Before Charles Ormond Eames Jr. and Bernice “Ray” Kaiser met and joined together as creative and romantic partners, their lives developed along strikingly parallel paths. Marked by grief from the loss of close family members, both Ray and Charles harnessed curiosity and creativity as survival skills, tools that allowed them to help themselves and then to help others. Each applied a prodigiously inventive intelligence and diverse array of talents to an astonishing number of expressive forms and industries. A shared ethic would form the backbone of their work together: an awareness that utility and sound structure were the basis of any object’s enduring value. Throughout their education and early careers, Ray and Charles embraced modernist mentors and ideals and developed the skills that made them profoundly complementary designers who, no matter what medium they tackled, always recognized that their work revolved around the human experience.

Early Charles

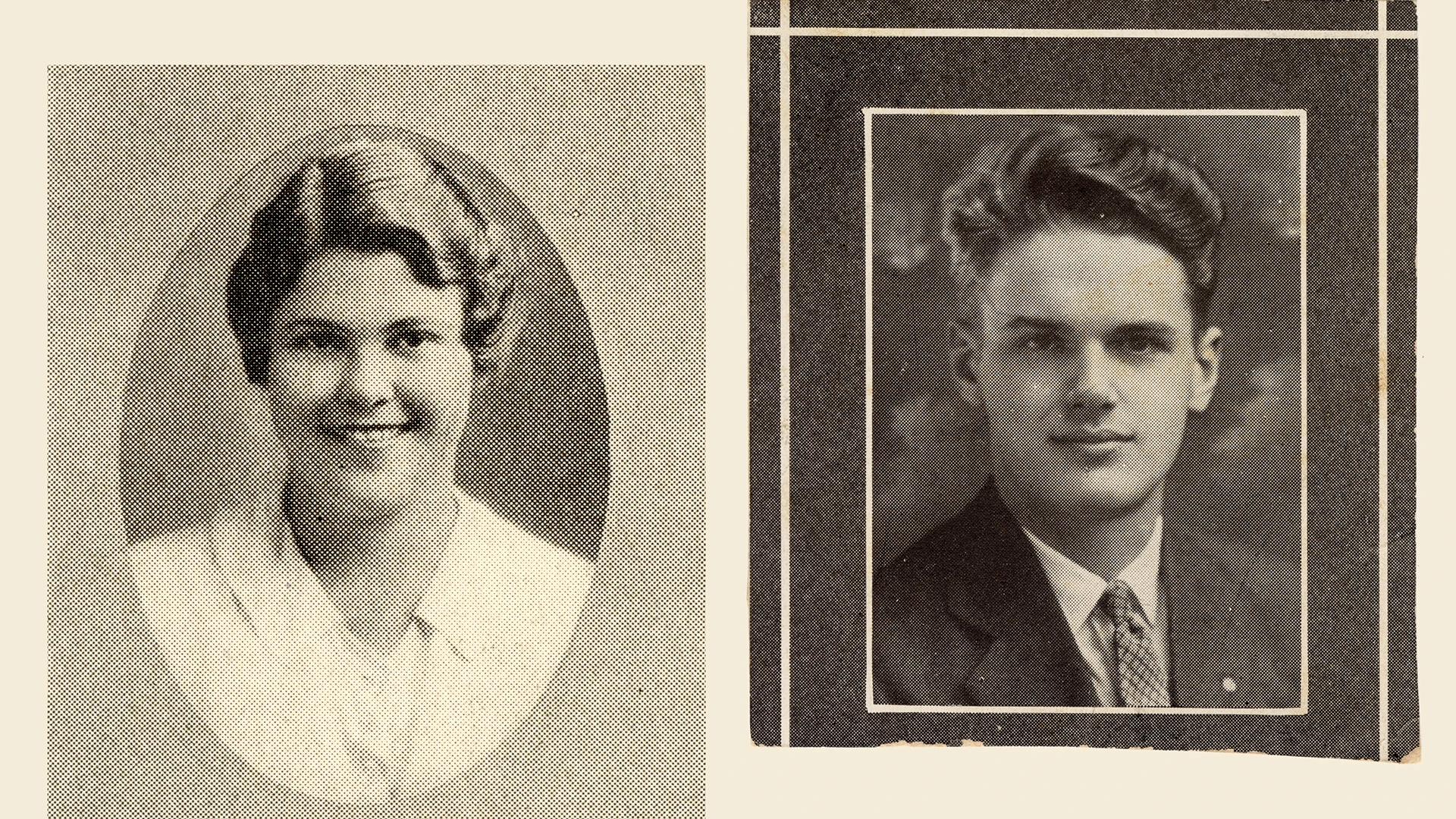

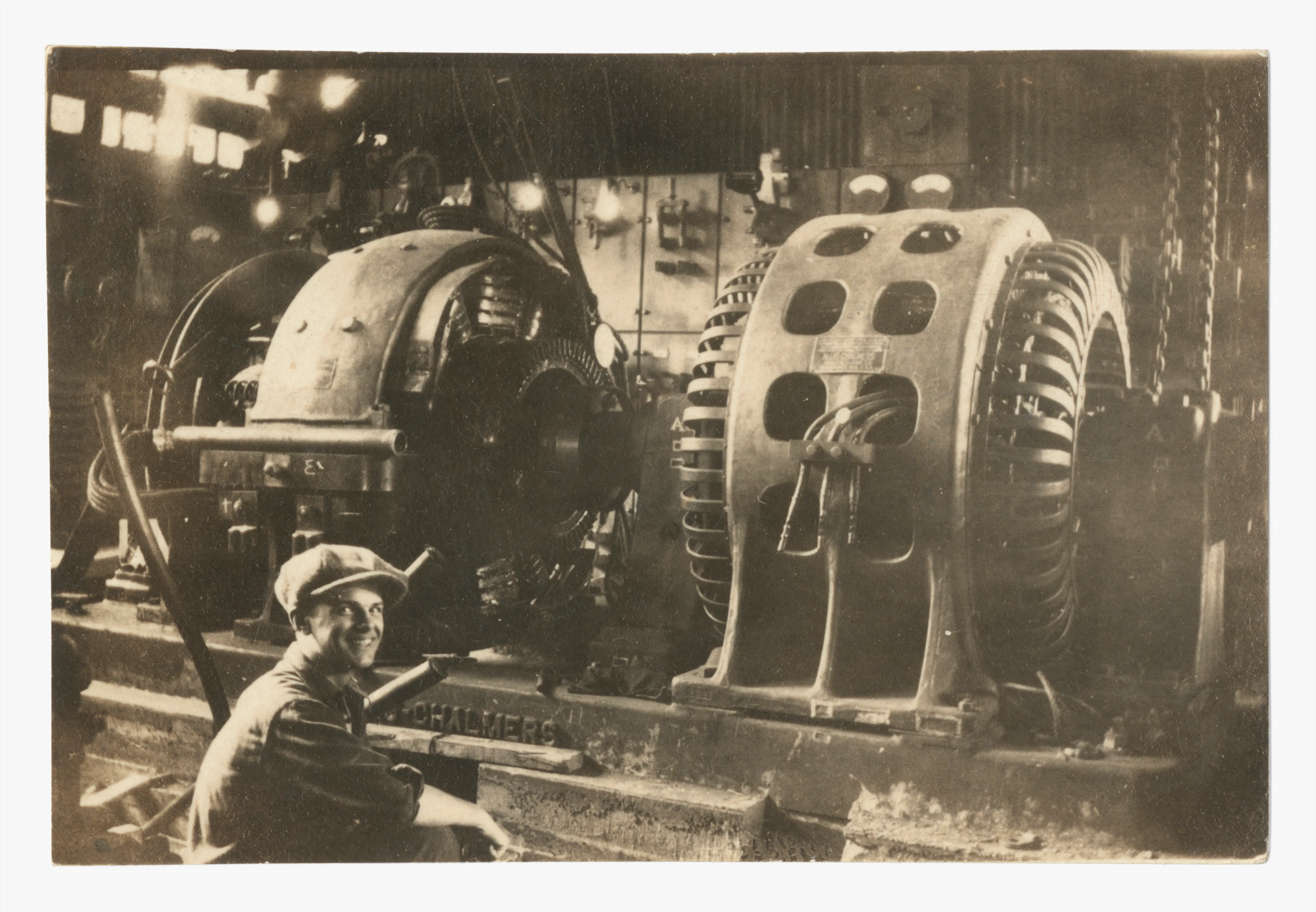

Charles Ormond Eames, Jr. was born in St. Louis in 1907 to Marie Celine Adele Pauline Lambert and Charles Ormond Eames, a Civil War veteran who worked as a Pinkerton detective and who practiced amateur painting and photography. After his father’s death (he was shot by train robbers while on assignment and never fully recovered), the family struggled to get by on a widow’s pension. To help make ends meet, Charles found his first job at age ten at a printing press, then at a pharmacy, and later as a steel laborer at Laclede Steel Company.

