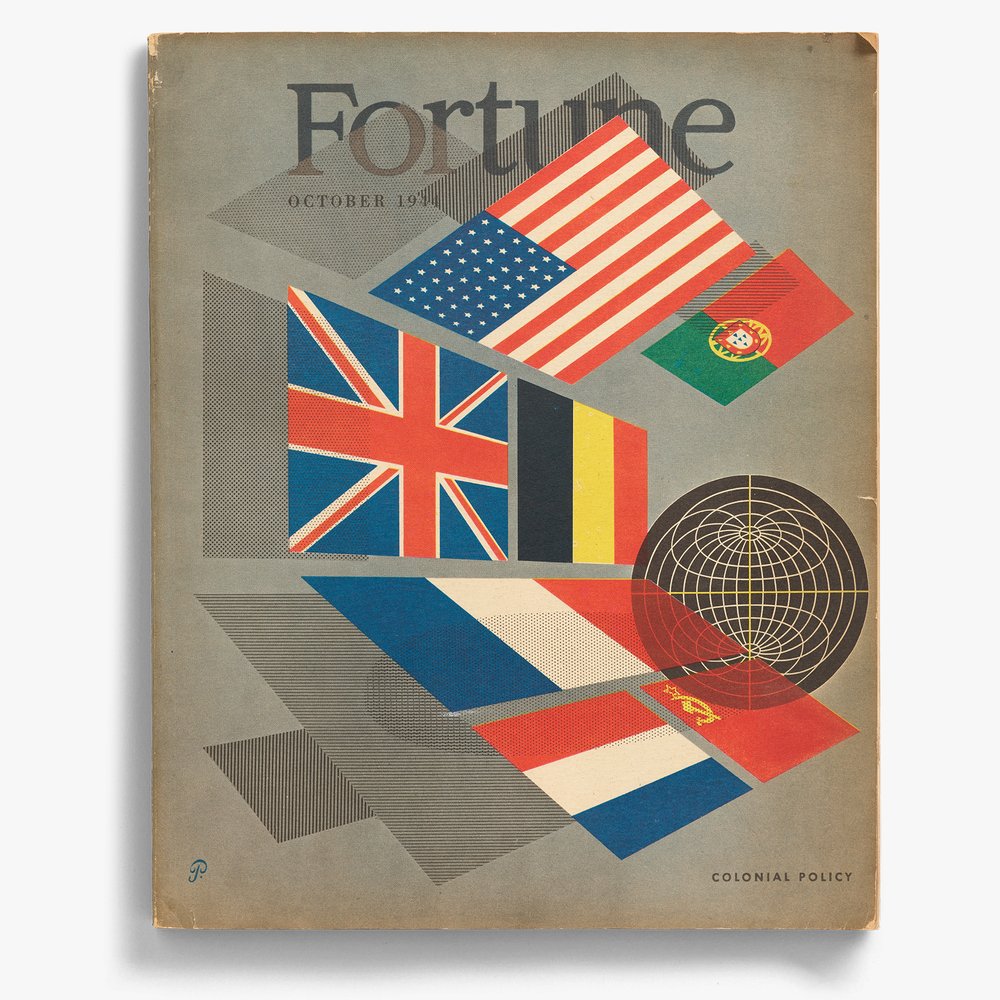

After Ray and Charles arrived in Los Angeles, they soon befriended John Entenza, editor and publisher of the influential Art & Architecture magazine—where they served on the editorial board and offered frequent contributions, including more than two dozen cover designs, and collaborations with influential friends and colleagues. Charles found work in the art department at MGM studios, making architectural renderings of set designs for directors including Vincente Minnelli and George Davis.

