The history of the Eames Aluminum Group is a story of targeted problem solving paired with unforeseen adaptation. The furniture collection, defined by its innovative combination of metal and textile, was transformed over time both in design and in use, migrating first from outdoors to indoors, and then from home to office.

The project was catalyzed in 1957 by remarks made by designer Alexander Girard, a friend of the Eameses, while he was working with architect Eero Saarinen, and landscape architect Dan Kiley, on the Columbus, Indiana, Miller House for industrialist J. Irwin Miller and his wife, Xenia Miller. Girard, who was responsible for the home’s interior design and furnishings, found himself without modern outdoor furniture options suitable to the architecture. He conveyed this problem to the Eameses, who then took the particular problem of the Miller House and generalized it to the broader question of how to create modern outdoor furniture that would be both durable and comfortable.

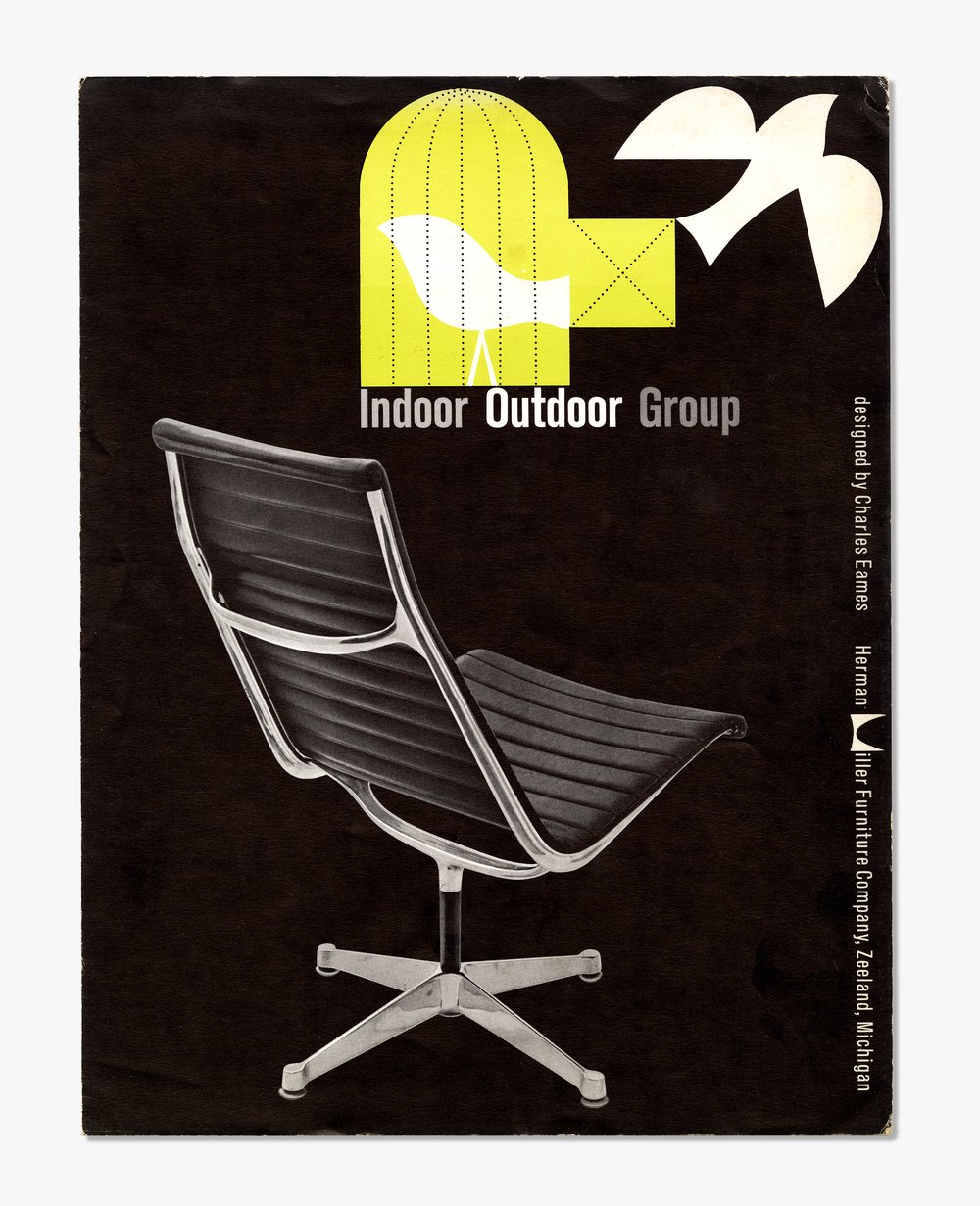

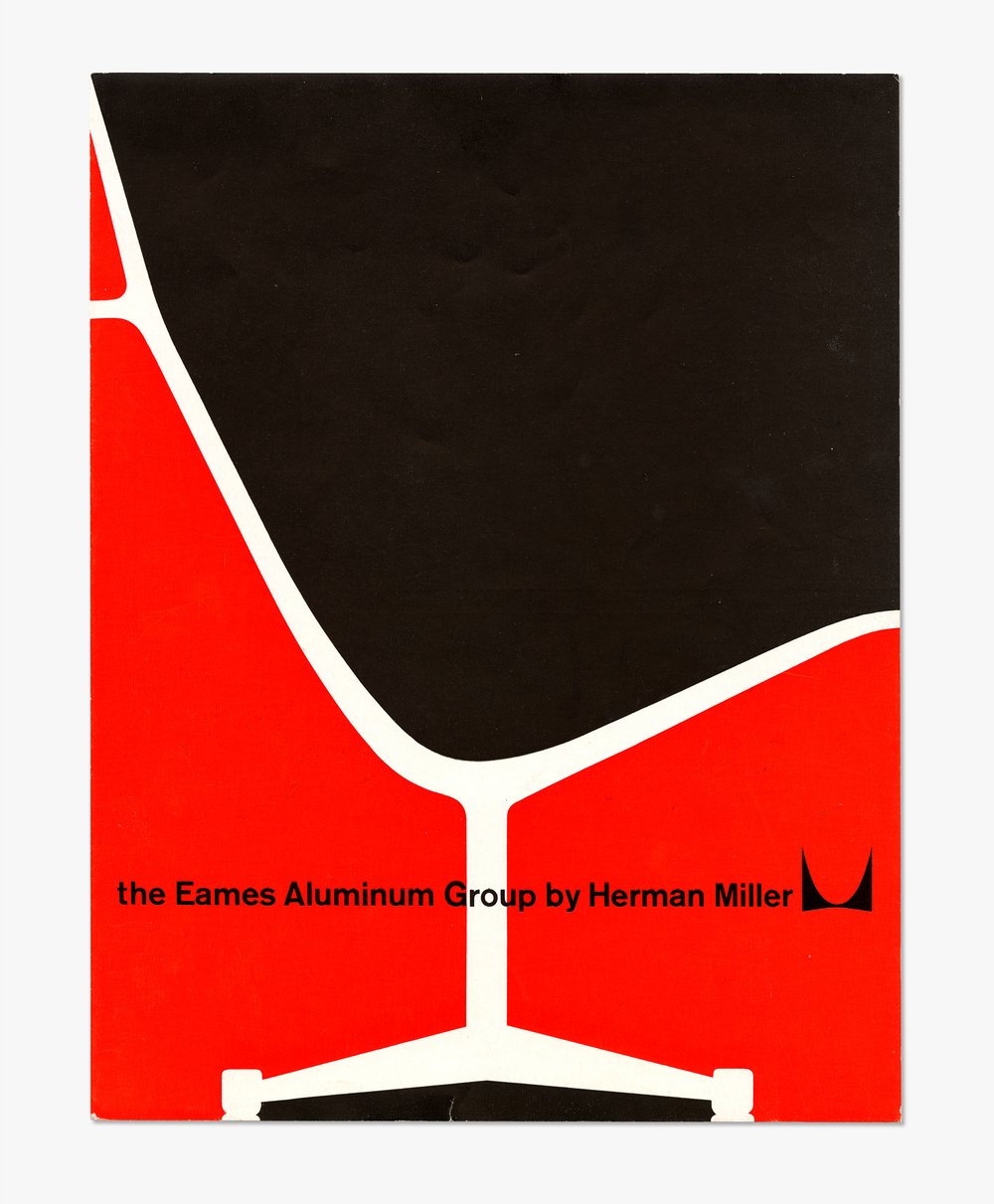

The framing of the initial task explains why the Eames Aluminum Group was called the “indoor-outdoor group” and “leisure group” during its development and early promotion by Michigan-based manufacturer Herman Miller. (Today Herman Miller and Vitra are the exclusive distributors of Eames-designed furniture). Together, these names allude to a significant trend of the postwar period: the increasing value placed on leisure activities—especially those that took place outdoors. In particular, the suburban backyard became an important site of entertainment and relaxation, and thus a new frontier for modern design.