Charles taught himself to use his father’s wet-plate emulsion photography equipment—a format well-suited to capturing landscapes and architecture—initiating a lifelong practice of producing still and moving images, in addition to drawing, etching, and painting. Charles’s drafting skills helped him advance at the mill to patterns and engineering work on the weekends. During the week, Charles was his high school’s class president, quarterback of the football team, and a contributing cartoonist to the school paper and yearbook. A rival factory offered Charles a scholarship to Washington University in hopes that he would graduate and return to modernize their operation. But Charles had already extended his interests beyond engineering; he was attracted to architecture.

At Washington University, Charles studied with architects Gabriel Ferrand, Lawrence Hill, and Paul Valenti who taught principles of Beaux-Arts design—the dominant French style of the nineteenth century based on the classical traditions of Roman and Renaissance building. Charles, however, recognized the importance of modern architecture with its ambitions for societal reform, honesty, and simplicity, and was particularly taken with the writings of Frank Lloyd Wright. Charles’s interest in Frank Lloyd Wright ran counter to the priorities of his instructors, and he was dismissed from the university without a degree. (In 1950, his friend Saul Steinberg offered four satirical diplomas for Charles as impish consolation.)

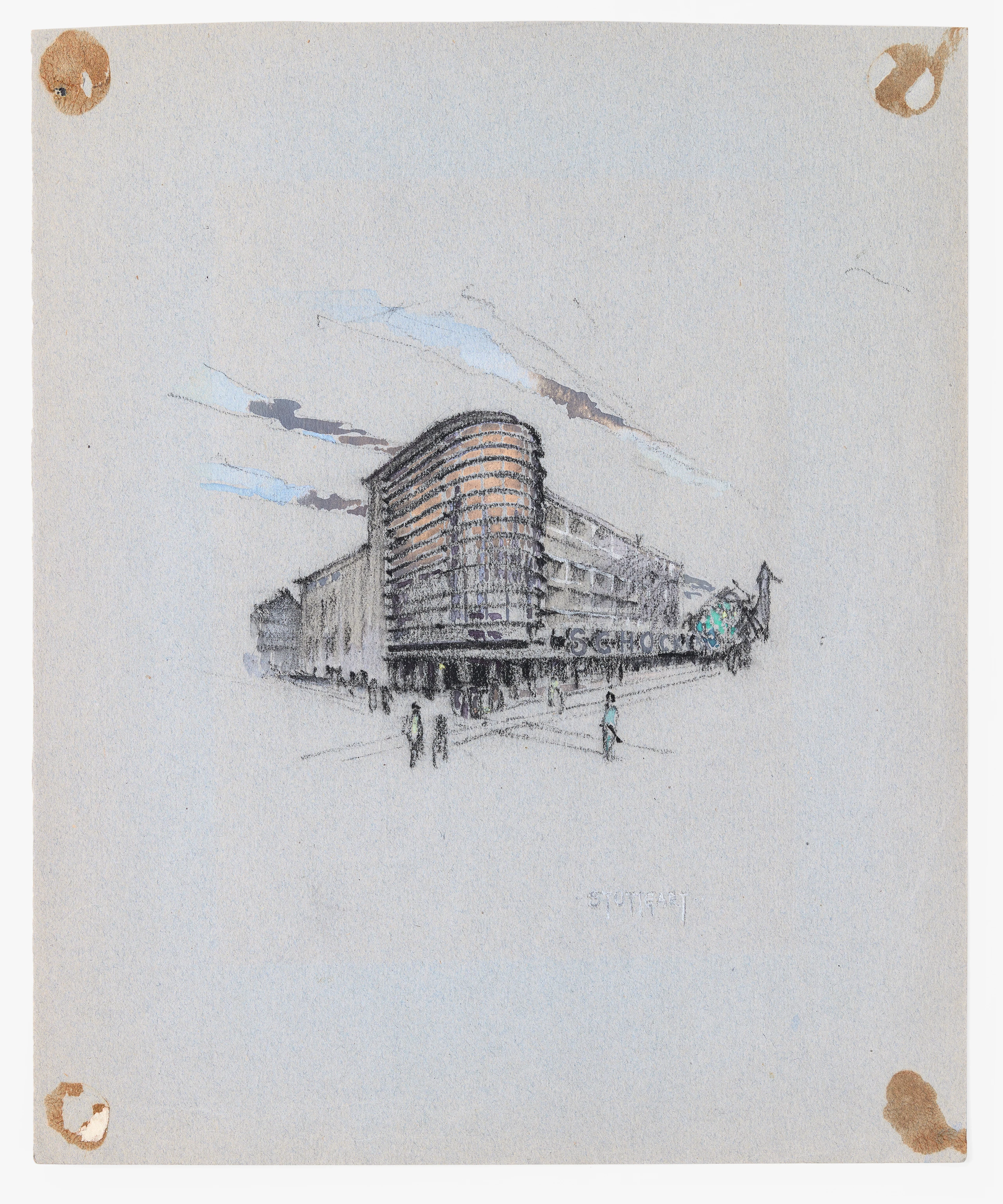

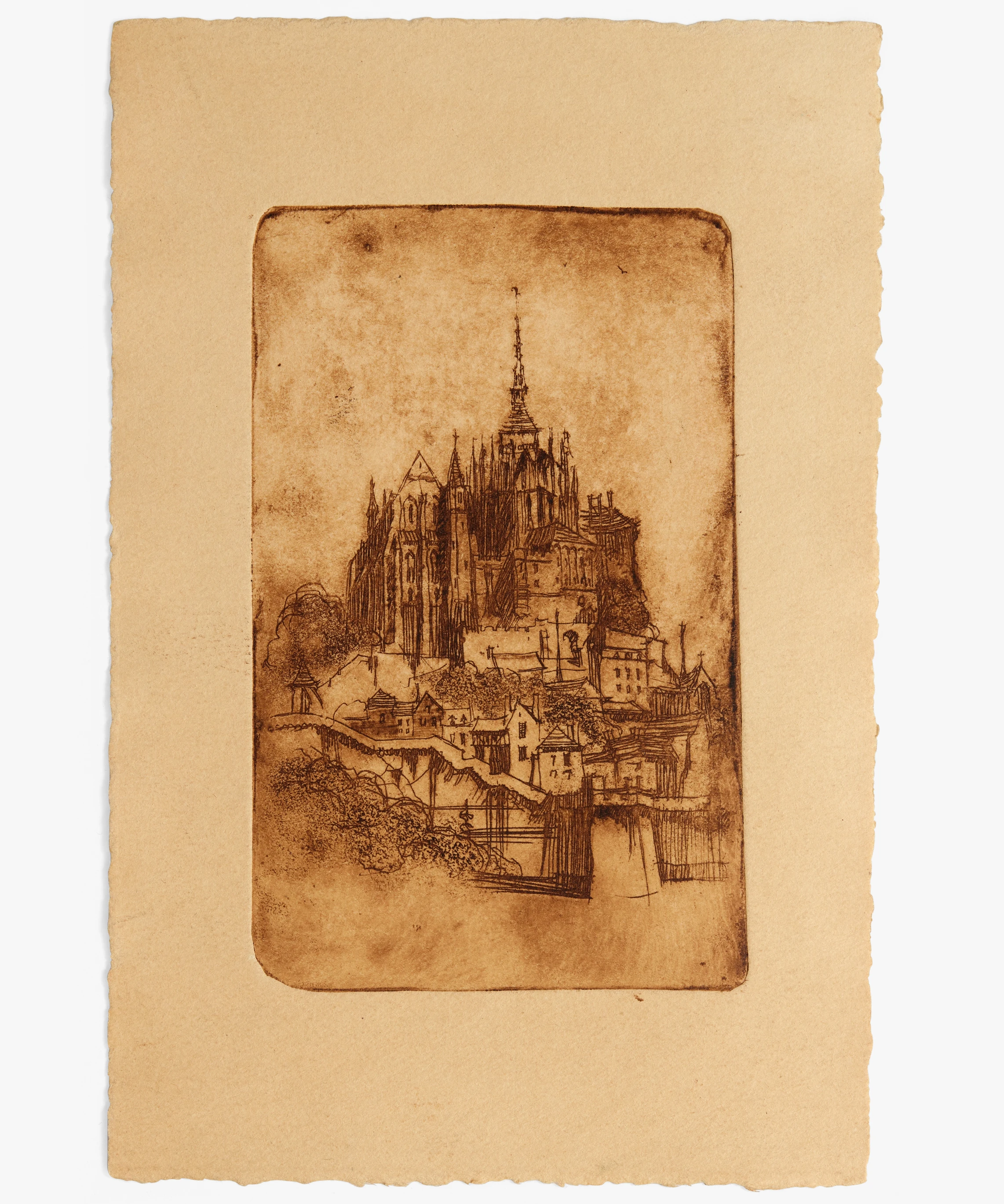

Charles was undeterred. As an undergraduate, he had already launched himself as an architect, working at the firm Trueblood & Graf. In 1929, he married fellow architect Catherine Dewey Woermann. On their honeymoon tour of Britain, France, and Germany, Charles sketched notable buildings, which Charles later turned into etchings. Here too Charles first encountered the work of International Style architects Mies van der Rohe, Walter Gropius, and Le Corbusier.