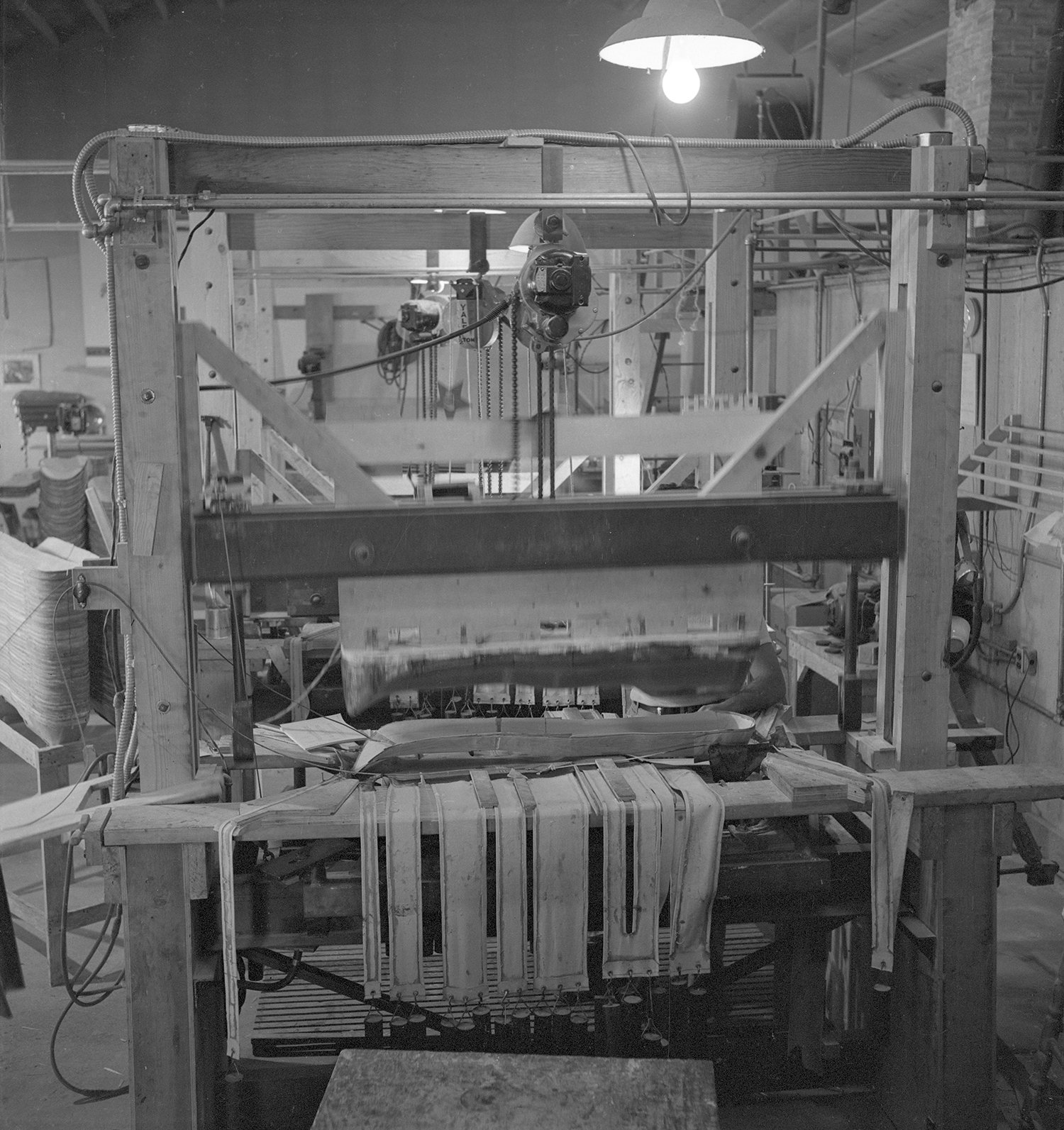

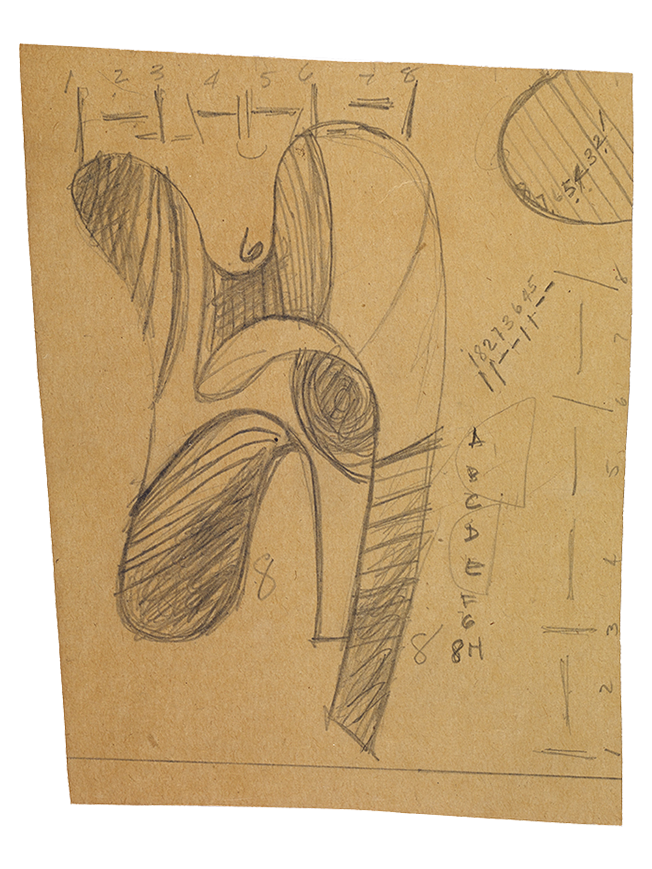

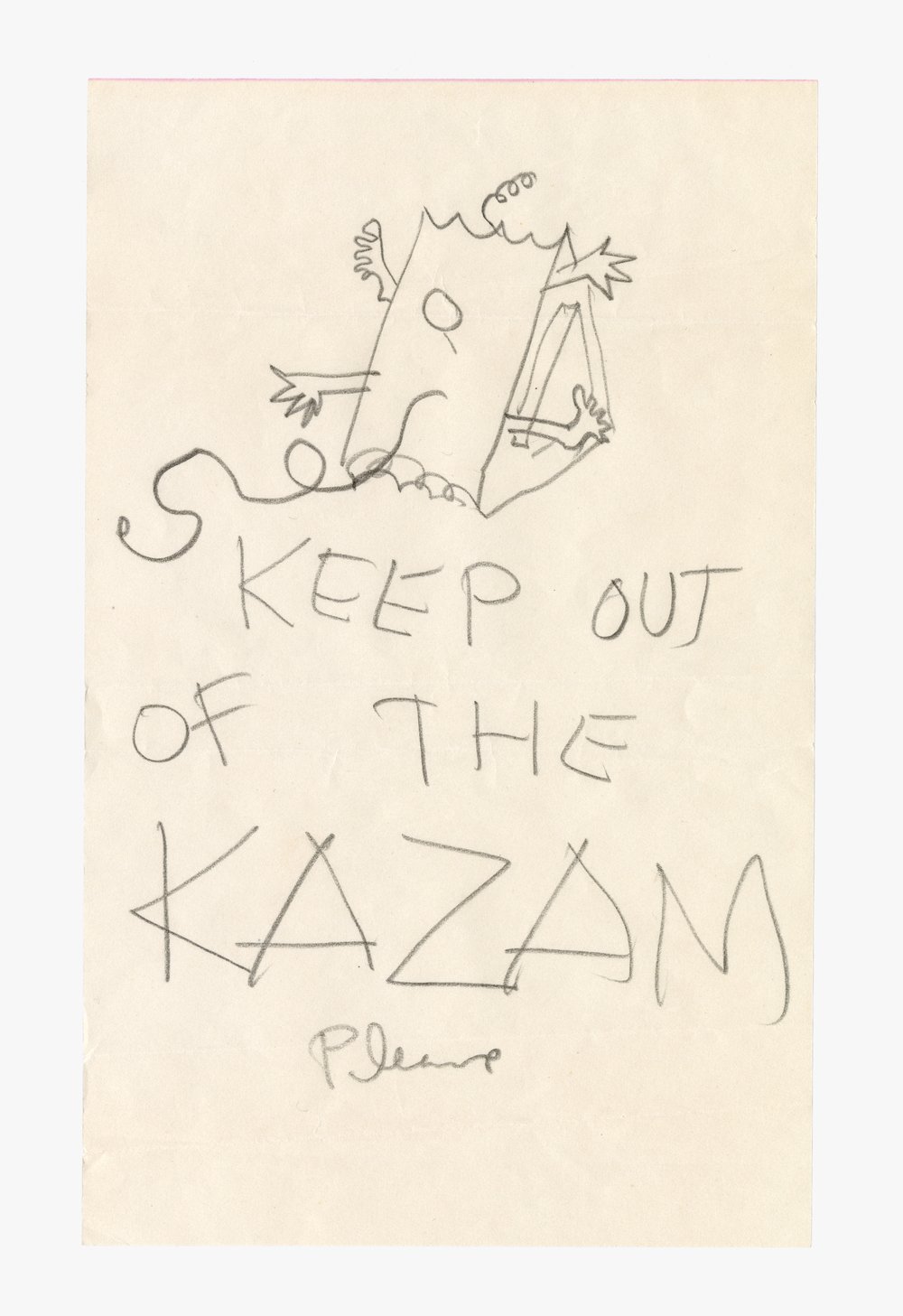

On weeknights and weekends, Ray and Charles pursued their consuming interest—high-performance, low-cost furniture—devising a machine that could fabricate the molded plywood shapes they had begun experimenting with for the MoMA organic furniture competition. In the second bedroom of their Richard Neutra–designed Strathmore apartment, Ray and Charles constructed a plywood-curing oven out of lumber, electric coils, plaster, and a bicycle pump. Ray named the device for a phrase from a magician’s act—the words uttered in the final moment when an alchemical change has been effected, “Ala Kazam!” The Eameses’ Kazam! machine was engineered to metamorphize—molding wood into an endless variety of shapes with applications that defied belief about what plywood could do. The undertaking was risky, not least because the oven required more current than the Eameses could source from their apartment’s internal wiring. Charles hiked up a utility pole to siphon the energy they needed from the street—a harrowing errand that had electrifying consequences for the world of design.