The materials that define the collection, aluminum and synthetic fabric, were chosen by Ray and Charles for their qualities of strength, lightness, and durability, and are emblematic of developments in material resources and technologies that shaped U.S. postwar design. The demands of war led to increased aluminum production, and in the same period much effort was directed toward creating new synthetics that could replace traditional materials. When the war ended, designers were free to experiment with consumer applications for these newly available resources.

In this, the Eameses were ahead of the pack. By the time they sought to create a new system of furniture for use in multiple settings and environmental conditions, they had already developed groundbreaking production techniques and technologies for their molded plywood, wire, and plastic chairs. With the earlier designs there was some concern for producing designs that could weather the elements (despite the fact that they were often photographed outdoors in the moderate Los Angeles weather), but it was the Eames Aluminum Group that first prioritized this goal and represented a significant shift away from the painted steel and wrought iron outdoor furniture that was popular at the time.

The collection’s development began, according to Charles, with a cross-sectional sketch akin to an architectural section. This drawing captured the fundamental idea of the design, which Charles described in Interiors magazine as “a system of connections based on tensions which served to support the body.” From their earlier experiences, Ray and Charles knew that complicated connections were not only expensive to manufacture but also the points on a design most prone to failure. With the Eames Aluminum Group, the designers were able to do away with glues and screws by creating a molded channel through which the textile sling is slotted and then inversed to create continuous connection and tension along the entire length of the seat. These techniques also yielded an elegant and purposeful design that supports the human body comfortably without springs or heavy padding.

The collection’s aluminum elements were produced by sand casting, a process so unbounded that Charles likened it to artwork and, moreover, to the thrilling terror of the sublime. He claimed that with casting, “you find yourself face to face with sculpture, and it can scare the pants off of you.” But fear did not deter the Eameses from working with aluminum, and they had long had the metal in mind as a material to help meet their aims for modern furniture: user-friendly functionality, affordability, and eye appeal. In fact, the prize-winning chair designs Charles and Saarinen submitted to the Museum of Modern Art’s 1940 Organic Design in Home Furnishings competition specified aluminum legs, though wartime limitations forced them to use wood instead.