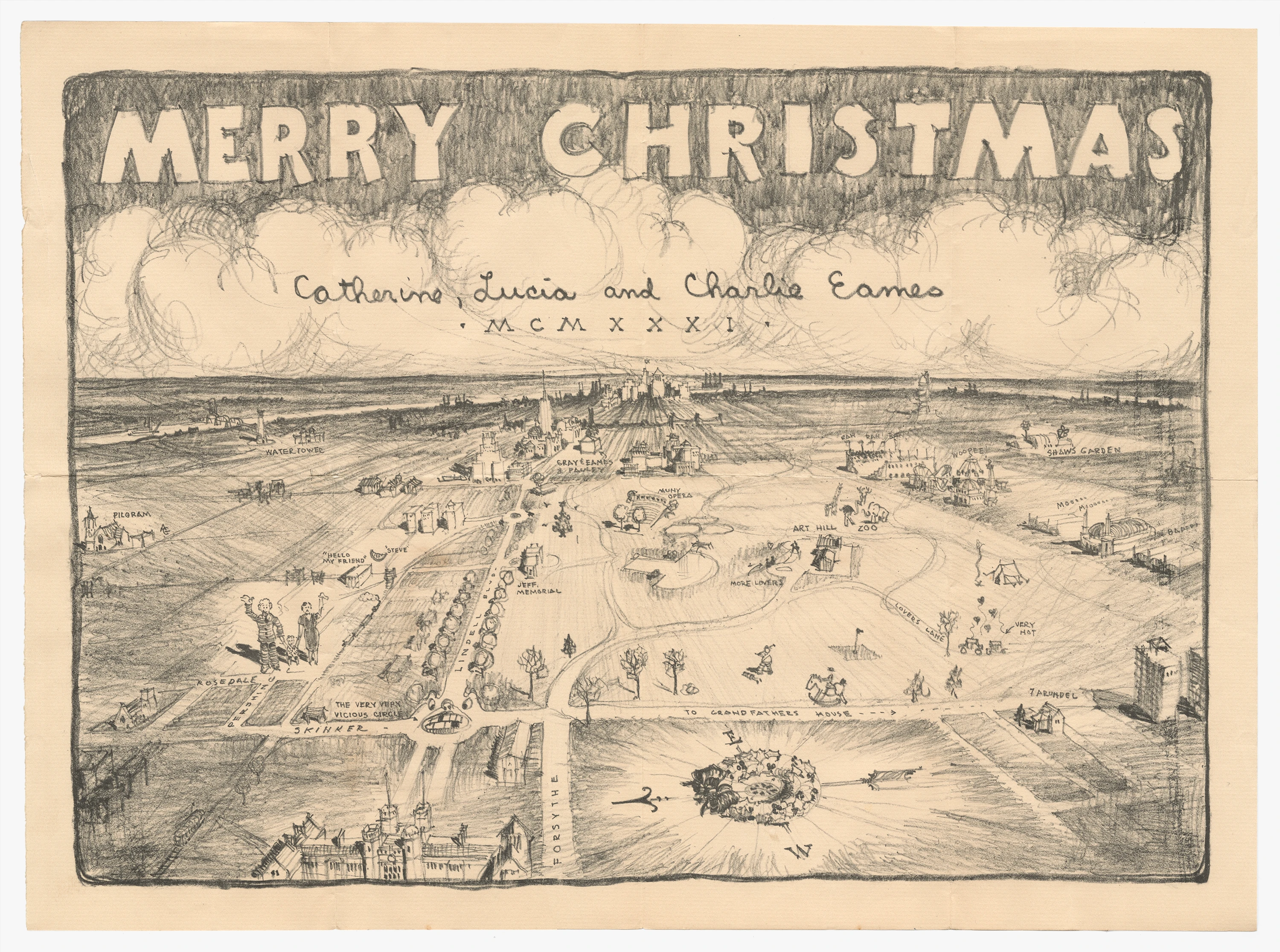

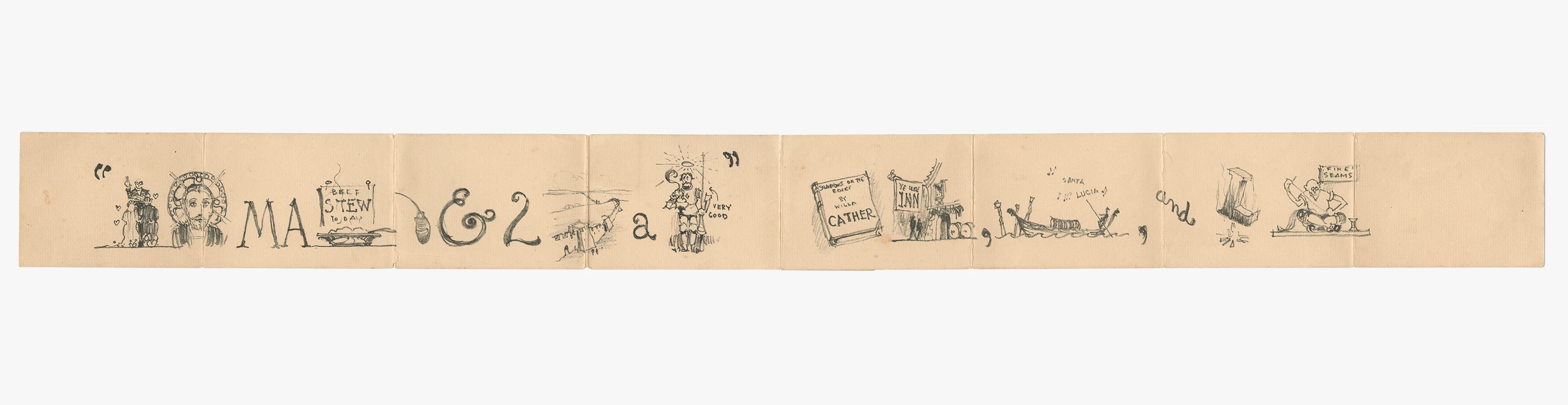

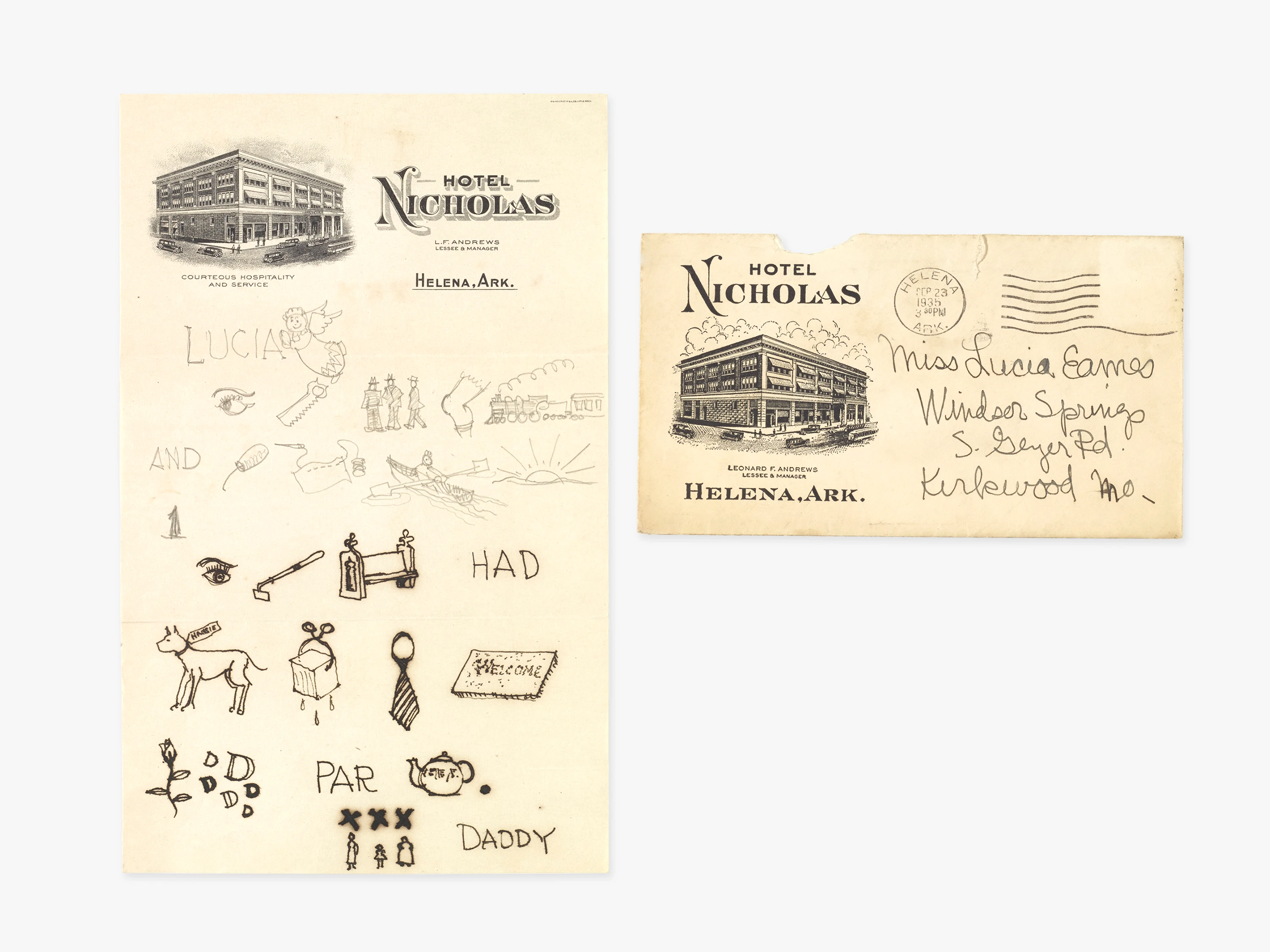

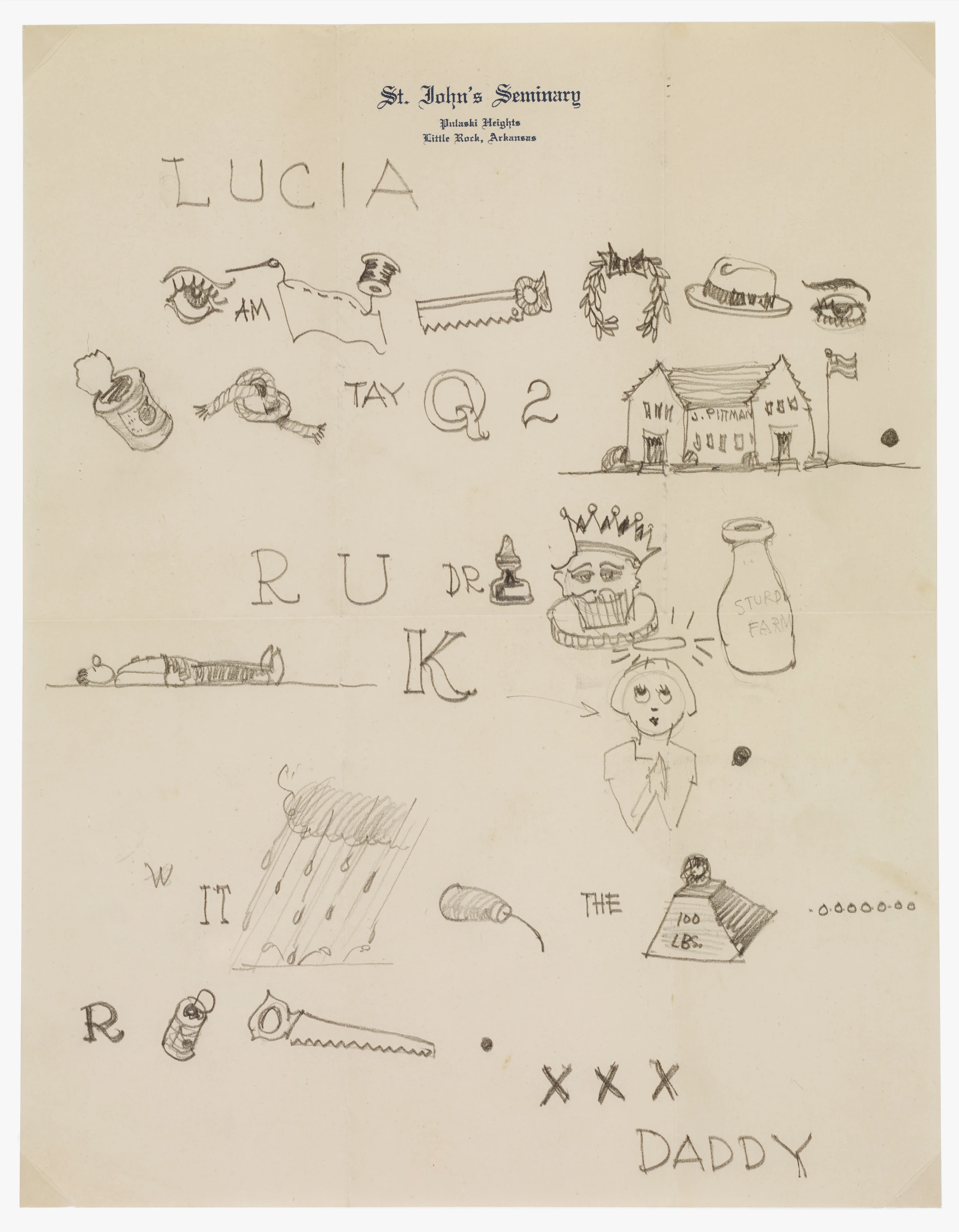

The economic collapse of the Great Depression had a crippling effect on Charles’s business prospects and upon the social fabric of St. Louis society, which was rife with desperation and alcoholism. Wife Catherine and daughter Lucia moved in with Catherine’s parents, while Charles attempted to pay their debts and departed for Mexico with only seventy-five cents to his name. He scraped by doing carpentry and the odd restoration of a church altar. Whenever Charles traveled, a steady stream of correspondence followed. His letters home include rebuses to Lucia that she delighted in deciphering—a mixture of image and wordplay, reflecting Charles’s consummate wit.