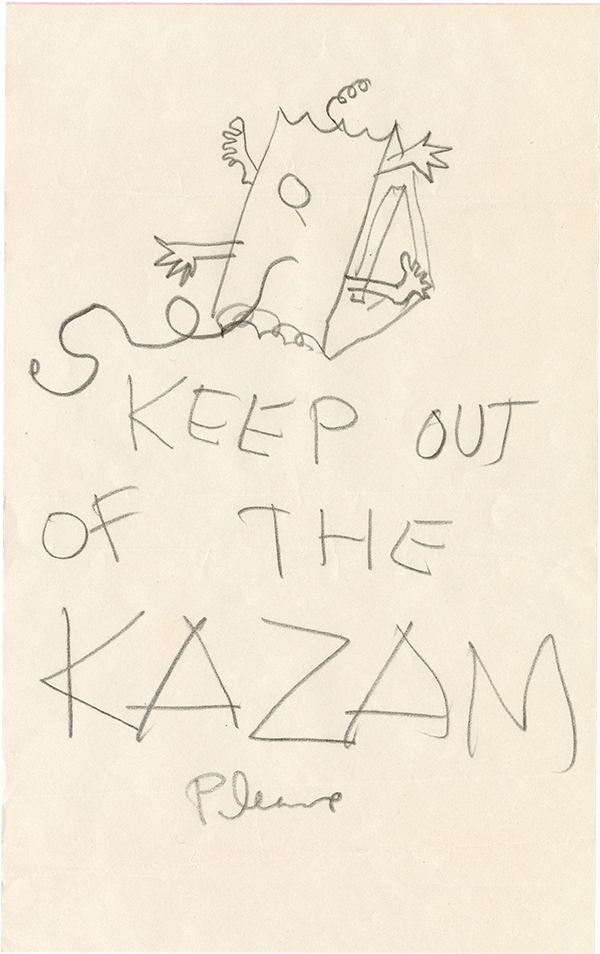

“Keep Out of the Kazam Please” note with drawing by Charles Eames, 1942

Photograph of plywood seat shell made in Kazam! machine, 1942. Image © Eames Office, LLC