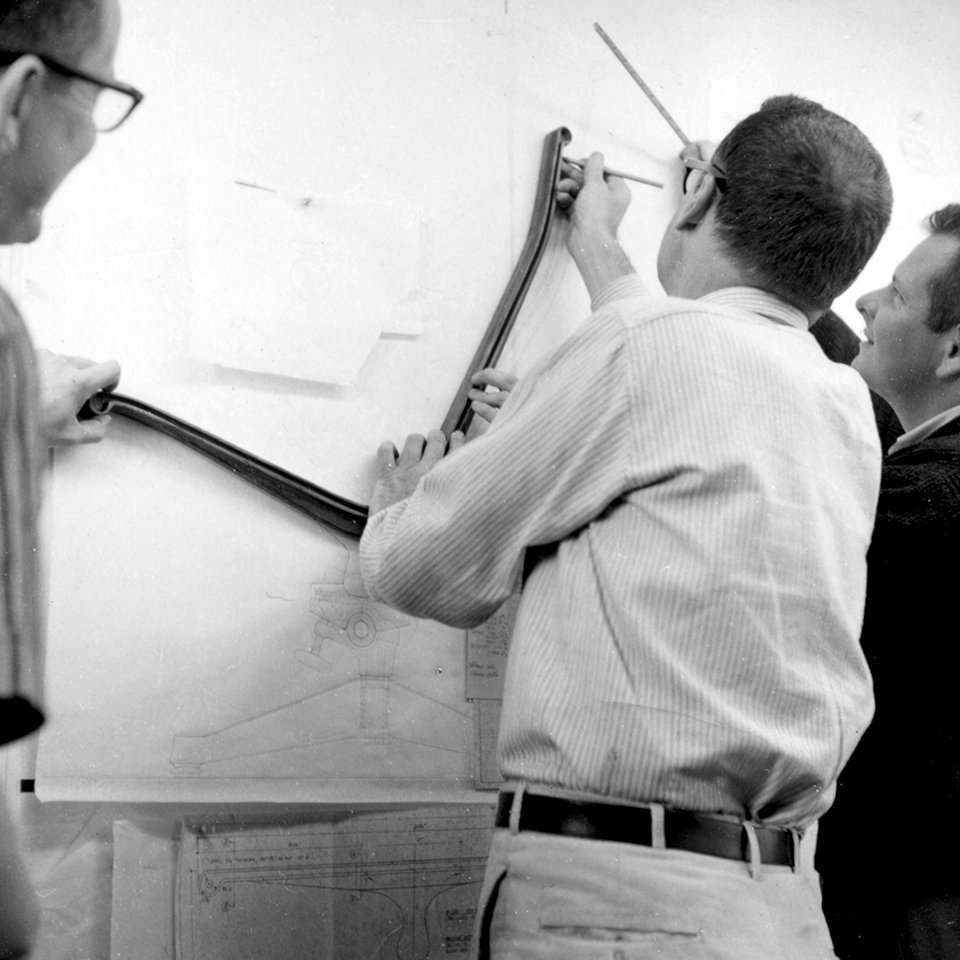

Aluminum finally came to play a starring role in the Eames Aluminum Group, which sped from concept to production within a year. This was thanks to the work of the Eames Office staff, especially Robert Staples and Don Albinson, who worked in the office from 1947 to 1959 and “really fought this one out,” according to Charles. Albinson shares the credit (along with Charles) in the utility patents that were granted for the collection’s mechanical innovations.