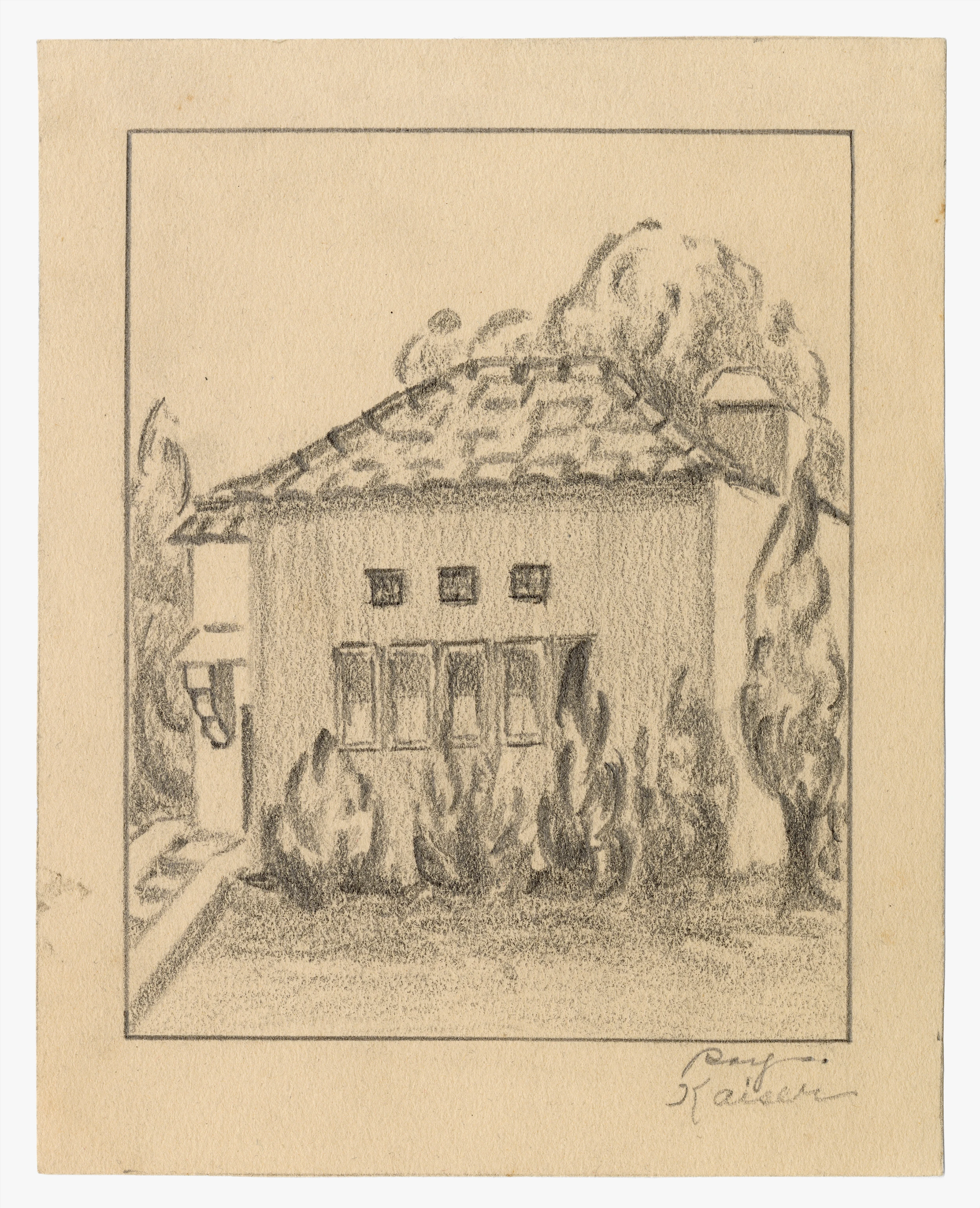

In Mexico, Charles learned that he could get by with little money, and resolved from this point forward to only work on those things he found interesting and enjoyed, rather than for income. He was also struck by the satisfaction derived from collective enterprise—people working in service of families, communities, and the church. It was a humanistic ethos he carried with him when he returned to the US the following year and formed a new architectural enterprise with Robert Walsh. Together, Eames and Walsh designed two Catholic churches in Arkansas for which they created every element, including fixtures, stained glass, furniture, and textiles. By virtue of either an Architectural League of New York exhibit or the local press, Charles’s work—including six residences in the St. Louis area—came to the attention of the famed Finnish-American architect, Eliel Saarinen. Charles consulted informally with Saarinen—who, in addition to leading his practice, headed the Cranbrook Academy of Art—on the design for his next commission, the 1937 Meyer house. The modern-leaning design shows signs of Saarinen’s increased influence (Charles even went as far as to commission textiles by Saarinen’s wife, Loja, for the home). The offer of a fellowship followed and in 1938 Charles joined Saarinen at Cranbrook.