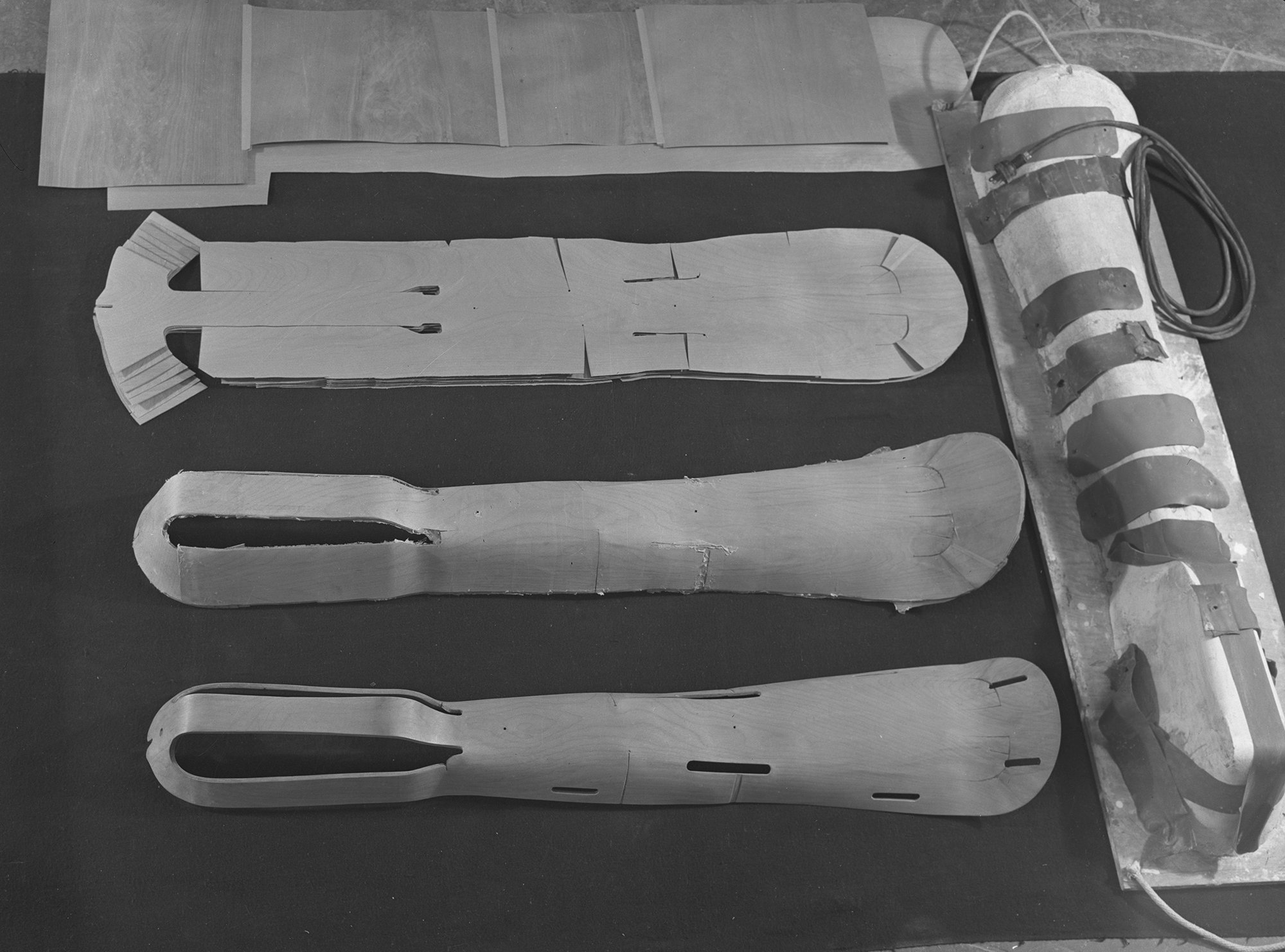

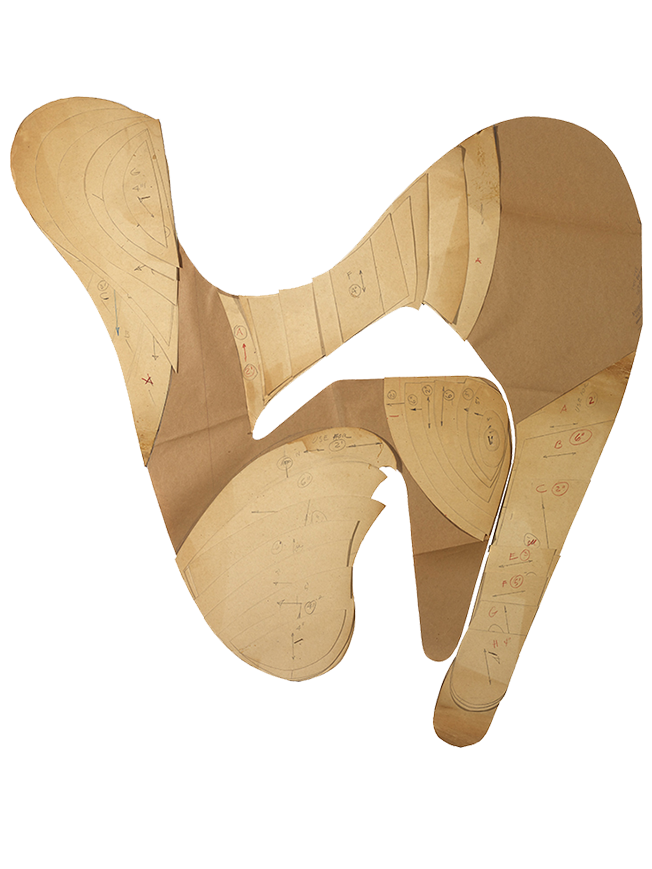

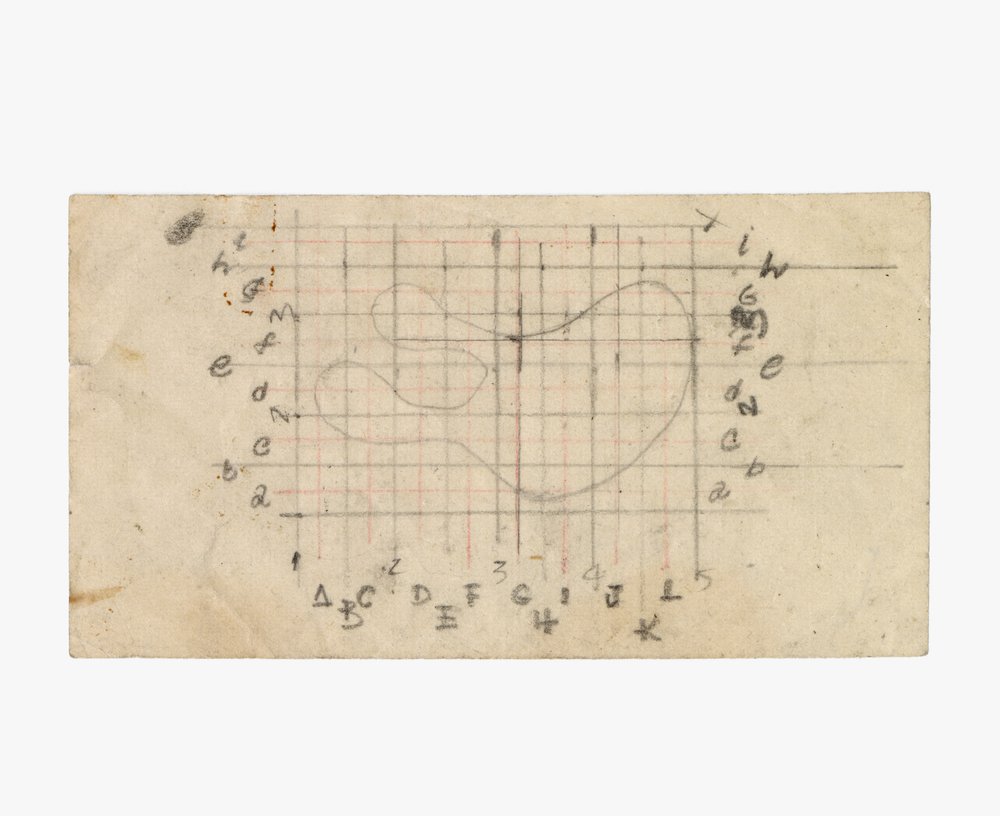

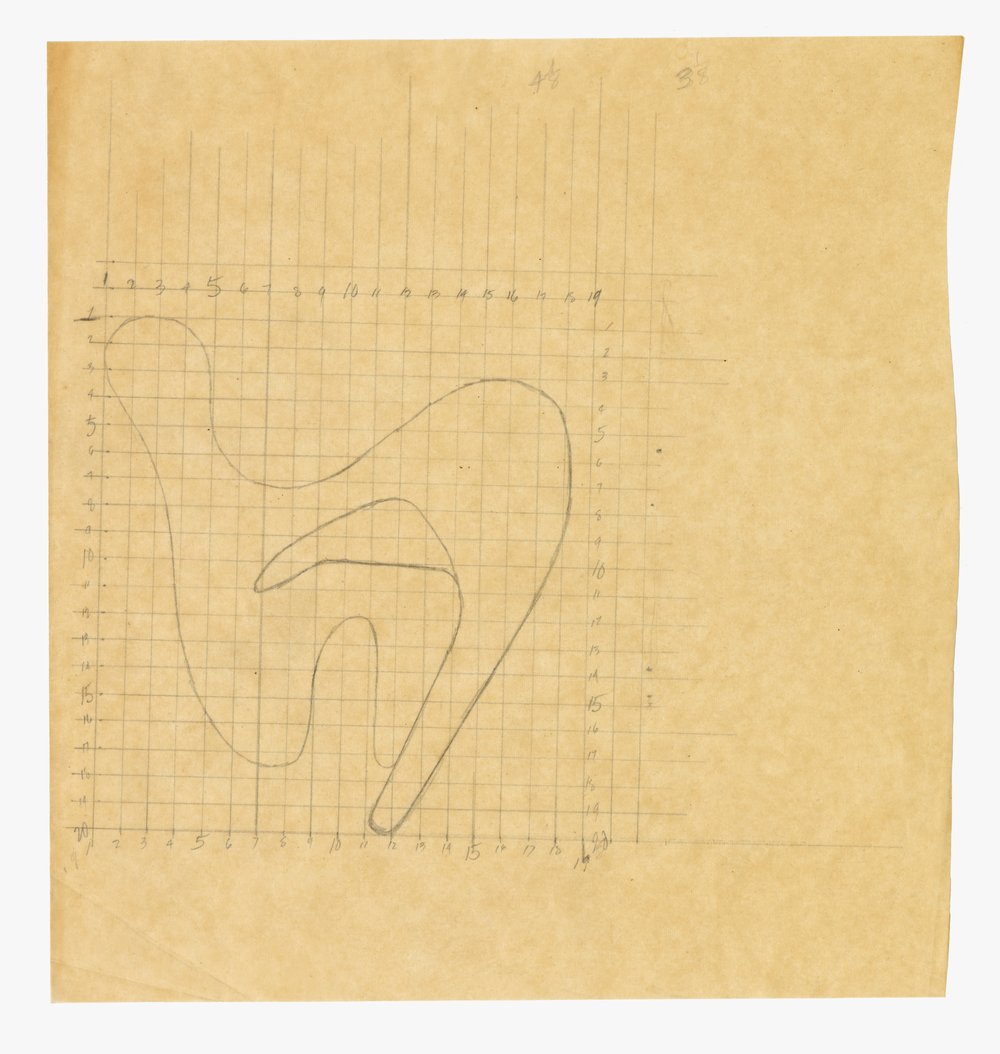

The Eameses began with a prototype for a single molded shell chair, a design objective that originated in the organic design competition and in effect became a lifelong pursuit. The rationale behind a single-shelled chair being that it could be produced with less materials, in fewer steps, with less connections, and those savings could be passed along to the consumer. Their earliest prototypes were painstaking efforts: dozens of hand-applied, glue-painted layers (or plies) of wood pressed into the Kazam!’s chair mold by an inflatable membrane while a heating mechanism firmed the glue for four to six hours. Afterward, Ray and Charles smoothed the wooden shell with a saw or sander in a hands-on, trial and error process. Despite the sturdiness of laminated plywood, the combination of curvature and pressure would cause the shells to split at their weakest points. Ray and Charles experimented with various slices and keyhole openings in the plies to promote torsion and give—an evolving technique that resulted in hundreds of unnamed iterations.