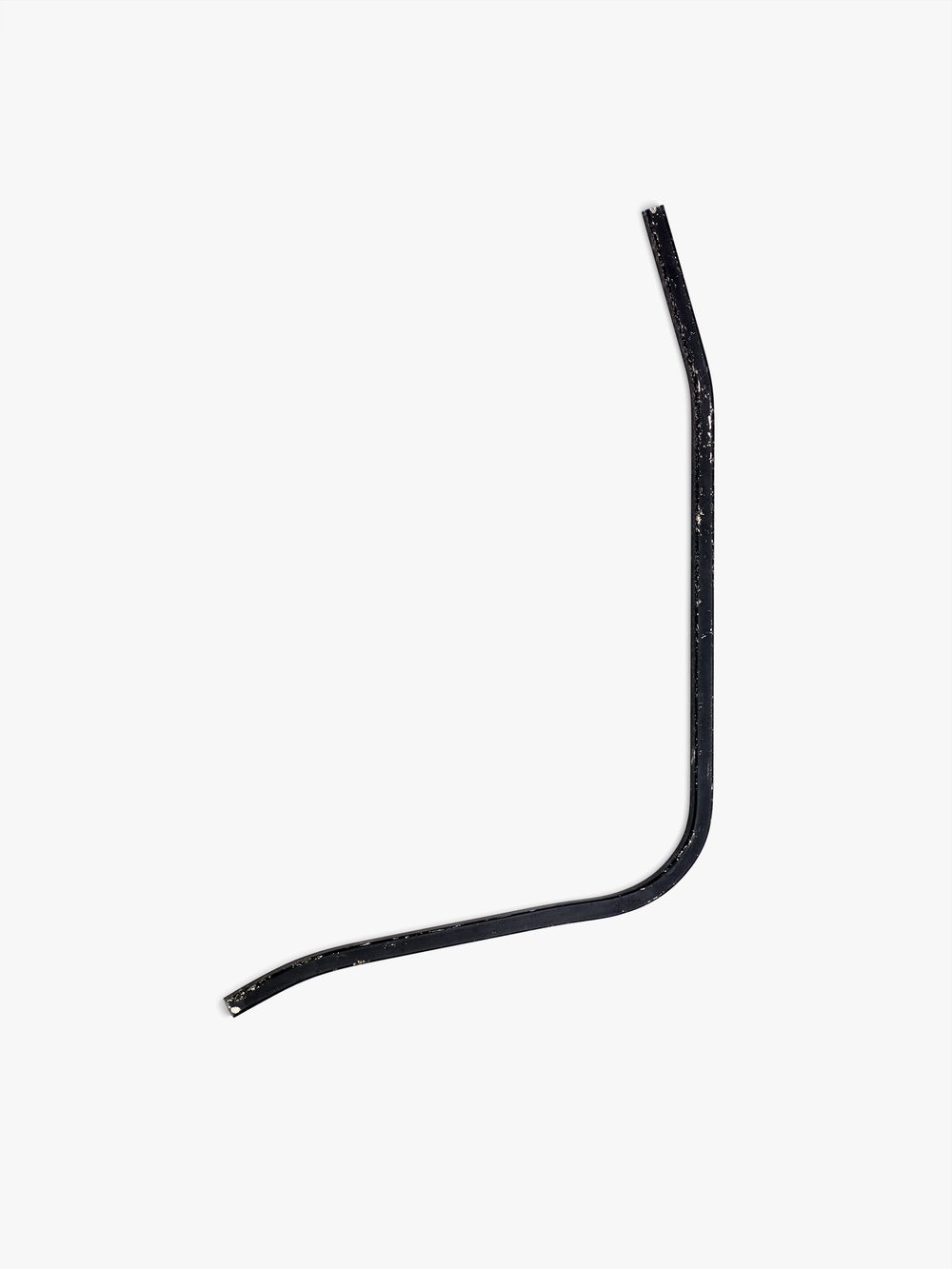

A key structural element of the chairs’ design was the two aluminum stretcher bars that attach below the seat and halfway up its back to hold the side rails taut, and thus create the surface of the seat. When it came to developing these distinctively-shaped stretchers, dubbed “antlers” by the Eames staff, numerous prototypes were produced in wood before their final form was determined. The approach was more scientific than artistic, though eye appeal could hardly be disregarded given how visible they are in the assembled chairs.

The other key aspect of the design—the continuous fabric seat and back— also required experimentation. The design called for a fabric that could withstand great tension, and initially, the chairs were produced with a choice of two synthetic textiles. One was a Saran—lightweight, weather-repellent, and stain-resistant, but ultimately too weak. The other was Naugahyde, a rubber-based synthetic textile that was similarly easy to clean but far stronger. Even so, initial efforts were plagued by sagging fabric, and the design only became viable through the addition of supportive stiffening panels of Fiberthin hidden within the two layers of Naugahyde. The Fiberthin padding was secured by heat seals placed every 1⅞ inches apart to prevent bunching.

The practical success of the heavier Naugahyde may partially explain why the collection—though wildly successful overall—never took off as outdoor furniture. Within a year of its introduction Herman Miller shifted the collection’s marketing away from outdoor use, swapping the name “Indoor-Outdoor Group” for the now-familiar moniker “Eames Aluminum Group” and adding options for upholstery and headrests.

Dale Bauer, Charles Eames, and Don Albinson trace the outline of a side member for a 1:1 scale drawing. Image © Eames Office, LLC

Don Albinson, Ray Eames, and Charles Eames work on upholstery details. Image © Eames Office, LLC

Though the pieces did not become backyard staples, it was not long before another venue emerged. Weighing in at less than 20 pounds, the Eames Aluminum Group armchairs were practically featherweight compared to other office chairs on the market. The Eameses’ commitment to lightweight furniture can be understood as part of a cultural turn toward ease in this period, evident in the rising importance of leisure time but also transformative in the office. At work, however, ease was ultimately in service of productivity. The Eameses’ designs can therefore be understood as an early move toward the kind of flexible, mobile furnishings that overtook office design beginning in the 1960s.

The Eames Aluminum Group, then, represents a compelling point of intersection between several currents that profoundly shaped the mid-century United States: the modernist concern for function and efficiency; innovation in materials and manufacturing; and transforming notions of leisure and productivity. ❤

—Essay by Hannah Rachel Pivo

—Photography by Pippa Drummond

—Styling by Natasha Felker

Explore All Artifacts

Dive into the exhibition—item by item. Clicking on an entry takes you to an artifact detail page containing pertinent details, more images, and in the case of some objects, curatorial notes.