Early Ray

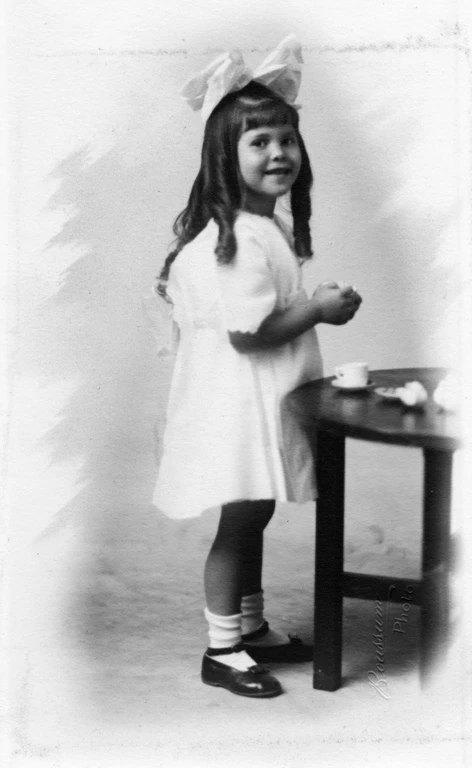

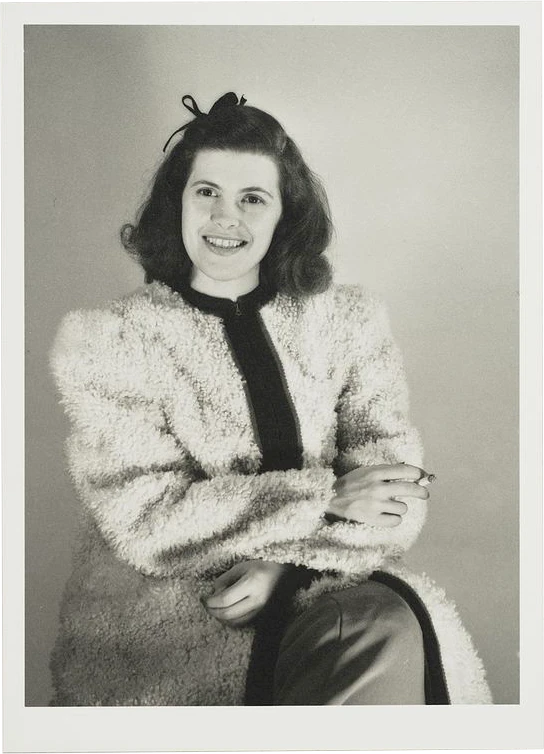

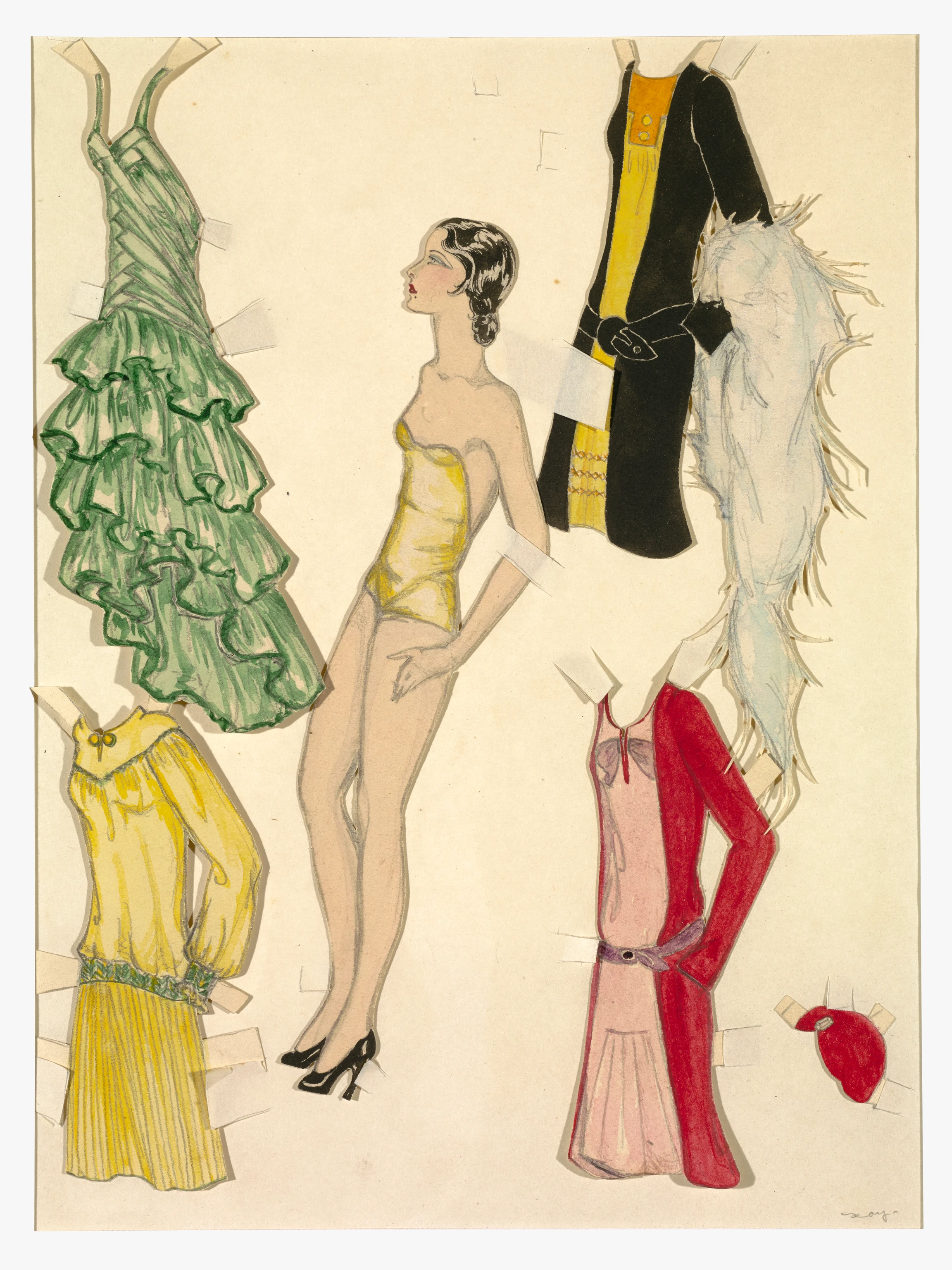

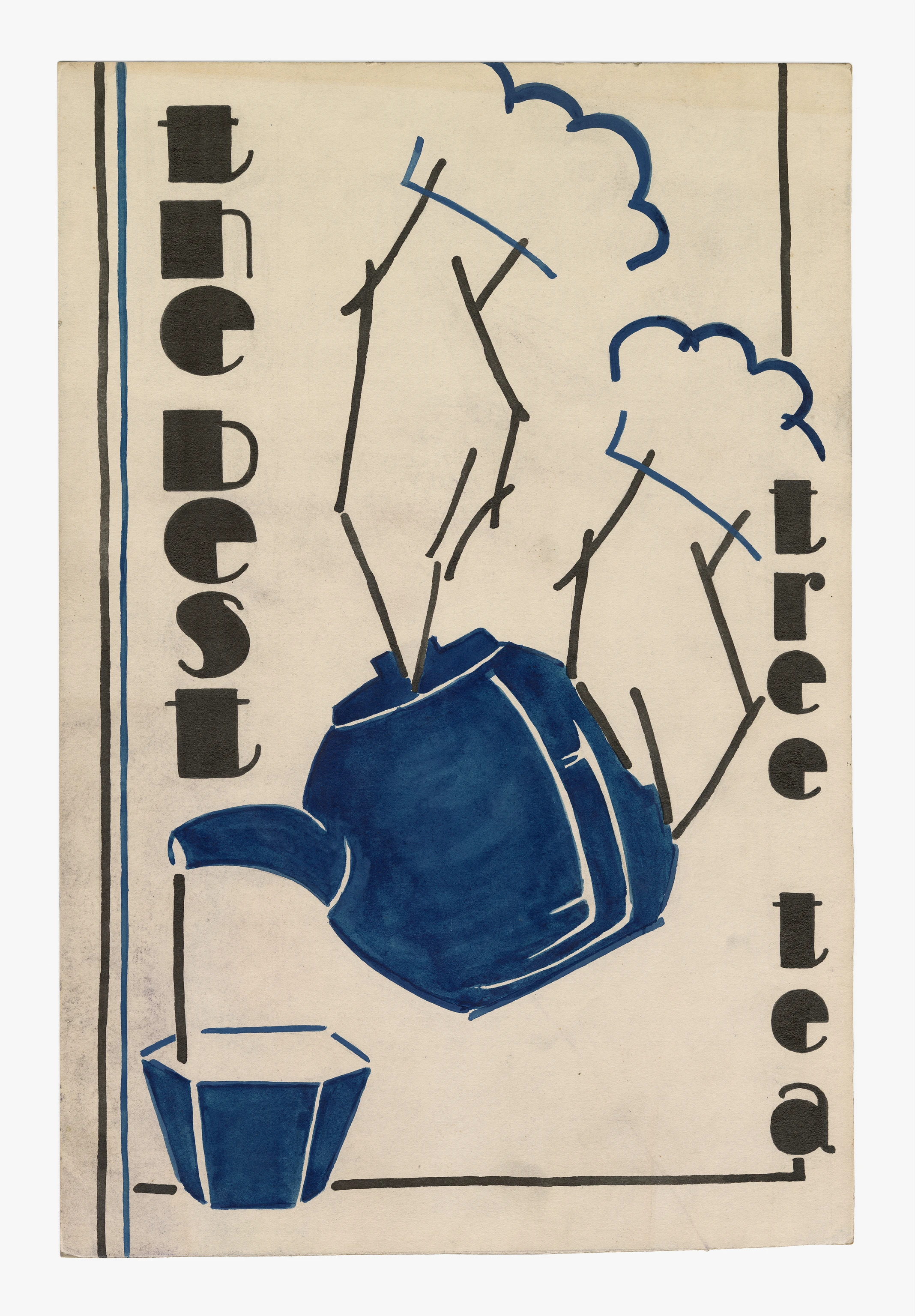

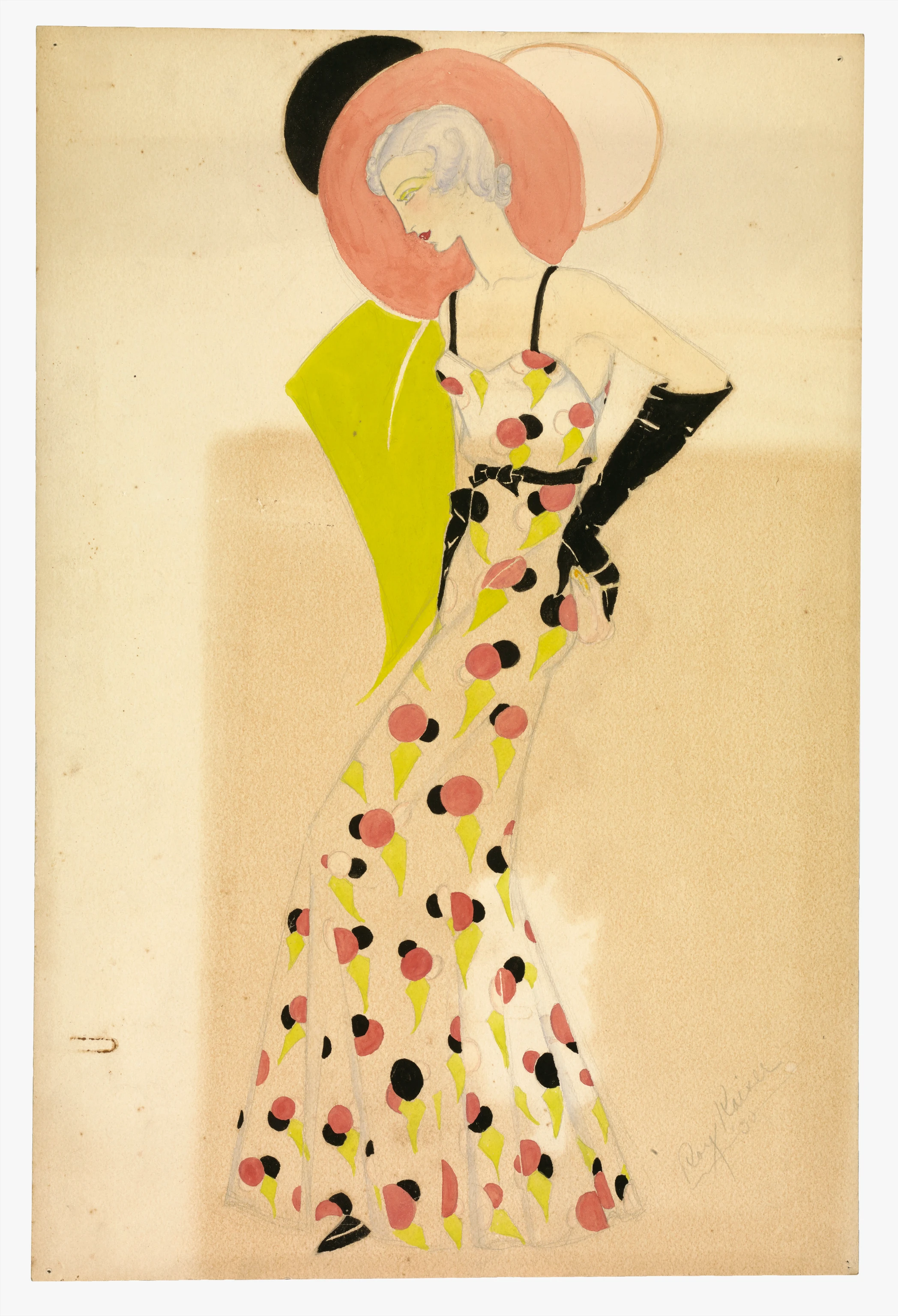

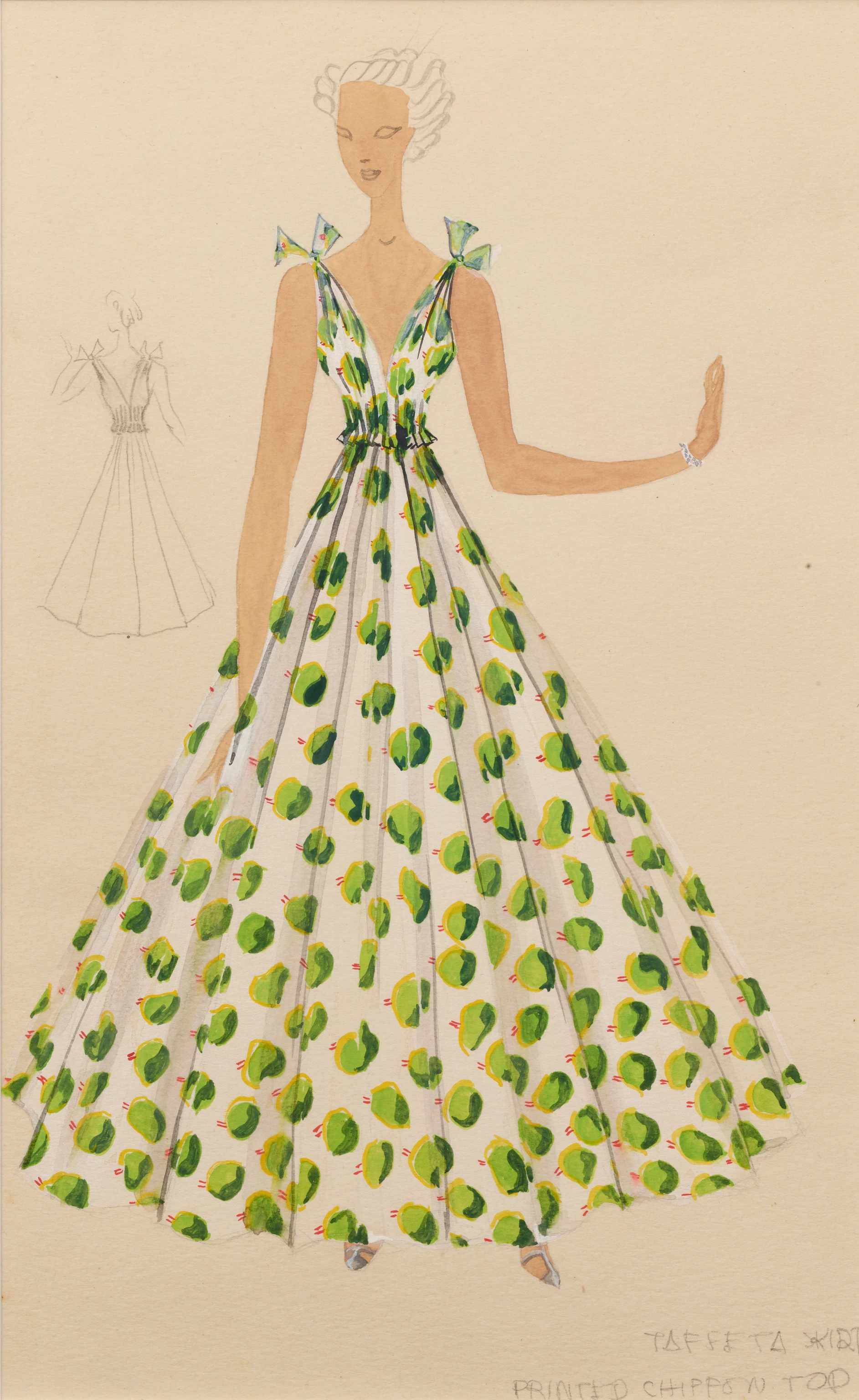

Born in Sacramento, California, in 1912, Bernice Alexandra Kaiser’s earliest years were shadowed by the untimely death of her elder sister, Elizabeth, within months of her birth. Perhaps as a result of the tragedy, “Ray-Ray” (as she was called informally) grew up in a tightly-knit environment with her protective parents and brother Maurice. Her father, Alexander Kaiser, ran a variety theater in the Bay Area that hosted vaudeville acts and her early interests reflect an extension of what she likely saw there: dancing, costumes, colorful scenography, and stagecraft. As a schoolgirl, she designed paper dolls with a range of fashionable and practical outfits that could be swapped out and affixed with paper tabs, and she made colorful sketches of her own clothing ideas. Always pragmatic, Ray announced her intention to pursue a career in commercial art, either in fashion or in advertising. She also developed a lifelong signature look: hair pinned into an updo with a bow, tailored shirts, neatly cropped jackets, and dirndl skirts that conveyed a whimsical but humble aesthetic.

When her father died, Ray and her mother moved to New York to remain close to her brother, Maurice, who was enrolled at West Point Academy. In 1931, Ray attended the May Friend Bennett School in Millbrook, New York, and her art tutor, the sculptor Lu Duble (Lucinda Davies) steered her promising young pupil to the studio art classes of German abstract painter Hans Hofmann. At the Art Student League in New York City, Ray studied Hofmann’s “push and pull” theory of art, which demanded visual work deploy a tension between color, form, and space in order to bring it to life. (Ray held lifelong friendships with fellow students Lee Krasner and Mercedes Matter. Two Hofmann paintings maintained pride of place hanging from the living room ceiling of the house she later built with Charles.)