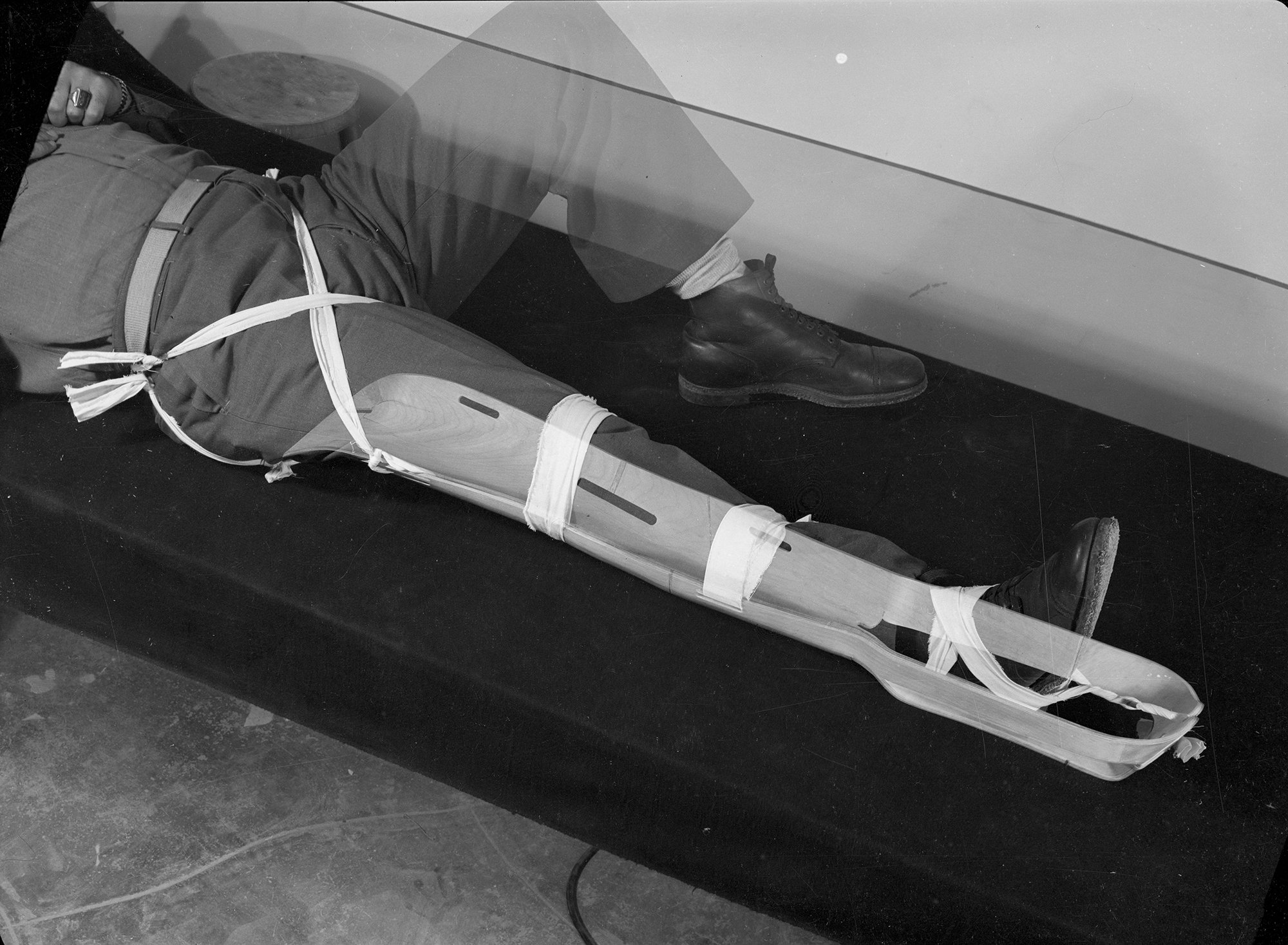

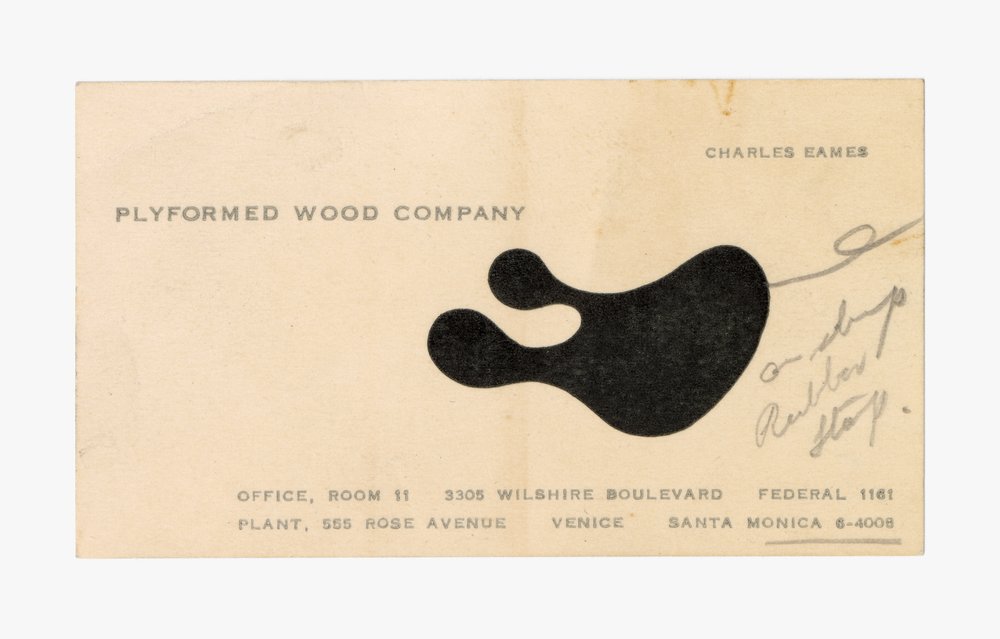

For Ray and Charles, their engagement with design was grounded in utility as they sought to fabricate objects to solve specific problems. When, in late 1941, Dr. Wendell Scott, a St. Louis, Missouri, acquaintance, told them about the inadequacy of the metal splint used by the US military, they chanced upon a problem that spoke to their fundamental concerns. Here was a sorely needed tool with specific objectives from medical and combat professionals: the splint had to be lightweight and stackable for transport, support the natural curve of the human leg, and tightly secure the limb without cutting off circulation. Ray and Charles immediately set about adapting their plywood molding process to the problem at hand, and together with John Entenza, architect Gregory Ain, and Margaret Harris and Griswold Raetze from MGM, formed the Plyformed Wood Company to formalize their operation.

The Eameses began by shaping a plaster mold of Charles’s leg to create a positive form to shape a mold. The couple’s experimentation followed along similar lines as for seating, letting the ultimate form of the splint be guided by the shape of the body and the constraints of the plywood production process. (It was rumored that Charles even sought input on what kind of holes and darts to make in the veneer plies from seamstresses in MGM’s wardrobe department.) The gaps in the veneer that were necessary to allow the plywood to bend into shape also offered ideal slots for threading bandages and securing the limb.

The newly formed company also began looking into other applications for their techniques and technology—including a body litter intended for transporting wounded soldiers out of harm’s way. The team utilized a similar human-centered design process for that by which the Eameses formed their first plywood chairs, using a flexible “blanket” of wooden dowels to help determine the critical areas of support required of the device. An early prototype features a more hourglass-like curvilinear form, while a second more refined design was developed to accommodate a wider range of body sizes. Neither went into production as the arrangements to produce the splint in quantity demanded the team’s full attention.

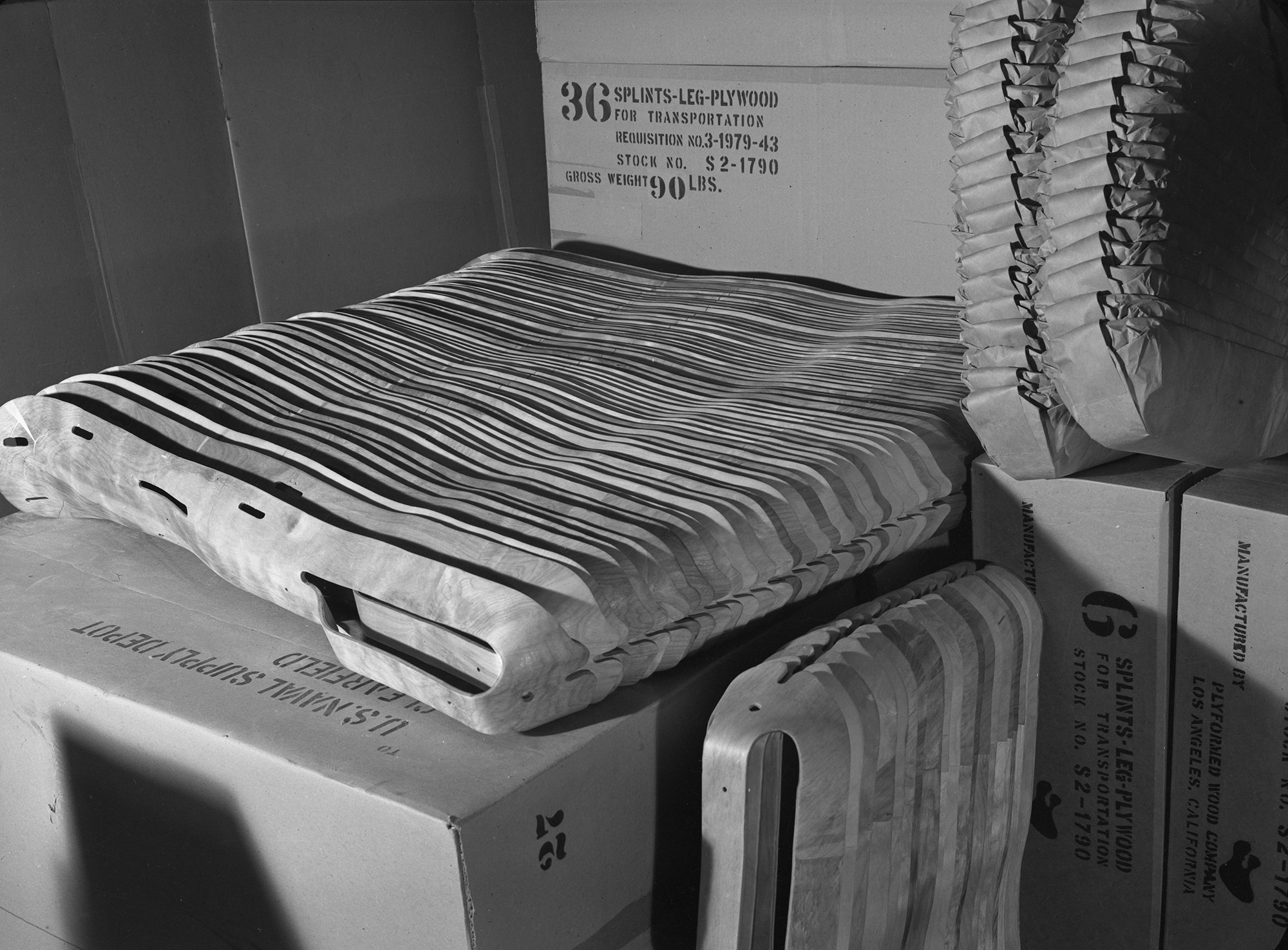

In November of 1942, the Navy placed an order for 5,000 splints, but the the nascent Plyformed Wood Company lacked the capital to invest in the necessary tooling, secure an inventory of materials, or even pay employees—who by 1943 included the Eameses’ former Cranbrook associate Harry Bertoia and Swiss-born photographer and designer Herbert Matter. To remedy the situation, Charles reached out to Colonel Edward S. Evans, head of the Evans Product Company. The Detroit, Michigan–based company owned vast tracts of Douglas fir and cedar in the Pacific Northwest and were intrigued by the possibility of expanding the market for products that would utilize their timber. Ultimately, a mutually agreeable arrangement saw the Plyformed Wood Company transformed into the Evans Molded Plywood Products Division (of which Charles was appointed director of research and development).

Evans Products Company splint label, 1943

By war’s end, the reinforced and expanded company had produced some 150,000 splints. Funds from their military contracts allowed the Eameses and architect and chief engineer Gregory Ain to devise faster, larger, and more efficient versions of the Kazam! machine, introducing a sheet metal mold, and enabling more complex forms, such as plywood trusses, coils, springs, and joints. Plywood was already integral to the fabrication of British aircraft, and the Molded Plywood Products Division began to develop experimental aircraft parts and gliders at a time when the military didn't have an adequate supply of metal—from pilot chairs to hulking nose cones or “blisters.”