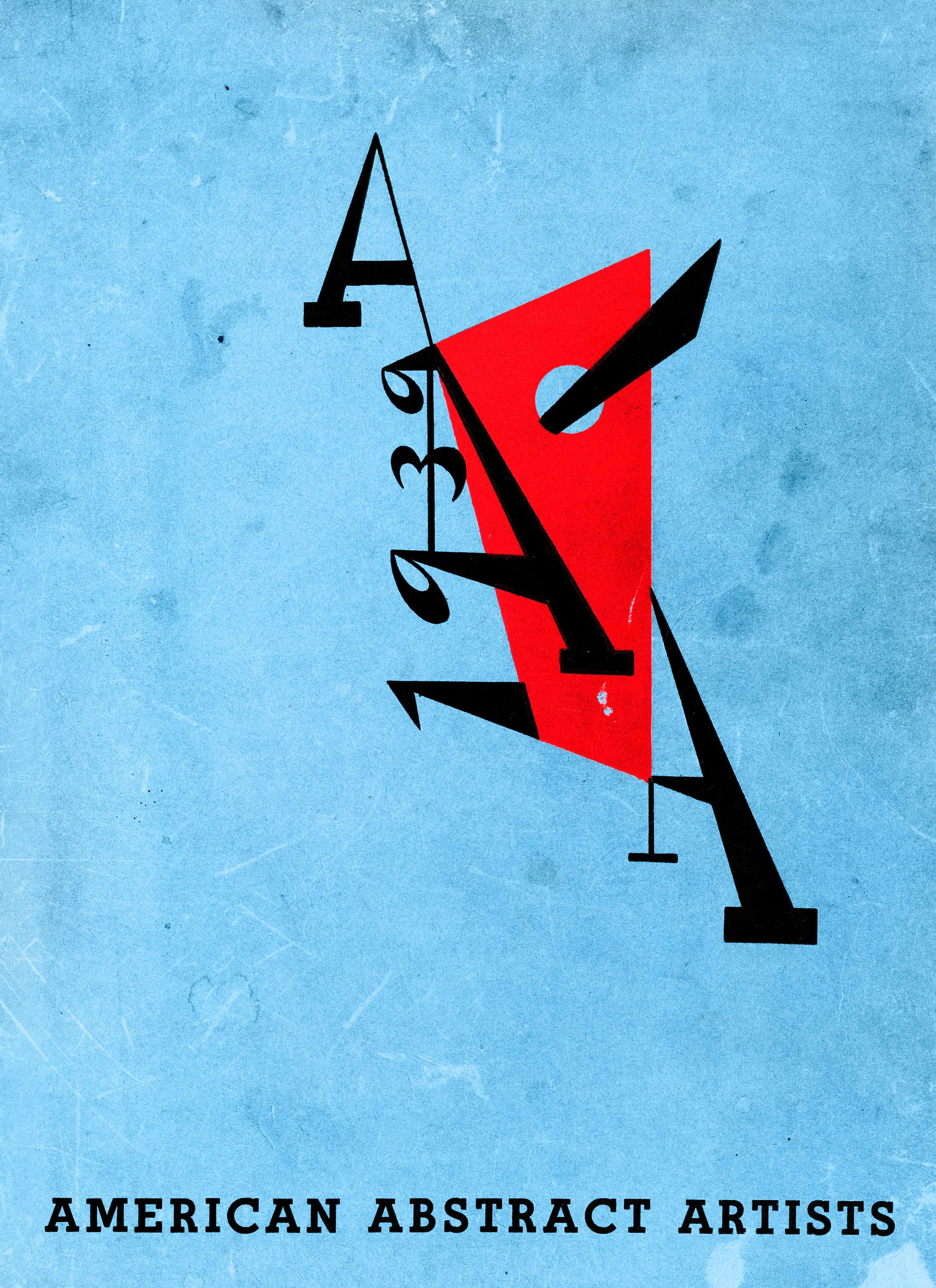

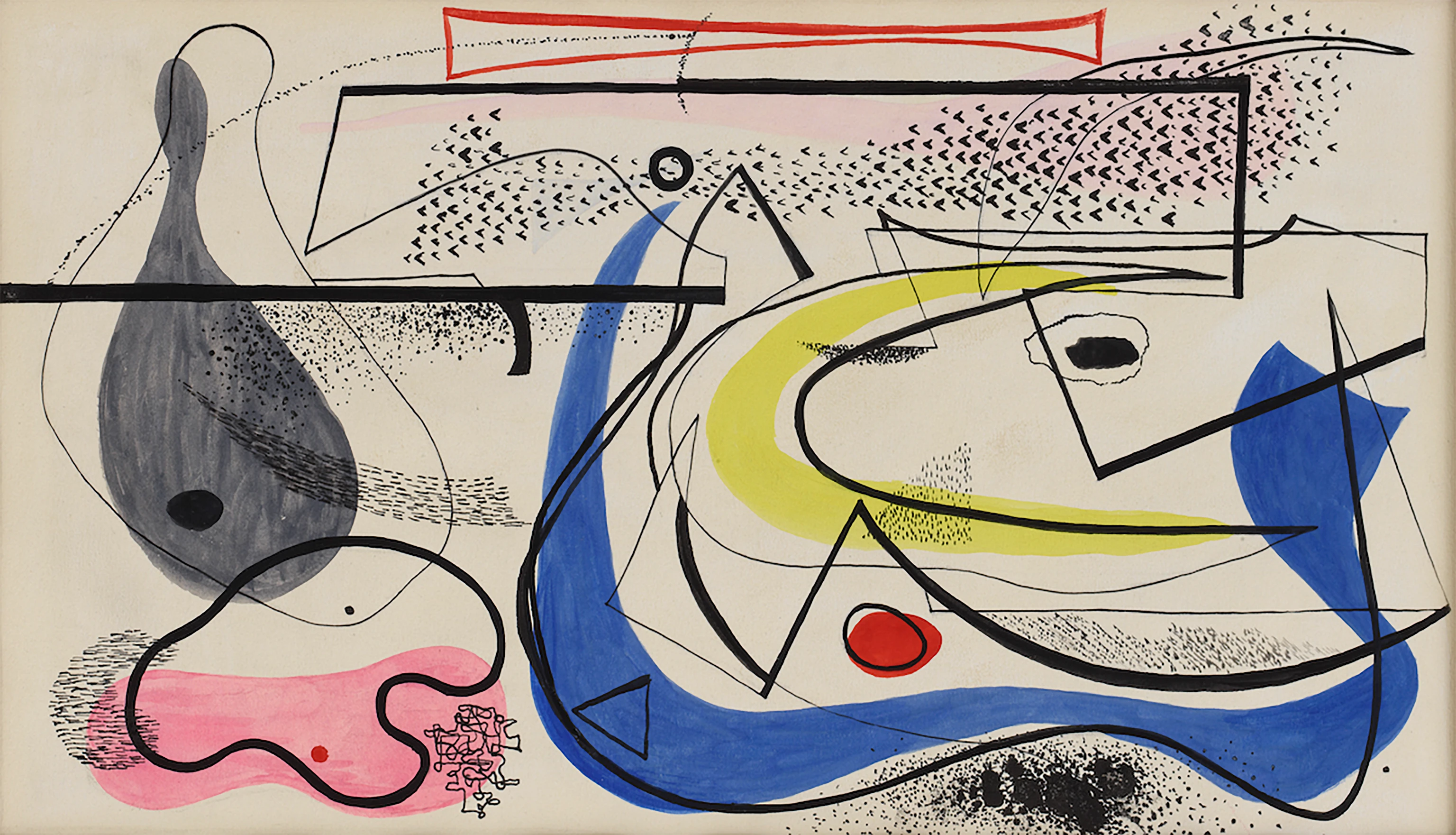

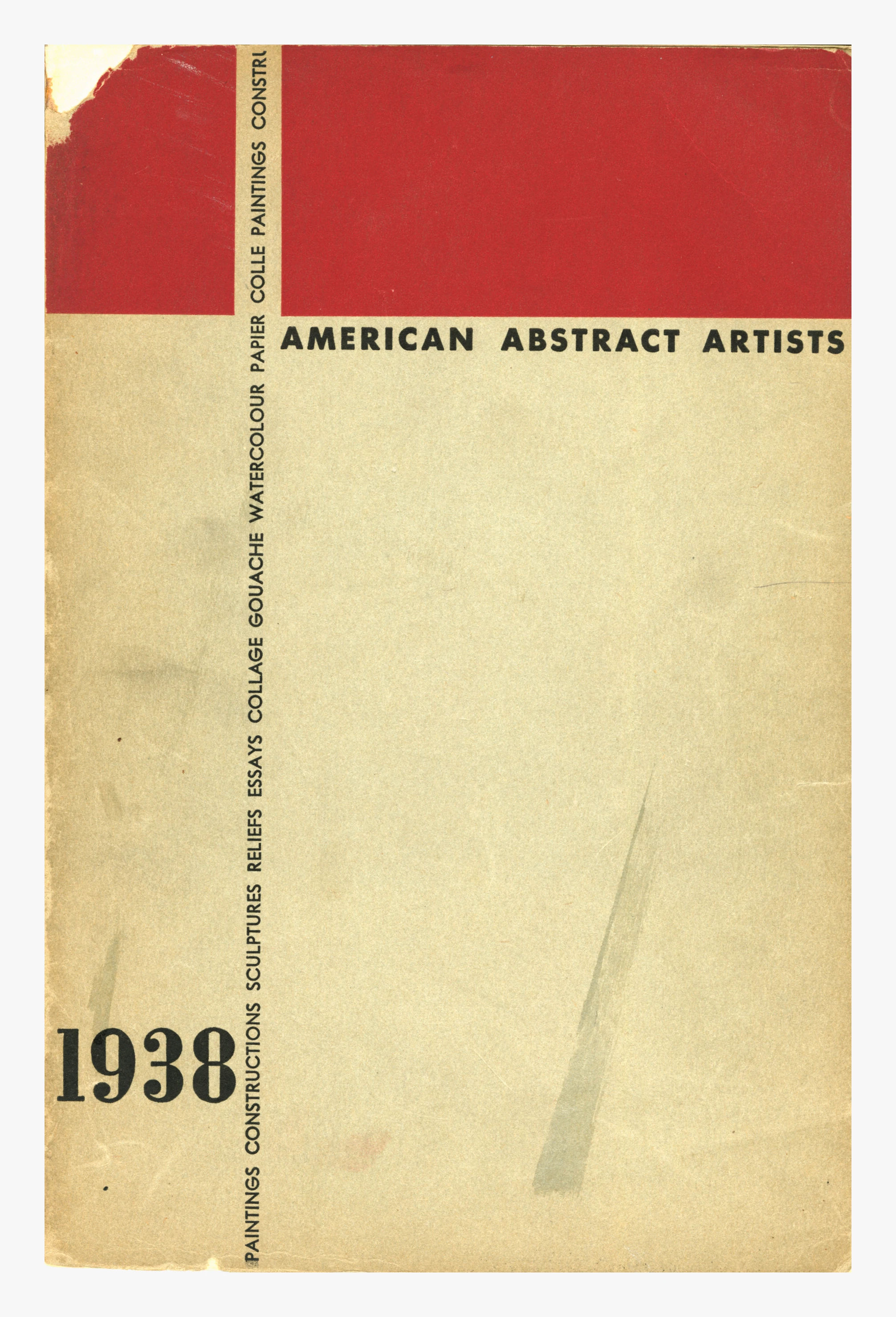

For most of the 1930s, Ray devoted herself to her abstract work, and her artistic subjects evolved from figurative and still life imagery to abstract constructions that generated spatial momentum and employed vivid patches of color. Ray became a founding member of the AAA (American Abstract Artists) to support modern art when museums and galleries refused to display it, participated in AAA’s inaugural exhibition in 1937, and was published in their subsequent catalogs for 1938 and 1939. She would later write, “My interest in painting is the rediscovery of form through movement and balance and depth and light—using this medium to recreate, in a satisfying order, my experiences of this world with a desire to increase our pleasure, expand our perceptions, enrich our lives.”

Untitled, Ray Kaiser, 1937

View the artifact

After her mother’s death in 1940, Ray considered returning to California, but former Hofmann associate Benjamin Baldwin suggested she might join him at Cranbrook, where she would benefit from the holistic approach to art being practiced there. In September of 1940, she began auditing weaving classes with instructor Marianne Strengell, and would soon assist in developing Charles and Eero Saarinen’s entry for MoMA’s Organic Design in Home Furnishings competition. The rest, as they say, is history.