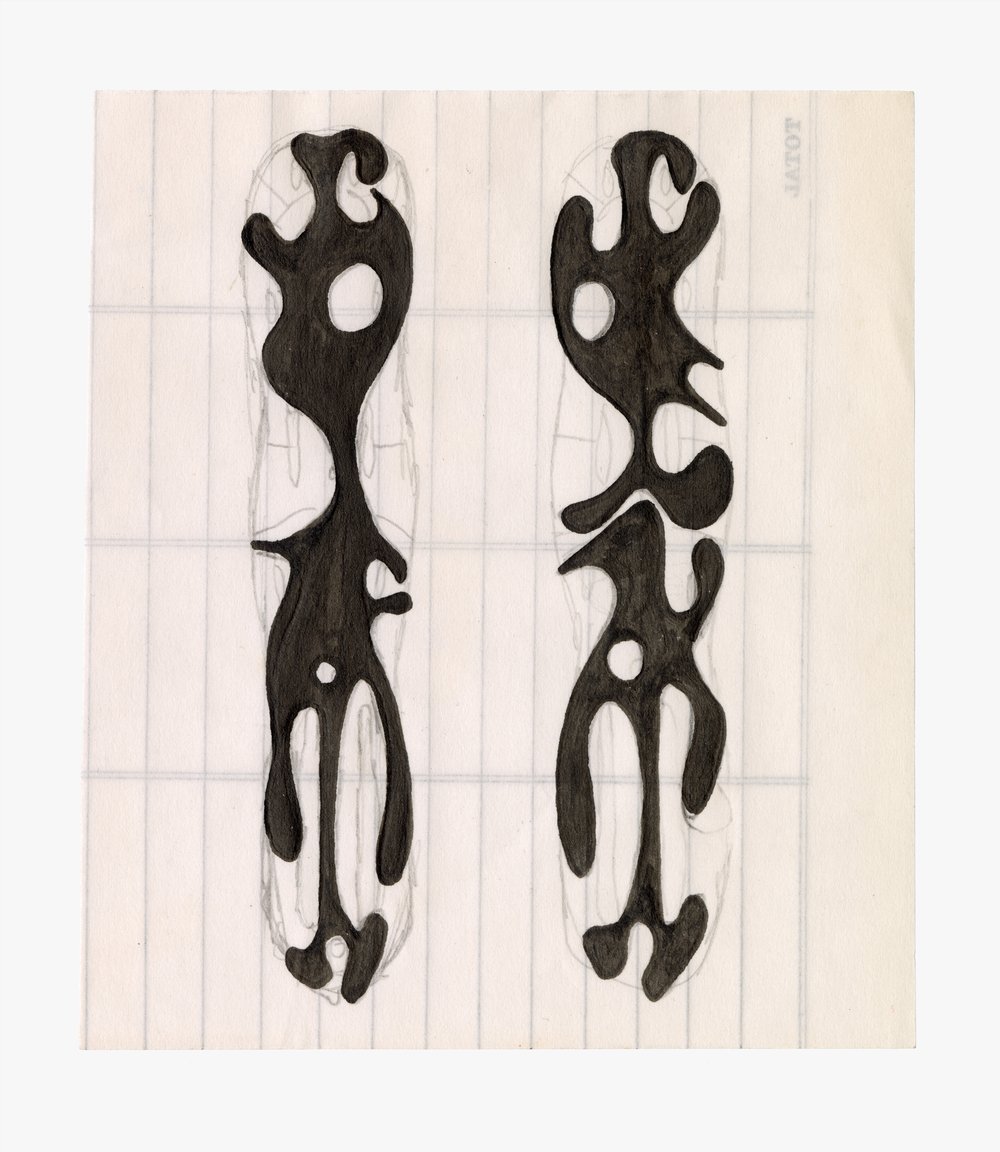

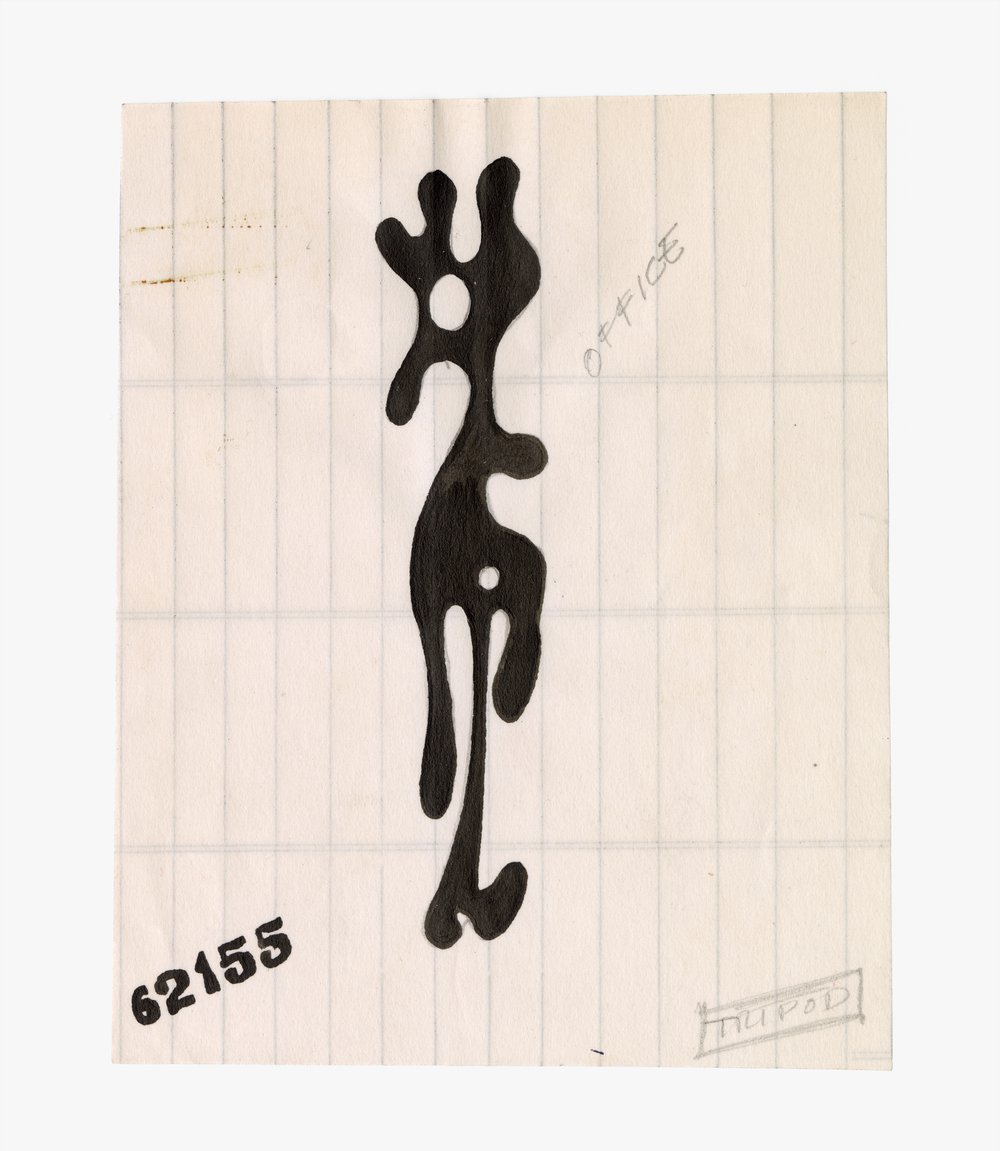

Many of these designs were ultimately unrealized commercially, but the deep involvement in the development process—a perpetual cycle of ambition, experimentation, and refinement—catapulted the Eameses and their cohort to an unrivaled level of technical mastery. During this time, Ray and Charles further solidified an ethos that would guide their work for decades to come: removing, to the greatest extent possible, any marks of artistic self-expression in an effort to eliminate idiosyncrasies that get magnified in mass production, and distract from the purpose of the design. There is, in hindsight, some irony to this: the pair created what any impartial observer would deem sculptures in an effort to better understand and push the limits of their molding capability (as well as three known examples of sculptures carved from splints themselves). Nonetheless, through the lens of time and removed from its original purpose, a factory-produced splint is in and of itself a work of art. This beauty in utility was undoubtedly not lost on Ray and Charles—a remarkable series of photographs by Herbert Matter portrays airplane fuselage sections as monumental sculptures better suited to the halls of MoMA than a military hangar.

Photograph of production of molded plywood airplane parts, 1943. Image © Eames Office, LLC

Photograph of production of molded and laminated plywood airplane parts, 1943. Image © Eames Office, LLC

Stages in Development for the Production of an Object

In 1942 to 1943, Ray and Charles developed plywood sculptures to explore potential production of new designs in the material. Years later Ray recalled “There were a couple of sculptures. They were not just done as sculptures, as such. It was really a way of testing ... So much was learned from those. There were two major pieces. They were attempts to discover as much as we could about the nature of the wood and plywood.”

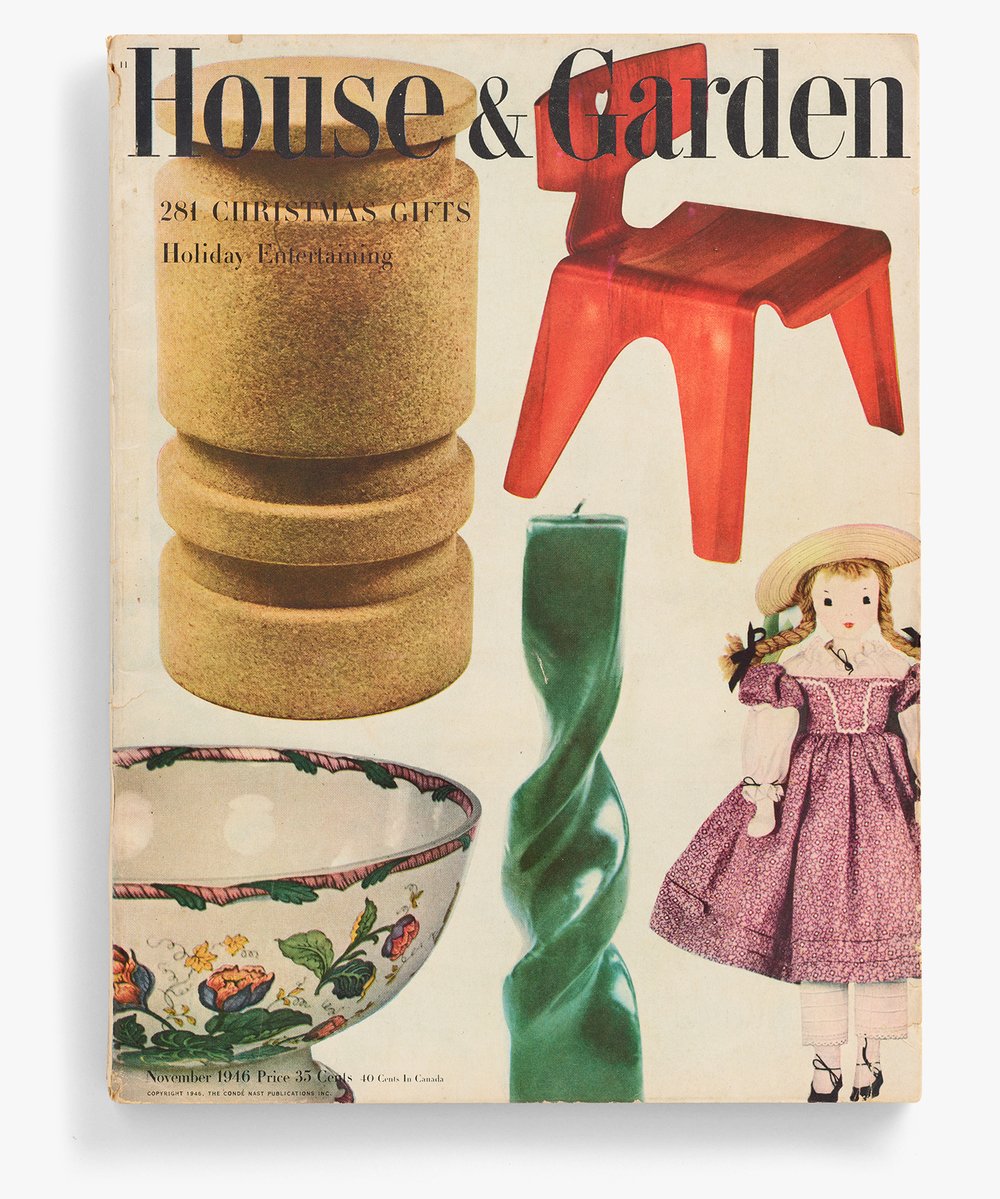

In 1945, as the war was winding down, the Eameses again returned their attention to furniture. Starting small, they produced a line of children’s furniture made of laminated birch in natural and bright aniline-dyed colors—including a low, two-piece chair featuring a heart carved into the back to double as a fingerhold. They sculpted fanciful molded toys, including an elephant for children to bestride and an abstracted horse, along with plans for a bear, a seal, and a frog that were only ever realized as metal maquettes. Most importantly, they also returned—with enhanced understanding, as well as the financial support of Evans—to their seating designs, turning out countless experiments on a path that would soon land them back at the Museum of Modern Art.

While the war years served up no shortage of challenges for Ray and Charles, it was also an incredibly productive incubatory period that saw them pursuing their passions and honing their craft. Through their contracts with Evans and the US Navy they were able to support the war effort (in a conscientious manner focused on helping people) while also experiencing, for the first time, the scaling of a design from prototype to mass production. Through their mastery of plywood and deeply nuanced understanding of the industrial processes necessary to its production, they demonstrated a new role for the designer in postwar society—as an agent of change at the vanguard of culture and commerce with the potential to uncover a heretofore unseen future. ❤

Photograph of stacks of children's chairs and stools, 1945. Image © Eames Office, LLC

Explore all artifacts

Dive into the exhibition—item by item. Clicking on an entry takes you to an artifact detail page containing pertinent details, more images, and in the case of some objects, curatorial notes.